by Albert Steg

While the invention of doubling is widely credited with transforming backgammon into the thrillingly competitive game it is today, the multi-player “chouette” version of backgammon introduced at the same time as doubling in the 1920’s was also central to the game’s surging popularity during the boom that peaked in 1930-31 in the United States. Chouettes continue to be popular among highly committed and competitive backgammon players, but are virtually unheard of among the general backgammon-playing public. That’s a pity, as a chouette is backgammon in its most social form and deserves a place alongside gin rummy and other popular multi-handed games commonly played in the home. It’s also a wonderful game for social mixing in cafes and taverns. If we hope for live, in-person backgammon to boom again, we should encourage chouette play among family and friends in addition to our more formal tournament events.

This page is best viewed on a wide browser screen.

The Essential Chouette

To determine the order at start of play, everyone rolls dice. The high roller starts out “in the Box,” second highest is Captain, and then all further players are ranked 3rd, 4th etc. in line.

“The Box” plays alone against all the rest of the players as a team, who are represented by their Captain. If the Captain loses, the next teammate in line takes their place as Captain for the next game. The player in the Box remains their game after game, until they lose, at which point the victorious Captain becomes the Box. The losing player goes to the end of the line of team players and waits for another chance to play in the Captain’s chair.

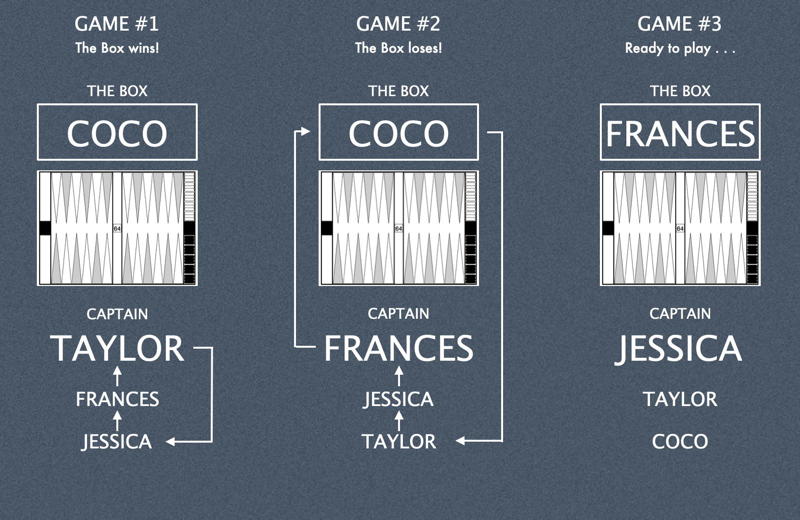

This simple rotation of winning and losing players is the essence of chouette. There can be many variations in doubling rules, scoring, consultation between captain and team-mates, and other subtleties of play, but all chouettes are based on this fundamental pattern of play. The diagram below illustrates a sequence of three games, with arrows charting the rotation of players after the Box wins or loses a game:

A few things to notice:

- The Box may remain unchanged for many games. Lucky winning streaks where one player enjoys win after win as the other players take turns trying to unseat the Box is part of the fun.

- Every game has a new Captain, so you always have a fresh pairing of players rolling the dice.

- The diagram illustrates the sequence, not the physical movement of players. In practice, the loser (whether Box or Captain) stands up and the new Captain sits in the empty chair. So the Box is not always sitting on the same side of the table. The winning Captain simply stays put and earns the title of Box. (Of course, if you wanted to have the Box sit in a fancy chair, or in an actual box, you could do that — but it would just require more moving around.)

- The process is the same for any number of players — a fifth or sixth player would simply extend the list of names at the bottom.

Keeping Score

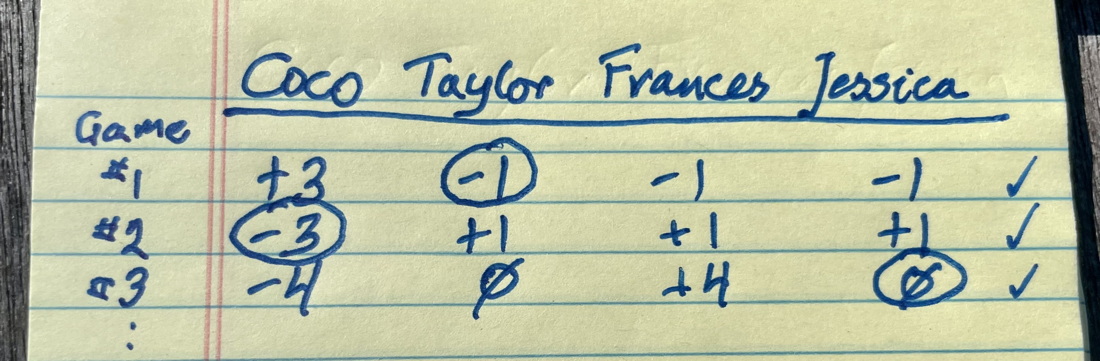

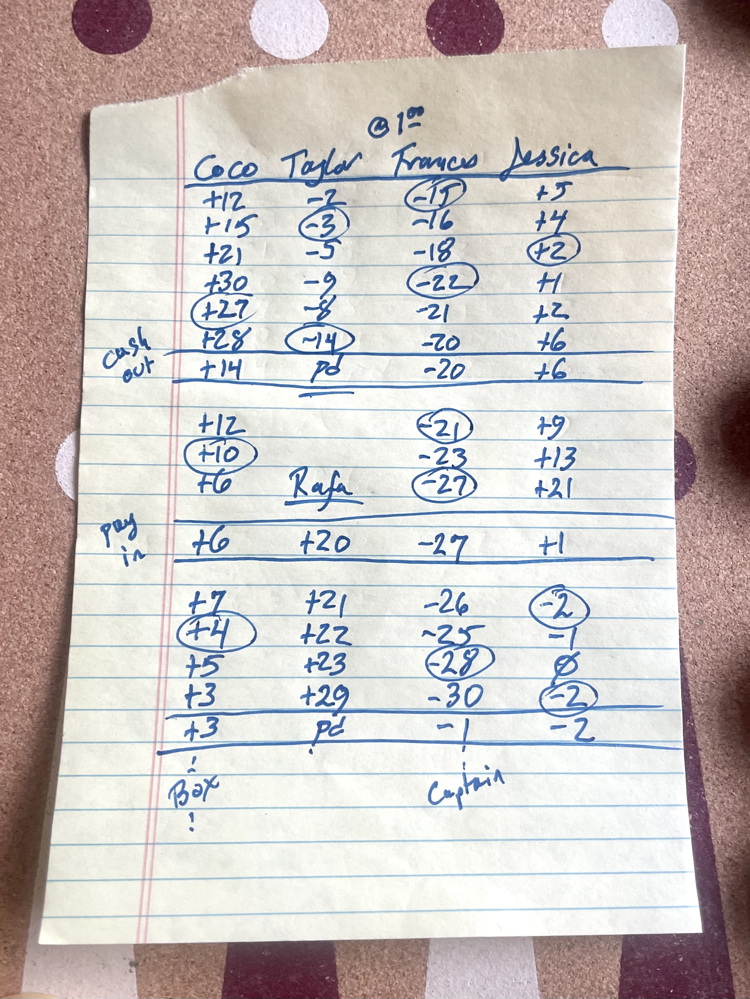

Chouettes are typically played with doubling cubes, but for the sake of simplicity let’s cover scoring without them, but allowing that gammons count for double (2 pts) as usual. To keep score, write the names of the players across the top of the page. After each game, you will simply note the results on a single row, keeping a running total for each player:

Let’s say that in the chouette sequence depicted above, Coco’s victory in Game #1 in the Box was a single game. Since she had three opponents, she earned one point from each for a total of +3, reflected on the first line of the scoresheet along with -1 for each of the teammates. Then Frances gets lucky and wins a gammon as Captain, so each member of the team earns 2 points while Coco loses 6. Frances’ luck holds in Game #3 and he wins a single game, boosting his score 3 points to +4. Now despite her good start, Coco is at -4 while Taylor and Jessica are back where they started at 0.

A few things to notice:

- For every point won, there is a point lost, so each row must add up to zero. The scorekeeper might use a checkmark to confirm the total.

- One way to keep track of the playing order is to circle the loser’s score. So the circles indicate the last time a player got to sit in the Box or Captain’s chair. Glancing at the circles, you can see Taylor is the player who stood up longest ago, so Taylor will be captain in Game #4.

- The games are numbered here simply for reference – it is not necessary to do so.

Maintaining Order

Gardening stakes or popsicle sticks and a sharpie make for an instant chouette ladder.

While circling the loser may suffice for keeping the order straight in a 4 or 5-handed chouette, keeping a ladder of succession to the side of the board is a great way to make it easy for all to see who’s up next, particularly if you have 6+ players, some of whom might want to be “taking partners” in the box (see farther down the page). It’s also ideal for a tournament situation where players may be dropping in and out of the game over the course of a long, rolling session. And a ladder is indispensable if you’re managing an “interlocking chouette” (see also below).

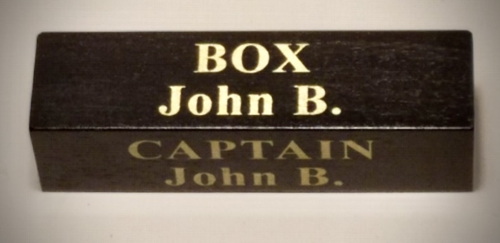

“Shue” block by John Barnett.

Strips of paper will do, but any variety of popsicle sticks, gardening stakes, or plastic name tag holders can be pressed into service to protect against breezes. Michael and April Mesich up in Minnesota like to use spare Jenga blocks, whose 4 sides can be use to indicate whether a player is currently Captain, Box, or Partner! For an added touch of class, you can even order custom inscribed “Shue” blocks in walnut or ebony from John Barnett on his Backgammon Plus+ website.

Simple Starter Rules

Here’s a short set of rules that can get your chouette up and running with the minimum of fuss. As you gain experience, you can explore some of the other rules and variations below that might make your chouette more interesting and enjoyable.

- The seated player who wins is Box in the next game. Loser goes to the end of the line.

- Teammates may freely discuss moves and doubles.

- No automatic doubles.

- The Box must make all available initial doubles or all available redoubles at the same time (all opponents treated the same).

- Teammates may double independently and take independently, and may announce their decision in any order.

- When all teammates initially double the Box at the same time, the Box must accept at least half the cubes. Any passes go in order to players at the end of the line.

If you join an established chouette in your area, you should adapt to their traditions, which will almost certainly vary substantially from this starter set.

Variations in Chouette Rules & Traditions

The basic chouette rotation and score-keeping practices are about the only features of the game common to backgammon players everywhere. Everything else that follows is up for debate and can vary from one circle of players to the next. Unsurprisingly, everyone seems to agree that their own version of chouette is the best, fairest, and most exciting and that rival conventions are unfair or unsporting or tedious. But the truth is that certain rules can be crucial or superfluous depending on the personalities and relative strengths of the participants. Someone may argue “In Chicago we play with Rule X to prevent people from doing Y” – while a Boston player might reply “Well, no one in our chouette does Y, so we find Rule X a pointless nuisance.”

All that matters is that everyone in a chouette understand their own rules and follow them. And when you’re a guest in someone else’s regular chouette, follow the “When in Rome…” maxim and don’t complain too much if you want to be invited back.

The Jacoby Rule

The Jacoby Rule emerged in the 1970’s, proposed by legendary bridge and backgammon expert Oswald “Ozzie” Jacoby and now universally accepted in competitive backgammon circles. The Jacoby Rule holds that gammons and backgammons can only be earned in games when a double has been offered and accepted in the course of play. This rule applies only to open-ended “unlimited” or “money” play sessions like chouettes, and not to “Match Play” competition, where players compete to reach a set number of points (7-point match etc.), as is common in online and tournament play.

The rationale behind the rule is supposedly that it speeds up the action and eliminates some of the less interesting games where one player enjoys a tremendously lucky exchange and becomes an overwhelming favorite, playing out what can be a lengthy and uneventful game just to harvest one measly extra point. But another motivation behind the rule is surely that it is to the advantage of more experienced players who are more adept at anticipating “gammonish” positions — and Ozzie Jacoby was certainly one or those! But given the substantial luck element inherent in backgammon, a rule that rewards superior understanding of the game seems reasonable.

The Jacoby Rule has its critics, but for better or worse, the rule is now widely accepted, and does introduce an interesting added dimension to cube decisions as one weighs the value of “activating gammons.”

Playing for $ Stakes

Although a backgammon chouette can be played purely “for fun,” most players find the game more exciting if some meaning is attached to the points on the scoresheet, and playing for a modest money stake is the traditional way to “make it interesting.” This is especially true if you wish to use the doubling cube, as you should. There can be enormous drama and excitement in backgammon over doubling decisions, just as in the raising and calling actions of poker, and if there is no consequence for making poor decisions or in experiencing incredible reversals of fortune, the contest loses most of its tension. Even a ‘token’ value of a penny per point (as in penny-ante poker) can be enough to provide palpable meaning to the score of a social chouette.

Although a backgammon chouette can be played purely “for fun,” most players find the game more exciting if some meaning is attached to the points on the scoresheet, and playing for a modest money stake is the traditional way to “make it interesting.” This is especially true if you wish to use the doubling cube, as you should. There can be enormous drama and excitement in backgammon over doubling decisions, just as in the raising and calling actions of poker, and if there is no consequence for making poor decisions or in experiencing incredible reversals of fortune, the contest loses most of its tension. Even a ‘token’ value of a penny per point (as in penny-ante poker) can be enough to provide palpable meaning to the score of a social chouette.

How many points might a player expect to lose in a few hours of chouette play? Among experienced competitors, even the strongest player in a chouette will have bad days where they seem to lose a big game every time they get in the Box and face 2-5 opponents. A 50-point loss in a session would count as a pretty bad day, but not a terribly unusual one. In chouettes among experienced and disciplined competitors, the vast majority of games end with the cube on 1 or 2, and accepted 4-cubes are not unusual. But 30+ games can go by without ever seeing an 8-cube accepted. During an entire year of weekly play, there might be fewer than a dozen 16-cubes accepted, and anything larger than that may never appear at all.

Perhaps counter-intuitively, it’s less experienced, low-stakes players who are more likely to rack up really big point totals in a chouette. One reason is that they aren’t clear on the value of cube ownership, or the risks of losing gammons, so doubles are offered and accepted too freely. Another reason is that if the money stake is essentially insignificant, players may accept doubles simply in order to “see how the game turns out.” Why pass? “It’s only pennies.” Under these conditions, 16- and even 32-cubes may appear several times in a single day, and scores of +/- 100 and more points will be virtually inevitable. There’s nothing wrong with enjoying this kind of freewheeling action, so long and the stake is low enough that no one gets hurt.

So, there is no general answer to the question “what is an appropriate stake to play for?” It depends on variables ranging from disposable income to chouette size to cube behavior. For those with some experience and a desire to play on a competitive level I’d suggest playing for a stake such that a 50-point loss will be annoying but a 100-point loss will not be distressing. If losing 50 points really doesn’t matter a bit, it may be difficult to take doubling seriously. But on the other hand if losing 100 points causes real distress, then you won’t be comfortable offering or taking all the cubes you should when you are in the Box. If you play in large chouettes of 6+ players or allow “automatic doubles” (see below) you should feel very comfortable losing 100 points in a session.

The key to building a happy chouette is to find a circle of players who are in a similar ballpark of experience and who feel comfortable playing for a similar stake. The stake should merely be a means of making the cube action meaningful and providing a cumulative effect to what would otherwise be just a long series of unrelated games.

On a final note, it is well to note that playing backgammon for “friendly stakes” without anyone gathering any kind of table fees (or “rake”) should typically fall under legal allowances for “social betting,” but both laws and enforcement can vary from state to state and even town to town. NEBC offers no assurance that playing a backgammon chouette for a cash stake is legal in your circumstance. Also, when playing outside your home in a private club, coffee shop, or other public space you should be sensitive that proprietors and other patrons may not feel comfortable seeing cash changing hands over a backgammon board, even if perfectly legal.

Managing Payouts on the Scoresheet

A player who decides to call it a day pays or collects the amount due to or from one or more other players on the scoresheet. It makes sense to pay the player up the most on the scoresheet or collect from the biggest loser, but it doesn’t really matter so long as everyone in the chouette is trustworthy. In the $1 chouette scoresheet at right, we see Taylor paying $14 to Coco on a “cash line” — a line where no game has been played, but the scores have been adjusted to account for a payment.

A player who decides to call it a day pays or collects the amount due to or from one or more other players on the scoresheet. It makes sense to pay the player up the most on the scoresheet or collect from the biggest loser, but it doesn’t really matter so long as everyone in the chouette is trustworthy. In the $1 chouette scoresheet at right, we see Taylor paying $14 to Coco on a “cash line” — a line where no game has been played, but the scores have been adjusted to account for a payment.

The chouette proceeds when a new guy, Rafa, who’s been hovering around the game with a martini in his hand asks if he can play. He seems friendly and knows about the doubling cube but has never played a chouette before. Since no one knows him, Coco is welcoming but asks if he’d be willing to “buy 20 points” on the scoresheet with the understanding he can bow out at any time and be paid for whatever points he has in his column. Rafa agrees, and gives Jessica $20, represented by +20 for him on the second “pay line,” while Jessica’s score is reduced -20 accordingly.

Rafa turns out to be both lucky and quite good at the game, and after 5 games is +29 and needs to go home. Frances graciously pays him $29, the payout is noted on another cash line. Since Rafa was in the Box when he left, the next player in line, Coco (note she has gone the longest without being circled), inherits the box and Frances is the next Captain as play continues.

Rafa turned out to be a regular player in the chouette. Having exchanged contact info, next time the regulars didn’t ask him to pay points up front, but agreed that anyone who went down -20 pts on the scoresheet should pay it off and start fresh. Setting a limit on scoresheet debt can be a good policy when you have a chouette among players just getting acquainted with each other.

"Automatic" Doubles

There is an old tradition popular in some circles to turn the centered cube up to ‘2’ at the start of a game when both players roll the same opening number. The practice has the effect of introducing some artificial volatility into a backgammon session, as it arbitrarily gives some games twice the weight of others. There’s no harm in it so long as everyone is willing, but be aware that an automatic double can put a lot of pressure on the Box. In a 5-handed game where the cubes start on two, if the Box accepts doubles from all four opponents and suffers a gammon, that’s a 32 point loss in a single game. Ouch! (And some chouettes actually allow multiple autos so games can start on 4 or even 8-cubes.)

One popular solution is to allow only the Box to decide whether to impose an automatic double on their opponents, so that no one is forced to hazard such a costly loss in the Box. But it’s never a good practice to impose autos on players who do not welcome them: it can feel like bullying. The friendliest approach is for the Box to merely offer the option “Who wants an auto?” — and allow them only by mutual consent.

Another scenario that sometimes arises is when a player down substantially on the scoresheet asks to start games with the cube on 2 in the hopes of recovering more quickly in the time remaining — and escalating to 4 or even 8-cubes when unsuccessful. This is not behavior typical of the more successful competitors, who focus on winning in the long run and therefore worry less about the result of any single session. Depending on the temperaments of the players, it can be viewed as “sporting” to allow the trailer this chance to make a rapid comeback, but just as often it can lead to unusually heavy losses and bad feelings for both players. So this practice should be indulged with caution.

Consultation Among Teammates

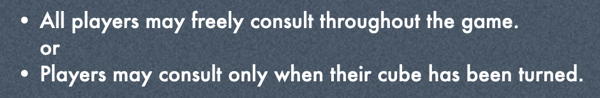

In its original 1930’s form and up into the 1970’s, teammates were free to consult with the Captain on checker plays as well as cube decisions, but originally there appears to have been a general understanding that the Captain should be left to play the game with only occasional help on obvious misplays or oversights. Perhaps owing to the pace of chouettes slowing down due to constant wrangling, and perhaps also to the tendency for checker play to be dominated by the two strongest (or most aggressive) players at the table, rule options barring or restricting consultation came into use sometime in the 70’s and have endured:

“Open Consultation” is a good way for players at any level to pool their knowledge and improve their games together, particularly if they are of a similar skill level and have differing strengths (such players make excellent doubles partners too). However, if a couple of players are the undisputed masters of the group, there can be a tendency for them to dominate play and for the chouette to feel somewhat homogenous, with the other players simply moving checkers as they’re told.

Consultation only after one’s cube has been turned is now the predominant rule. The Captain soldiers on without aid from teammates until they earn talking privileges by having their cube turned (and accepted). Only players still in the game may comment on play. This policy introduces some interesting tactical wrinkles in cube handling. For instance, a teammate might double more aggressively than usual in order to offer assistance to a less experienced Captain, and on the other hand the Box might pass the cube of the strongest player at the table while accepting the others (if the rules allow it) — sometimes playfully referred to as a “non-consultation fee.”

![]()

Since everyone gets to go their own way on cube decisions, there isn’t really a need to allow discussion of them, and almost all chouettes follow this rule, though there are often lively post-mortem discussions when the game has ended.

![]()

Some chouettes allow a general sharing of the pip-count, regardless of other consultation rules. The idea seems to be to speed up the game by helping out slower pip-counters. In practice, your milage may vary. In the worst case, someone or other requests a pip-count several times per game, often when others see little need for one, at which point three or four players begin counting, muttering numbers and pointing to various checkers and getting in each other’s way. Often, the counters come up with conflicting results so they go at it again until a consensus is reached. These days you can always have someone with an Android phone be the designated pip-counter by using the new AI-driven Gammonsnap app, (so long as you trust them not to run an evalution on the cube action or checker play while they’re at it). But while some find public pip-counting merely tedious, many others find it objectionable because they believe counting is a skill like any other in the game (and requiring nothing more complicated than addition and subtraction), so why reward players who can’t be bothered to master it themselves? And of course pip-counting is allowed any time among players eligible to consult.

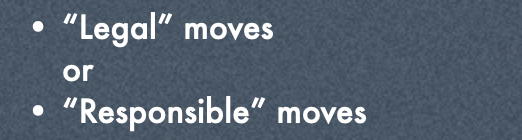

Legal Moves

Backgammon is particularly prone to unintentional mis-plays. Dice can be mis-read, checkers may be played and then re-set incorrectly, blocked points may be overlooked, and moves made inaccurately. There has been an overwhelmingly popular movement toward adopting a “Legal Moves” rule in competitive play whereby any illegal play must be corrected by any players who notice it, whether or not the correction to their advantage.

The alternative rule, “Responsible Moves,” give a player who notices an illegal play the option of having it corrected or allowing it to stand as played, even in the case of clearly inadvertent actions like placing ones own checker on the bar when intending to hit a blot. This practice can lead to particularly bitter feelings when a careless Captain makes a gratuitous blunder that costs teammates a major loss — and can even open the door to a cheating tactic where players in cahoots with each other may “accidentally on purpose” dump teammate equity to a friend in the box and divide the spoils later.

Doubling / Taking Rules

Multiple cubes are a good sign a player enjoys a chouette now and then.

When the chouette was invented in the 1920’s, the Captain made all the doubling decisions for the entire team. There were no “separate cubes” for the simple reason that the cube had not been invented yet! Without a simple marker for the “doubling privilege,” it would have been chaotic for various players to double at different times (betokened by multiple piles of matchsticks on the bar) and for the doubling privilege to rest with the Box against some players, and elsewhere against others. The single-cube tradition held up well into the 1970’s, with various provisions made (some quite unfair) for allowing the Captain to buy out a partner who disagreed with the Captain’s action. But for several decades now, chouettes have been played with multiple cubes so that each player may make their own doubling decisions.

While multiple cubes have eliminated disagreements and settlements between Captain and teammates, they have opened up many variations in doubling protocols. Some of these variations clearly favor the strongest players, and some find them exploitive and therefore objectionable. (They have sometimes been called “fish-hunt rules.”) Others however, find strict protocols rob a chouette of some of its playful dynamics, which involve getting to know various players’ doubling styles and, yes, exploiting their weaknesses. A great deal depends on the participants in a particular chouette — is everyone in the same ballpark of skill? Are the less adept players apt to feel picked on? Does everyone want to get in, and stay in, the Box?

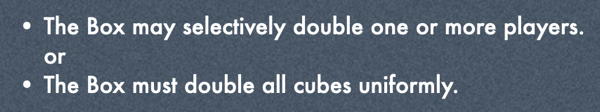

Doubling Protocols

In the single-cube days, when the Box doubled the Captain, all teammates were doubled along with him. With multiple cubes, the Box might often double some players sooner or later than others for a variety of reasons, including the aforementioned “consultation” factor or because some players are known to pass cubes earlier or accept cubes later than others. One objection to selective doubling is that it can lead to bullying tactics where for instance the Box might double only the weakest player in the chouette in a position that is a big pass, hoping for an incorrect Take, and then double out the stronger players on the next turn while the victim suffers through the game alone. This sort of thing was popular in the old Harvard Square days of the 1990’s and viewed as just part of the accepted gamesmanship of chouette play, introducing an element of misdirection and bluffing to the game. But backgammon in the 21st century has evolved into a somewhat more even-handed and generous game.

Another, perhaps even stronger argument against selective doubling is that by doubling only a portion of the field, the Box creates a conflict among the teammates, as checker plays can be highly dependent on cube position. While this can also occur when only a few members of the team double the Box, at least then it is their own doing.

So, many chouette rules insist that the Box must double all cubes together — or at least, all same-state cubes. For instance, if only two members of the team double, leaving two other cubes unturned, the Box might later decide to double the centered cubes but not the ones he already owns. But he would not be allowed to selectively re-double only one of the cubes he owns and not the other.

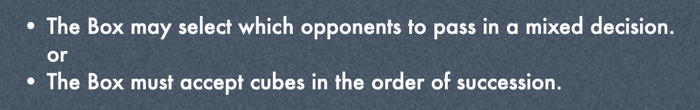

Taking Protocols

![]()

The idea here is to keep at least half of the players involved in the game. Imagine four players doubling the box and the Box accepting only one cube. Three players score 1 point and then sit around waiting for the other two to finish what might be a lengthy game. This rule holds that the Box would have to accept two of the four cubes, so that at least three of the five players are engaged in the current game.

The rule does not apply to re-doubles for the simple reason that they are much less common, and typically occur closer to the end of a game, so not so much time is wasted. Some chouettes allow the Box to take a single initial cube in a non-contact (racing) position for the same reason.

Your rule on this will probably match your rule on doubling selectively, under the same logic. Allowing the Box to choose keeps alive some of the old “game within a game” dynamic of chouette play, in which stronger players, knowing that a particular player in the Box doesn’t like to accept all cubes, will double aggressively, anticipating that the rest of the team may go along, doubling en masse, and that the Box will choose to drop the instigator and take the rest. This can lead to amusing situations where the teammates don’t go along and the instigator gets punished by giving away the cube prematurely. Many chouettes prohibit the Box from passing the Captain while taking others, which can make sense depending upon the rules for succession to the Box (see section further down this page).

The more restrictive rule forestalls situations in which some players feel they are being targeted by the sharks at the table. The players at the end of the line are the ones getting passed, if any.

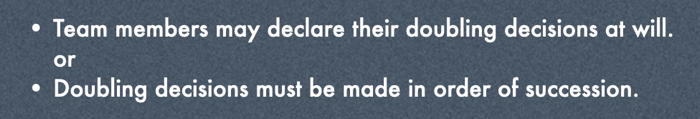

Declaring Doubling Decisions in Order of Sucession

In Boston we take a very casual approach to announcing doubles and takes — people can call it out at will. If less experienced players want to wait and see what the top players in the group do, that’s fine.

Other groups insist that the players on the team declare their cube action in order beginning with the Captain. The strict rule seems fair because it puts everyone in a position where they must decide first, it adds some drama to this aspect of a game, and it increases the skill element (in favor of the Box). But then again some feel that this can place the less experienced players on an uncomfortable hot-seat when they are Captain and everyone stares at them waiting to hear their decision. Another argument against ordered declarations is that it can be very difficult for people not to indicate their decisions through body language or spontaneous remarks or even just picking up the pen to begin scoring points — and of course it would be very easy for players to telegraph signals to their friends through pre-arranged signals. Expecting everyone to put on their poker faces and fall silent every time the Box doubles can seem artificial. Finally, when ordered declaration is applied to doubling, it wastes time to have to poll the entire team anytime someone asks to “hold the dice” to consider a cube — particularly if the team is creeping up on a cube over several rolls.

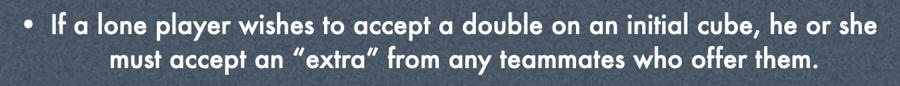

“Extras”

Applicable only to initial cubes in chouettes of 4+ players, this is another measure preventing a majority of players from sitting out a lengthy game — particularly when it is only the Captain wishing to accept a bad double in a bid to get in the Box. A teammate offers to pay the the lone taker one point to accept an “extra” cube in the position. If accepted, the teammate is now rooting for the Box to win, but may not consult on checker plays.

The logic of the “extra” may seem a little difficult at first, but is quite simple. A player who passes a cube thinks that taking it will cost more than one point on average, say 1.12, while a taker believes the position is worth less, say only .93. In essence, they are saying:

Dropper: “I’d rather pay a point than hold a 2-cube in this position!”

Taker: “I’d rather hold a 2-cube in this position than pay a point!”

One point is exchanged for the burden of playing out the position holding a two cube, and both players believe they are receiving something of greater value than they are giving their opponent. That’s what makes it a fair exchange. If the Taker wins the game, the Dropper pays the 2 points on the cube + the 1 point offered in the deal for a total of -3 points. If the Dropper wins, the taker pays the 2 points on the cube minus the 1 point received in the deal for a net of +1 point. This reflects the “25% Rule” of accepting doubles: the taker enjoys 3-to-1 odds by accepting a double. Of course, redoubles or gammons can also affect the final scoring — in any case, the result is adjusted by the one point paid by the Dropper to the Taker. And remember that any extras are in addition to the original cube decision — so a Dropper would have paid one point to the Box by passing, so if the Box wins, the Dropper will neatly “break even” for the game (-1 to the Box, +1 from the extra).

Back in the 1970’s-80’s, there was a very bad rule forcing a lone taker to beaver a cube to play out the game as a deterrent to lone takes. But a lone taker may be correct to accept the double, and forcing them to either give up equity by passing or give up even more equity by beavering is unfair. The “extras” rule allows all players to make the cube decision they believe is right — and gives others the opportunity to profit while maintaining an interest as the game plays out. Win win!

“Softies”

![]()

Local chouette aficionado Matt Reklaitis brings this one back from his European travels to the Nordic Open, where the Danes delight in this wicked twist on cube action. “Softies” is a tongue-in-cheek reference to the earlier-than-usual doubles that get served up in this variant, where the taker winds up holding 4-cubes that have more than the usual potential to be sent back at 8 before the game is through. As you can imagine, the scoresheet can get pretty bloody in this variant, so be careful.

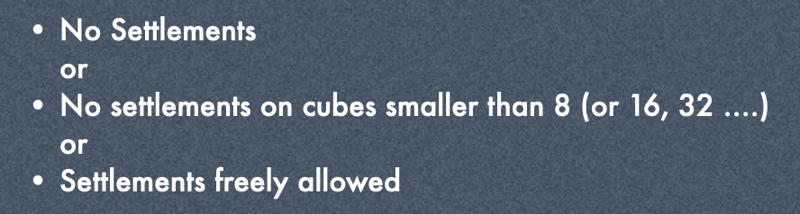

Settlements

There’s nothing like the excitement of winning or losing a game on a single decisive cast of the dice at the very end of a game, especially if the Box is facing a handful of cubes cranked up to ‘8’. For some folks, the volatility is too much to bear so they offer to pay, or collect a “settlement” commensurate with the actual value of the position on average. Typically, a player on either side might proclaim “I’m offering 3 points” or “I’ll take a point,” or simply yelp “Anybody wanna settle?“

Being able to calculate, or intuit, the fair settlement value of a position can be a challenging task, and a more savvy player can certainly exploit a less numerate player by offering a grossly unfair settlement — particularly if that player is fearful of losing “big” games. But these days, a position can be quickly entered into the XG Mobile app and reach a reasonably accurate figure. And of course no one is forced to accept a settlement they don’t find appealing, so where’s the harm?

The harm is that in some chouettes where settlements are allowed, certain players make a habit of negotiating them way too often, and it can slow the game down tremendously. Not only that, it can transform the most dramatic, consequential exchange of a backgammon game into a tedious and trivial haggling session. No one should need to “settle” a mere 4-cube. If you can’t stand to get gammoned on a 4-cube, it’s a clear sign you should find a less expensive chouette. So in some circles settlements are barred while in others a minimum cube value is specified for negotiations. In Boston we don’t have a rule because it just doesn’t come up very often.

Whatever your stated rule, it can be self-defeating to refuse a player genuinely distressed by an unusually large cube situation a fair settlement. Perhaps they are distressed because they cannot afford to pay the big loss they are staring down. Or perhaps after suffering that particularly painful loss, they settle up their losses and never return, leaving you to wonder why you had to be so mean.

Who Wins the Box?

Perhaps one of the most contentious rules that separates players from different locales is the question of what the player in the Box has to achieve in order to retain that position. When players from different cities get a chouette going on the side at major tournaments, there’s guaranteed to be a tedious argument about which policy is best.

The first option has the great virtue of simplicity. It’s unambiguous, and aside from some minor gamesmanship between Captain and Box among players willing to pay a little extra in cube equity to keep, or gain, the Box, it doesn’t motivate complicated cube strategies by a Box trying to engineer a net gain after passing some cubes.

On the other hand, some players seem to find it terribly unfair that the Box should get to continue there without showing a profit. They are not amused by the prospect of someone actually having a money-losing run in the box, which seems at least a little bit funny to the rest of us.

The sad part of it is that occasions where the Box beats the Captain but doesn’t show a net gain are really pretty unusual. You can play chouette for hours on end and never have it come up even once. People at tournaments often don’t realize they have a difference of opinion until the situation arises and then the usual tedious argument ensues. Best to just flip a coin if there’s disagreement, or go with the policy of whoever owns the board you’re playing on.

American players are unlikely to encounter the “last man standing” variation unless they travel abroad and wind up in a chouette hosted by the Brits, who find this diabolical rule entertaining. The idea is that the last player to be in the Captain’s chair when the Box is defeated earns the Box — no matter where they were in the line of succession. Here’s how that happens: some piratical soul on the Captain’s team sends a ridiculously early double, hoping that the Captain will subsequently “lose his market” at some point and earn a pass from the Box. The early doubler sits down and finishes out the game for the win and gains the Box, while the victorious Captain goes back to the end of the line!

Given that these chouettes often include 6-9 players, that deposed Captain will have a nice long wait before getting to sit down again . . . unless he stages a mutiny of his own. The Captain can ward off such an attack by doubling along with the early doubler — sort of a grim pact. But the early Doubler can also set off a chain reaction of cubes from anyone ahead of him in the order, and the net result may simply be an enormous equity dump to the Box, who sits upon a hoard of easy cubes.

Taking a Partner

A comfortable money stake can become less comfortable if the chouette grows to six players and beyond. In many playing circles, the practice is to split a 6-handed chouette into two 3-handed games, which has the virtue of giving everyone a lot more playing time. But big chouettes offer their own kind of fun, particularly on tournament weekends where you might have players dropping in and out of a chouette over the course of the day to fill time between matches. In such settings the Box is typically allowed to take a partner in order to moderate the potential damage of losing a big game.

A comfortable money stake can become less comfortable if the chouette grows to six players and beyond. In many playing circles, the practice is to split a 6-handed chouette into two 3-handed games, which has the virtue of giving everyone a lot more playing time. But big chouettes offer their own kind of fun, particularly on tournament weekends where you might have players dropping in and out of a chouette over the course of the day to fill time between matches. In such settings the Box is typically allowed to take a partner in order to moderate the potential damage of losing a big game.

The Box’s partner acts much as the teammates do with regard to the Captain, with the same consultation rules with the exception of cube action. Box partners are allowed to confer on cube decisions in a limited way: they may not discuss the reasoning behind their opinions, but only whether to take or drop cubes. At the end of the game, the Box and partner divide the net point result of the game evenly. If the result is an odd number of points, usually the actual Box pays or gets the extra point (or “the lion’s share”), although some players prefer to use half-points, or alternate who gets the odd point over several games.

With this many players, and with some taking partners, keeping track of the playing order can get tricky, so using slips of paper to maintain a player’s ladder is a great way to keep your chouette on track — and it also provides an easy way for all players to see how soon they might be playing at a glance. The player at the top of the ladder is the Box, and the losing player drops down to the bottom of the ladder. If the Box requests a partner, the player who just exited the Box remains at the top of the ladder, separated by a little space to tell the Box team apart from the Captain’s team. When the Box team loses, the Box partner drops back down to the bottom of the list — though in some variations, the partner is allowed to pop back into the order at the spot they would have occupied had they not been called upon to partner.

There can also be varying rules concerning whether players must consistently take or not take partners in the Box, or whether a player can refuse to act as partner to someone else. Often, circles of players make up these rules as situations arise — all that really matters is that rules be consistently applied.

Occasionally a player may ask whether they can pass up on playing in the Box altogether, just going around and around as a member of the Team and occasional Captain. This is generally disallowed as it would let a player rely substantially on other players’ talents without ever having to rely fully on their own.

Occasionally a player offers to be “perma-box,” remaining alone, win or lose, as opponents rotate amongst themselves. Players sometimes find this acceptable in one of two situations. First if the perma-Box is a highly-regarded personage whom the teammates feel privileged to compete with at all, or secondly if the perma-Box has an over-inflated sense of their own skill . . . and deep pockets.

Interlocking Chouettes

A novel approach to accommodating a large number of players without splitting into separate chouette is to split into two interlocking chouettes! The practice may have originated in the San Francisco Bay area in the 1970’s and has proven popular in thriving circles that regularly draw 6-12 players at a time.

The concept is simple, but the execution can be a bit tricky. Two tables are set up, preferably quite close together so that players on one table are able to look over at the other one without getting out of their chairs. All players participate in both games, any standard chouette rules apply, and there is a single order of succession for both tables, with the “on deck” player taking the Captain’s chair on whichever table finishes first. The score for each table is tallied separately, so using the “circle the loser” approach to tracking order should abandoned in favor of a “ladder” approach with names on slips of paper. Everything will also go more smoothly if you place the Box permanently on the same side of both tables so it’s always obvious to all players which side they are on for both games.

Players waiting for their turn to play can monitor the action on both tables, while seated Captain and Box players attend primarily to their own game and check out progress on the other as they can. But no one should expect to follow both games meticulously — let the Captains captain! When cube action emerges, the one table can pause and make their decisions, though seated players will probably want to go along with reasonable cube actions on the other table, as it will be easy to miss out on cubes as they focus on their own game. Unexpected glitches can occur when say the Box and Captain on Table 1 are the only remaining opponents of the Box on Table 2, but you just have to work through contingencies like that as best you can. Interlocking chouettes are not for tightly-wound, inflexible players.

Participants should be aware they they might have an unusually bad day if they fare poorly on both tables. Make sure you are comfortable with the stakes! But after all, it’s just the equivalent of playing two chouettes on different days more efficiently.

Further Resources

Many circles of players find it useful to draw up an explicit set of rules to govern local play. That way there will be no confusion over which standards have been agreed upon, and new players can be provided with a complete description of practices so they don’t find out about obscure regulations only when they arise during play.

Boston Chouette Rules

These are the traditions that have evolved and persisted among most competitors at NEBC events and Boston-area chouettes.

Other Rules:

Rules from the Laws of Backgammon (1931)

Atlanta Backgammon Association (ca. 2003)

Australian Capital Territory Chouette Rules (ca. 2015)

Brighton Backgammon Chouette Rules (UK)

Cambridge Backgammon Club Rules (UK)

Los Angeles Chouette Rules (ca. 2013)

Some Further Discussions:

Backgammon Galore! Chouette Discussions

Bill Robertie: How to Play Backgammon Chouettes Part 1 (2013)

Bill Robertie: How to Play Backgammon Chouettes Part 2 (2013)

Chouette Scoring Software

David Levy has written a windows program, The Chouette Scorer, that scores interlocking chouettes. It manages the rotation, allows individual cubes, lets players play for their preferred stakes, and more. Further details may be found in this User’s Guide. To learn more, contact David directly.

‘Big Money’ is based upon a photograph of a late night chouette at the Merit Open in Cyprus ca. 2018. To find out who’s who, or to buy a print, visit the Brighton Summer Open website.