by Albert Steg

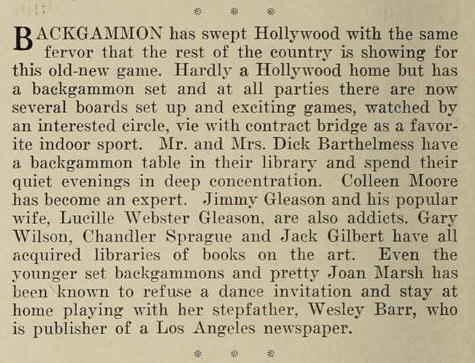

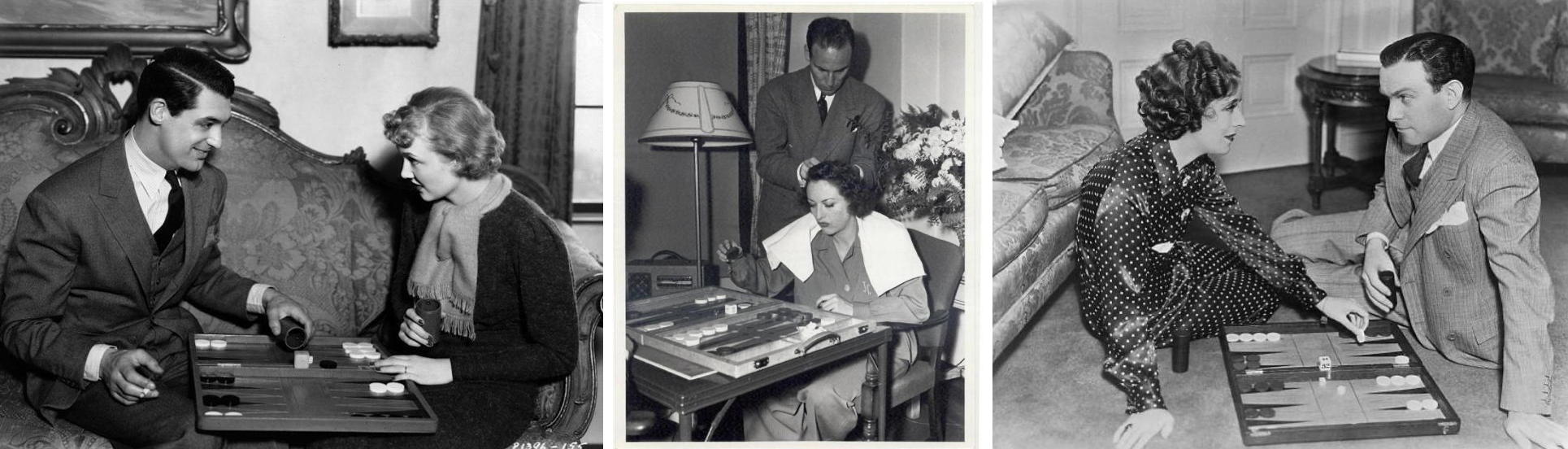

Backgammon enjoyed its first American boom in the late Jazz Age years of 1928 – 1931. It began a year or so earlier, in the milieu of French seaside resorts with the innovations of the doubling game and the chouette, which a coterie of American socialites adopted and transplanted to New York clubs and parlors, which in turn transmitted them across the United States in a proliferation of books, articles, lectures, and most of all, parties.

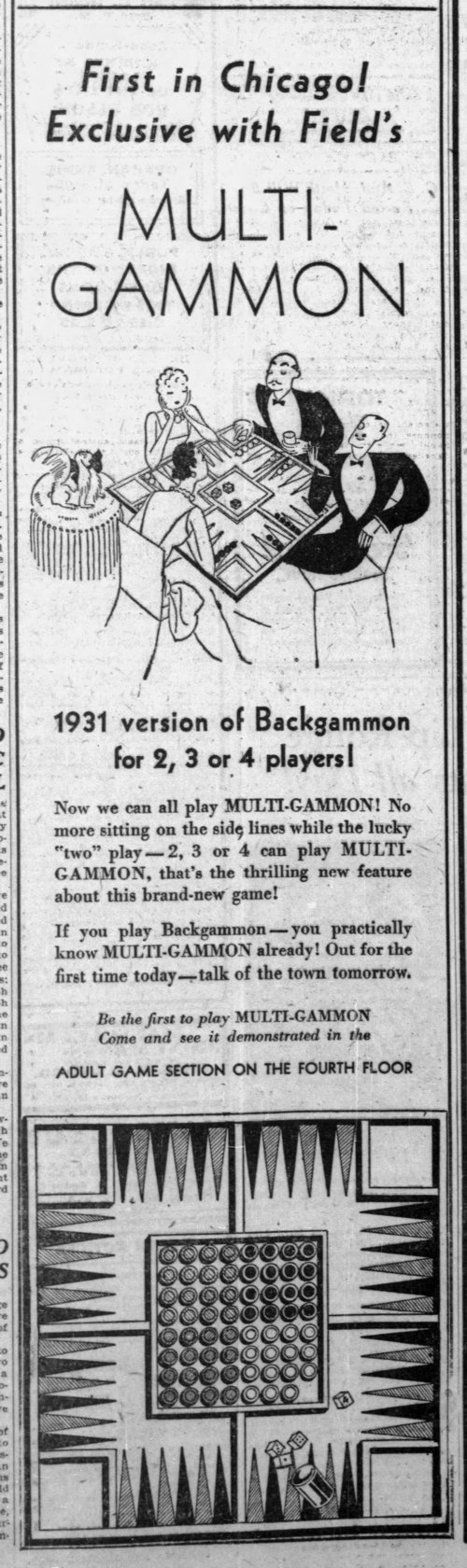

A newbie invited to the captain’s chair? Marshall Field & Co. advertisement, Chicago Tribune, June 17, 1930.

As backgammon enters its third major boom in the age of online and expert play driven by the wisdom of machines, it might be instructive to look back at what made the game so deliriously appealing to people without any of these resources. We have only to imagine playing long sessions of backgammon without a doubling cube to appreciate how transformational the introduction of “optional doubling” must have felt. But it was the social appeal of the chouette that made it ubiquitous among the the fashionable and well-heeled “smart set” of the day. Society hostesses seized upon it as the ideal solution to the problem of leftover party guests as groups of four settled down to their bridge tables after dinner and others came and went at all hours. Backgammon provided an ideal mixture of competitive intensity and conviviality — writers of the day frequently mention how amenable the game is to conversation and how little sustained concentration it requires, making it ideal for social mixing.

Chouettes remain popular today, but mostly only among committed money players who gather for that purpose. A key to the 1930’s boom is that backgammon was eagerly taken up within established social circles among people who would have been spending evenings together in any case. While today many players become friends through backgammon, back then, most discovered backgammon through their friends — or because it just became a fixture in their social circle whether they liked it or not. Look at the chouette scene in the ad to the right. How often are beginners today drawn into a chouette in their first weeks of play?

There is an irony in the thought that while backgammon in the 1930’s was popular among the very wealthy, the typical chouette stake among purely social players was probably a relatively harmless penny or nickel a point — or something less than a dollar in today’s money. (But they were wild with the automatic doubles!) Undoubtedly, there were large sums gambled among the most competitive players just as today . . . but where are the playful nickel or dime-a-point chouettes in the 21st century, played among friends and in-laws?

It’s hard to know how popular 1930’s backgammon was outside of private clubs and exclusive parties. It’s certainly true that the media was most interested in the well-to-do, whose mere seasonal comings and goings and newest hats were eagerly covered in newspaper Society pages. But in all the newspaper and magazine archives I searched, I found not a single mention of a public tournament or club or gathering apart from department-store promotions. The boom of the 1970’s was clearly a much broader phenomenon, reflected in the proliferation of local clubs playing in public spaces and the popularity of “Open” tournaments.

Backgammon in the 2020’s often seems haunted by a sharkish nostalgia for the 1970’s, when the oceans were full of easy prey (and where we all imagine ourselves the predators). But maybe if we were more nostalgic for the social graces of the 1930’s milieu, more people would want to play with us.

All photographed items from collection of Albert Steg unless otherwise noted.

Early Signs . . . (1928)

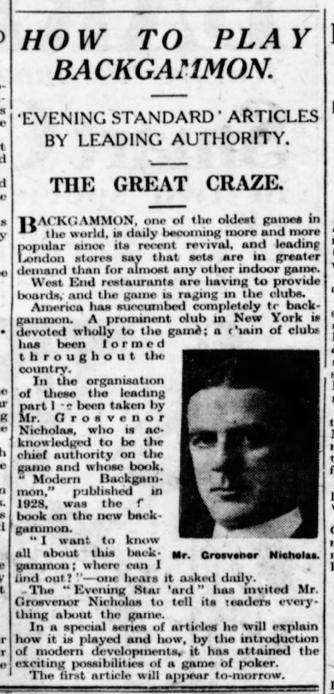

London Evening Standard, Jan. 9, 1928

From The Nashville Banner, Mar. 25, 1928.

References to backgammon in newspapers and magazines won’t proliferate until 1930, but even before Grosvenor Nicholas’ book was published, there were a few hints of the mania to come. London’s Evening Standard was very early to pick up the signal, and would publish a major series of backgammon articles by Nicholas in 1931.

A “Literary Gossip” columnist (at right) got wind of the Nicholas book before publication and mentions a “lumberman” already preparing to cash in on the backgammon revival by mass-producing boards.

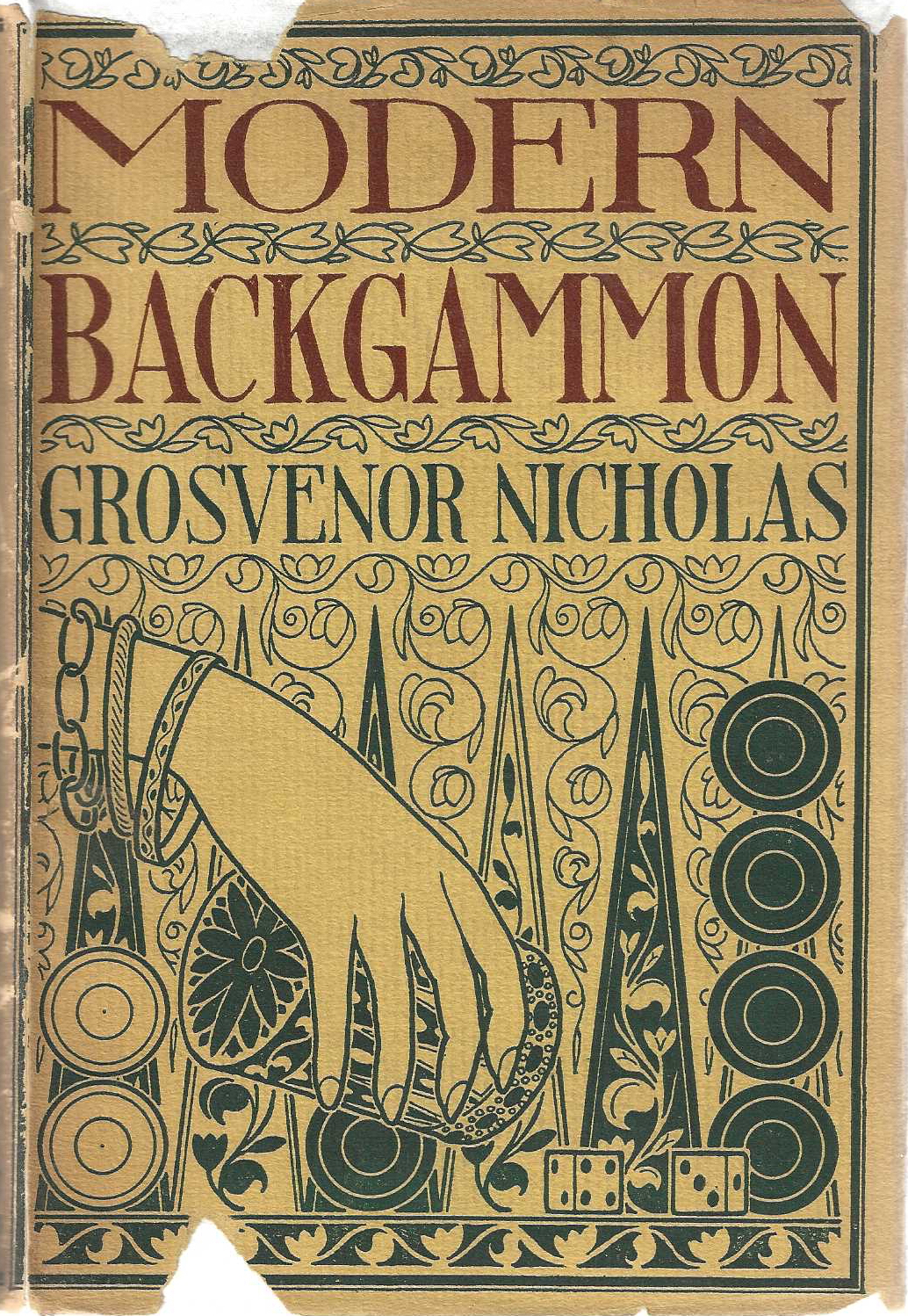

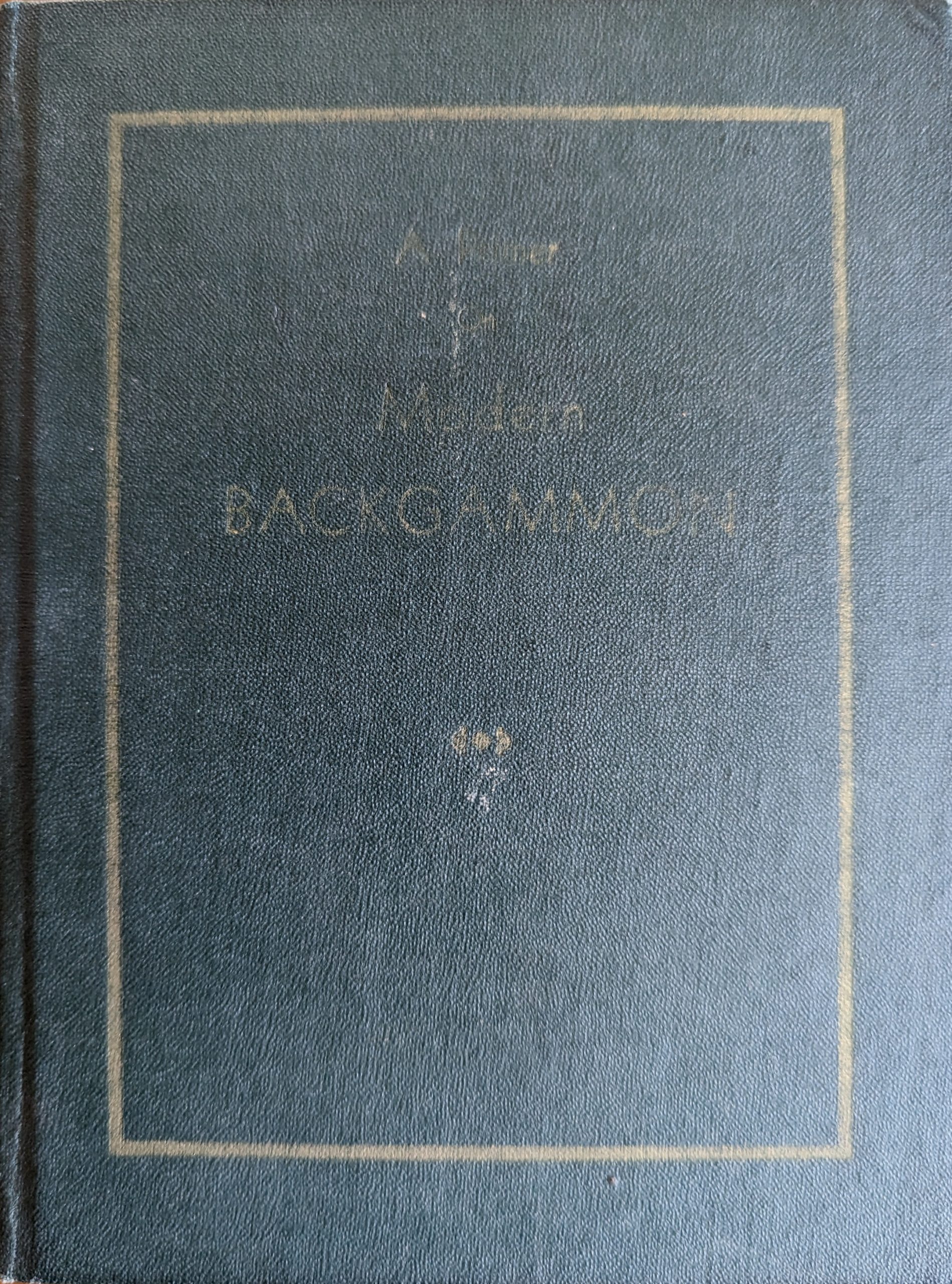

Modern Backgammon (Apr. 6, 1928)

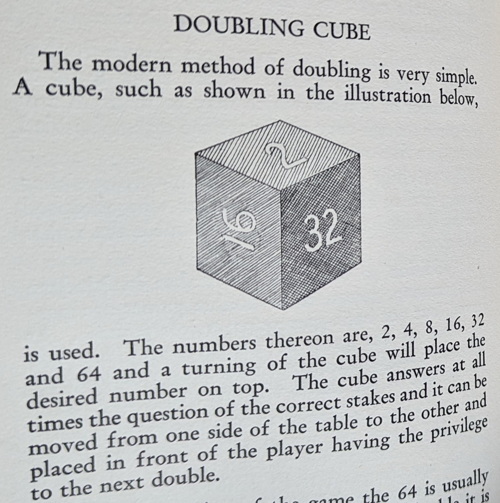

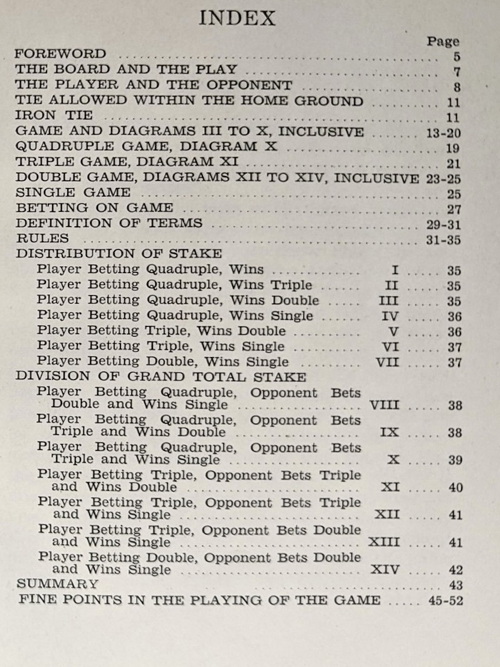

Modern Backgammon, p.23.

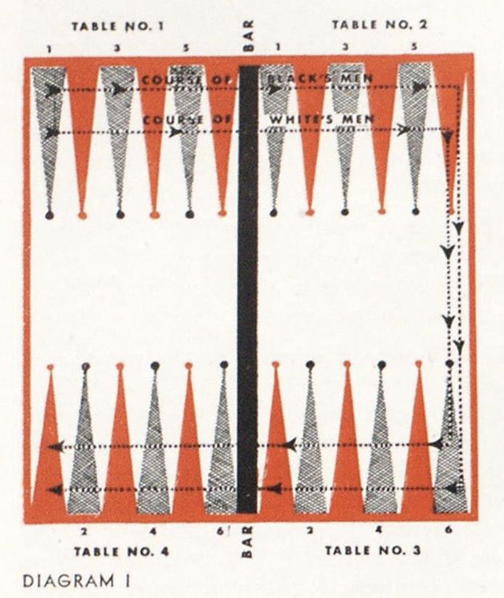

The figure of Grosvenor Nicholas looms large over the history of 20th century backgammon. His Modern Backgammon stands apart from all the other backgammon texts of its day . . . by over two years. The first book in the 20th century devoted entirely to backgammon, its influence would be hard to overstate, for it introduces for the first time in print the twin innovations of doubling and chouette play. While Nicholas didn’t invent either practice, his book led the way in spreading the word about these new ways of playing backgammon. The book is also rich in descriptions of various informal or optional aspects of the game, such as practices of gamesmanship (he approves of “selling” doubles through feigned diffidence), automatic doubles, and points of proper behavior across the board.

The figure of Grosvenor Nicholas looms large over the history of 20th century backgammon. His Modern Backgammon stands apart from all the other backgammon texts of its day . . . by over two years. The first book in the 20th century devoted entirely to backgammon, its influence would be hard to overstate, for it introduces for the first time in print the twin innovations of doubling and chouette play. While Nicholas didn’t invent either practice, his book led the way in spreading the word about these new ways of playing backgammon. The book is also rich in descriptions of various informal or optional aspects of the game, such as practices of gamesmanship (he approves of “selling” doubles through feigned diffidence), automatic doubles, and points of proper behavior across the board.

Nicholas presents a clearly-reasoned argument in favor of slotting plays on the opening roll (62, 53, 51, 43, 41, 32, and 21) , asserting that “position” must take precedence over “progress” (the 1930’s term for “race”) in the early game. He also articulates a clear preference for the 5 point over the bar point for all the right reasons. The entire section on opening rolls shows a nice sense of the salient issues, and acknowledgment that it is often hard to say which is the “best” play.

Today’s reader might also be impressed that Nicholas’ exposition of the three “forward” types of games (running, shut out, and blocking) are consistent with our current thinking about the basic game plans. Nicholas characterizes the back game as a worthy innovation that can provide a skillful player an opportunity to overcome inferior dice rolls — when the dice favor you in neither “progress” nor “position.” But he is clearly alive to the gammon risk of such a strategy, particularly when it comes to accepting a double. Nicholas explicitly addresses the “too good to double” scenario, and implicitly suggests awareness of a “doubling window” — though this conceptual terminology would not emerge for several decades yet.

Ironically, Nicholas’ prose is anything but modern. Ponderous sentences larded with references to antiquity make for heavy going in the sections of text that aren’t explaining the mechanics of the game. There’s none of the brisk, careless, tone more characteristic of the “jazz age” sensibility that would appear in later accounts of the game in publications like Vanity Fair or The New Yorker, or the several books that would follow in 1930.

"Bridge or Backgammon?" (Vogue, Sept. 14, 1929)

By late 1929, backgammon had become wildly popular in “fashionable” New York circles, but the game had not yet broken out to a point where the newspaper and magazine media had taken much notice. This Vogue article by Frank Crowninshield, editor of the magazine, stands alone in that calendar year as a substantial acknowledgment of the game’s renaissance. Presciently, he opens with a reflection on the appetite for “higher risks, higher stakes, higher hazards” in the air at the time, just one month before the great stock market crash that followed in October. Crowninshield characterizes innovations in contract bridge as well as backgammon as manifestations of the prevailing rage for “higher gambling,” and goes into some detail on the rules and consequences of “doubling by matches” and multi-handed chouette play.

By late 1929, backgammon had become wildly popular in “fashionable” New York circles, but the game had not yet broken out to a point where the newspaper and magazine media had taken much notice. This Vogue article by Frank Crowninshield, editor of the magazine, stands alone in that calendar year as a substantial acknowledgment of the game’s renaissance. Presciently, he opens with a reflection on the appetite for “higher risks, higher stakes, higher hazards” in the air at the time, just one month before the great stock market crash that followed in October. Crowninshield characterizes innovations in contract bridge as well as backgammon as manifestations of the prevailing rage for “higher gambling,” and goes into some detail on the rules and consequences of “doubling by matches” and multi-handed chouette play.

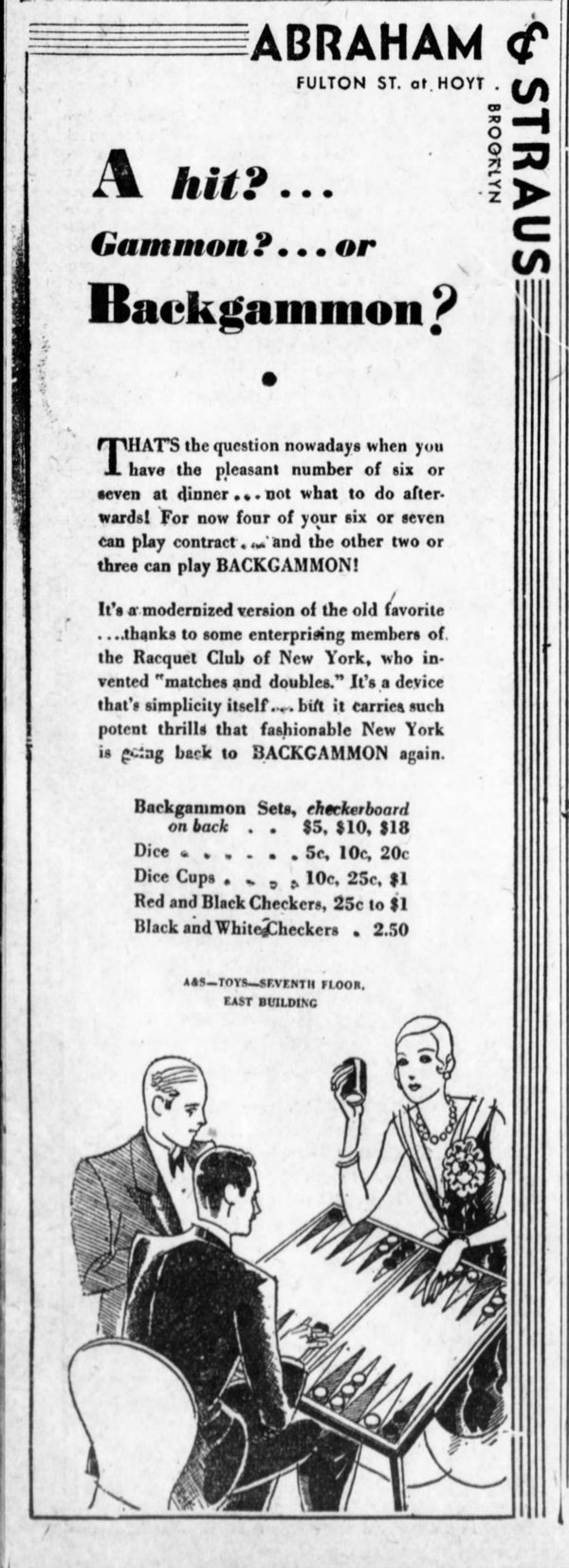

Advertising Firsts (Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Oct. 10, 1929 / Chicago Tribune, May 26, 1930)

First depiction of chouette? Brooklyn Daily Eagle, New York, Oct. 2, 1929

Major department stores took a keen interest in backgammon, perhaps not only because of the market for selling expensive equipment, but also because of the game’s popularity among the deep-pocketed social elite. In addition to backgammon paraphernalia, stores frequently hosted backgammon lectures, and some even engaged published authorities of the game as house experts.

The storied Brooklyn department store Abraham & Strauss was very early to the field with the ad at left. The advertising copy emphasizes the social problem backgammon solved by providing a gaming activity for excess dinner guests at bridge parties, so although the man at tableside looks a lot like a waiter, the illustration might reasonably be interpreted as the first known depiction of a chouette. Otherwise, the Marshall Field ad at right claims two firsts.

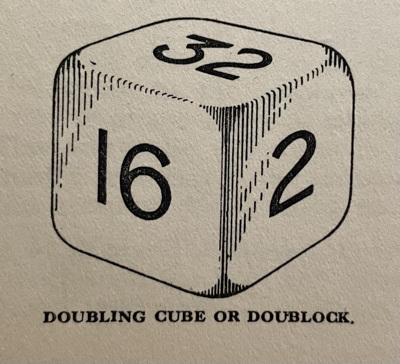

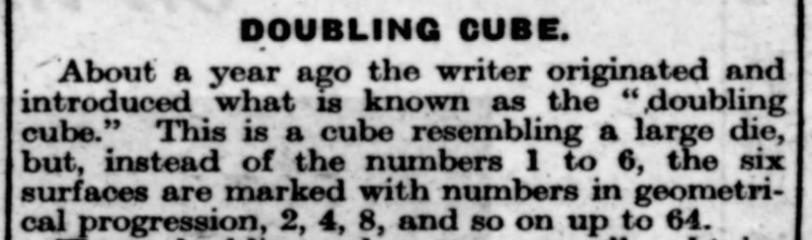

Marshall Field & Co. in Chicago has the distinction of having published the first known depiction of a doubling cube, several months later. In a London article written in mid May 1931, Grosvenor Nicholas would refer to having “originated and introduced” the doubling cube “about a year ago,” so the cube offered in this ad must have been among the very first offered for sale. The unknown illustrator for Marshall Field includes two cubes in the ad, as well as a lively chouette scene of his own. One gets a sense he or she was no stranger to the game.

The headline of the A&S ad plays on the traditional terminology for single, double, and triple wins in backgammon. The term “hit,” now obsolete, was the old term for a single game. Hoyle, for instance, would refer to “playing for the hit” as opposed to “playing for the gammon.”

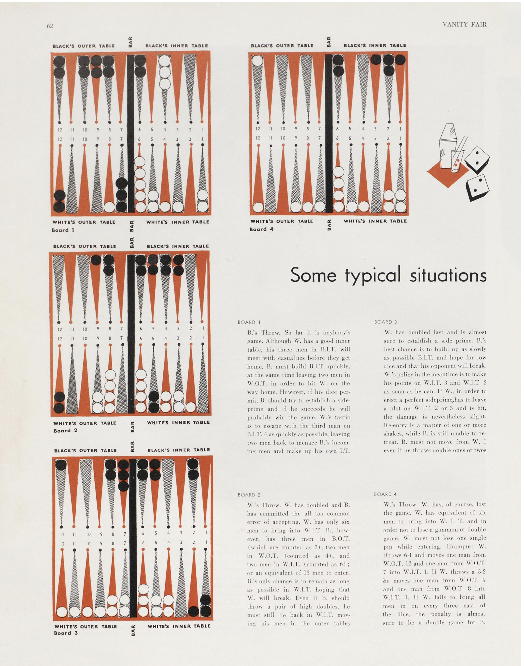

"Enter Backgammon" . . . (Vanity Fair, June - July - August, 1930)

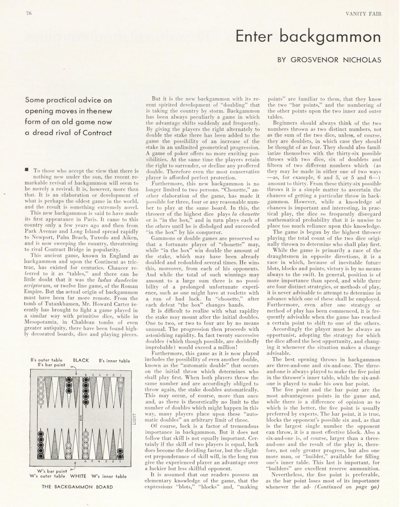

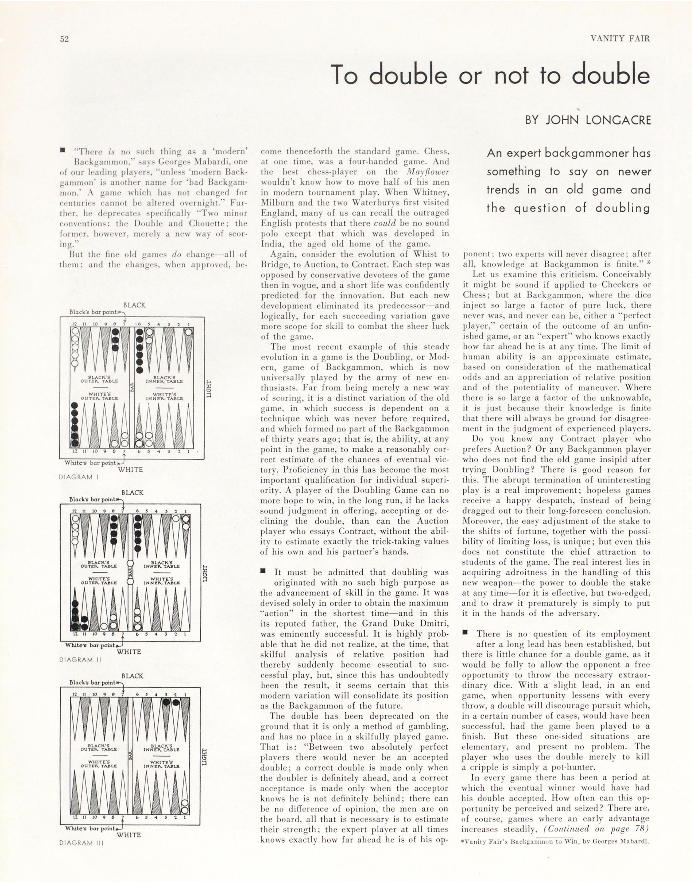

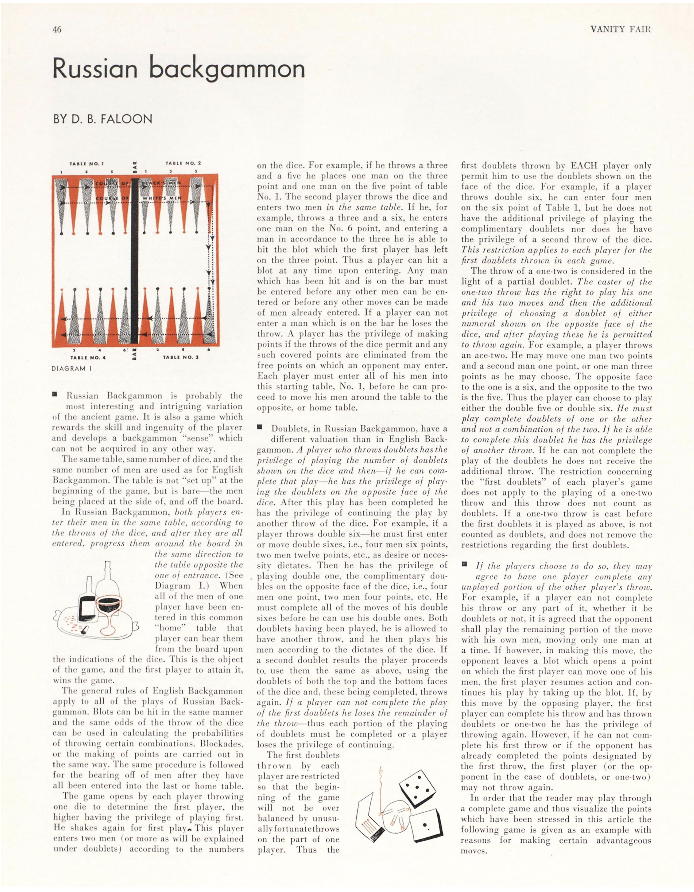

Grosvenor Nicholas appears at the head of the 1930 cascade of backgammon books and articles, offering a trio of articles in Vanity Fair over the summer. The articles assume basic knowledge of how to play, and go straight into material for experienced players. The first installment, “Enter Backgammon” (June) traces the origins of the Modern game (doubling and chouettes) to Paris, and in passing mentions that in the multi-player game “the thrower of the highest dice plays la chouette, or is ‘In the box’.” The image of “playing the owl” fending off attackers is vivid and colorful and it seems a shame the less poetic “in the box” became the standard expression instead. Nicholas goes on to cover the opening plays much as he did in his book. The second article, “The Strategies of Backgammon,” continues the discussion of the more difficult opening plays and then outlines the basic “game types” also covered in his book, and the final installment is devoted to “The Back-game Strategy.”

A Primer on Modern Backgammon (July 1, 1930)

Image: Levy Collection

Bond Primer, p. 40 (Levy Collection)

Ralph A. Bond was first out of the gate with a book in 1930, self-publishing this 45-page ‘Primer’ on the game on July 1st in Chicago. Its scarcity on the collector’s book market reflects the likelihood that it was printed in a single run of limited quantity. Aside from two copies of the book submitted to the Library of Congress copyright office in 1930, few are extant, but according to one book owner, David Levy, the Primer is largely the same text re-published in New York as Bond’s Beginner’s Book of Modern Backgammon a few months later, but newly set to type with different paginations.

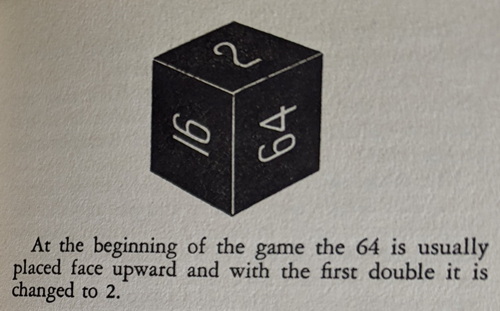

Of greatest interest is that Bond is the first backgammon writer to describe the use of a doubling cube to track game value (the Primer includes the same illustration as appears in the Beginner’s book). What’s more, the fact that Bond’s Primer was published in Chicago is significant: the 720 North Michigan Avenue address on the title page was just a few blocks from Marshall Field & Company, the first known merchant to advertise doubling cubes for sale a few months earlier (see above). The way that Bond characterizes the cube as the standard method (“a cube . . . is used”) along with the Fields ad might suggest that it was Chicago, not New York, where this modern device first took hold. (Elizabeth Clark Boyden’s book published the same month, does not mention the cube).

Bond also published a smaller booklet, Backgammon as Played Today, in August, perhaps intended for inclusion in backgammon sets of the time.

Bond also published a smaller booklet, Backgammon as Played Today, in August, perhaps intended for inclusion in backgammon sets of the time.

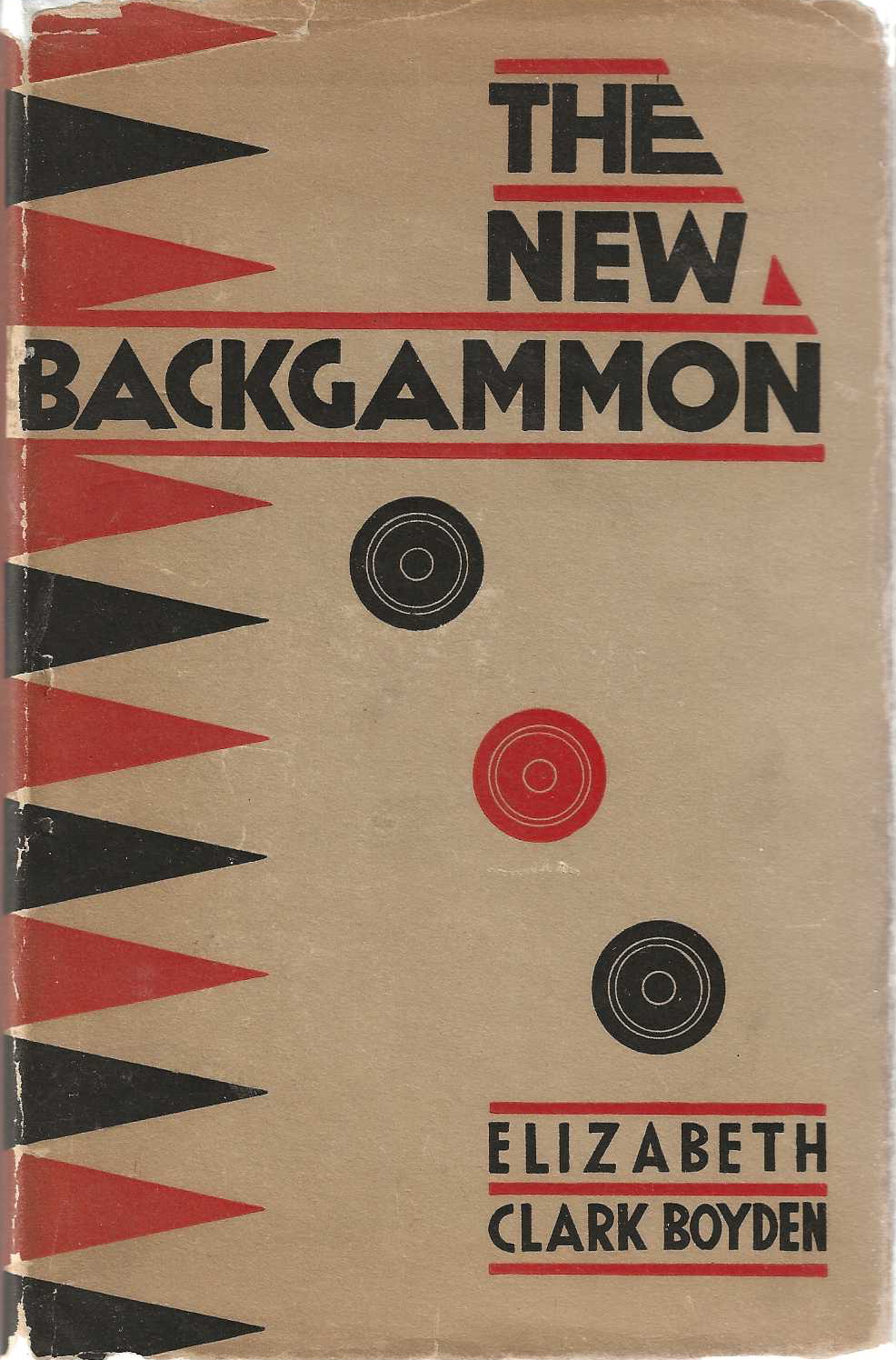

The New Backgammon (July 17, 1930)

A Boyden diagram illustrates the use of match sticks for automatic and optional doubling.

In a Foreward dated June 5th, 1930, Elizabeth Clark Boyden affirms that “About 18 months ago backgammon awoke from its Rip Van Winkle Sleep, and suddenly became the mode at the smart summer resorts in the East,” once again confirming that the craze for the game was well underway in 1929 before the media (and book publishers) caught up in 1930.

In a Foreward dated June 5th, 1930, Elizabeth Clark Boyden affirms that “About 18 months ago backgammon awoke from its Rip Van Winkle Sleep, and suddenly became the mode at the smart summer resorts in the East,” once again confirming that the craze for the game was well underway in 1929 before the media (and book publishers) caught up in 1930.

Boyden’s book is perhaps most useful to historians for the detail she brings to “new” backgammon practices in separate chapters on “Doubles,” “Chouette” and “Scoring.” In the latter section she provides a detailed example of how accounts were settled using various methods of scoring “by games” or “by checkers” and including both automatic and optional doubles tracked by using match sticks. That she makes no reference to a doubling cube in the book is consistent with its only having been introduced that spring.

Boyden includes accurate examples of efficient play in racing home: “Always play the man which can be moved into the next table with the fewest wasted points, rather than a man which can be moved so he stays in the same table,” and gives some attention to bearing off safely against an ace-point anchor. Her enumeration of game types (which she characterizes as choosing a “playing policy”) omits the “Shut Out” game covered by Nicholas, but she will include it in her newspaper series later in the year.

Boyden was also a published authority on contract bridge. Her New York Times obituary reveals she lived in Natick, MA and died just two years later in February 1933 at the age of 55.

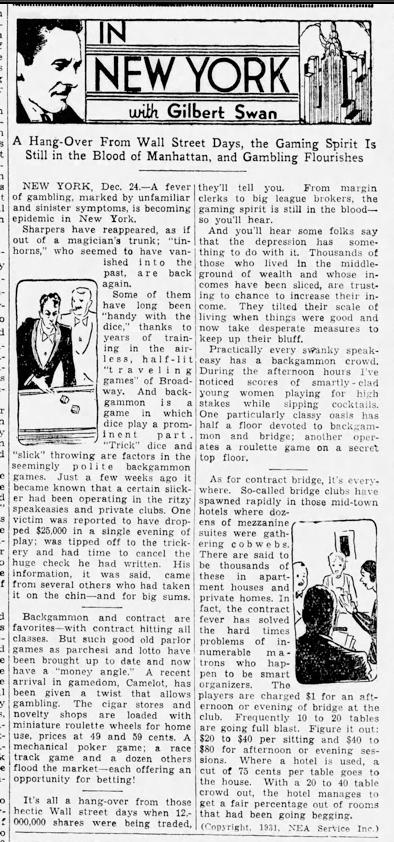

"In New York" with Gilbert Swan (Palo Alto Times, Aug 14, 1930)

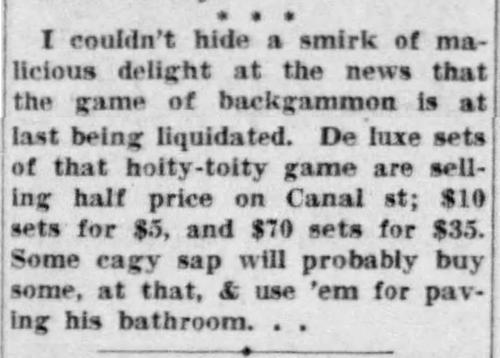

Gilbert Swan is not a name that has endured in the annals of journalism, but his In New York column appears to have enjoyed wide syndication in 1930-31. His persona is that of a lightly satirical, detached observer keeping his audience up to date on the newest foolishness going on in the big city.

Gilbert Swan is not a name that has endured in the annals of journalism, but his In New York column appears to have enjoyed wide syndication in 1930-31. His persona is that of a lightly satirical, detached observer keeping his audience up to date on the newest foolishness going on in the big city.

Swan looks slightly askance at the sudden rage for backgammon driving book sales and $25 hourly fees for instructors (around $400 in 2020’s dollars), “For, after all, when anything new — however old it may be — hits New York, they grab at it as the well known drowning man clutched for the life preserver , or whatever it was. Once New York has taken it up, the quick witted promoters will see to it that the rest of the country discovers it ere long.”

Swan would devote further columns to backgammon in 1931, featured further down the page in this timeline.

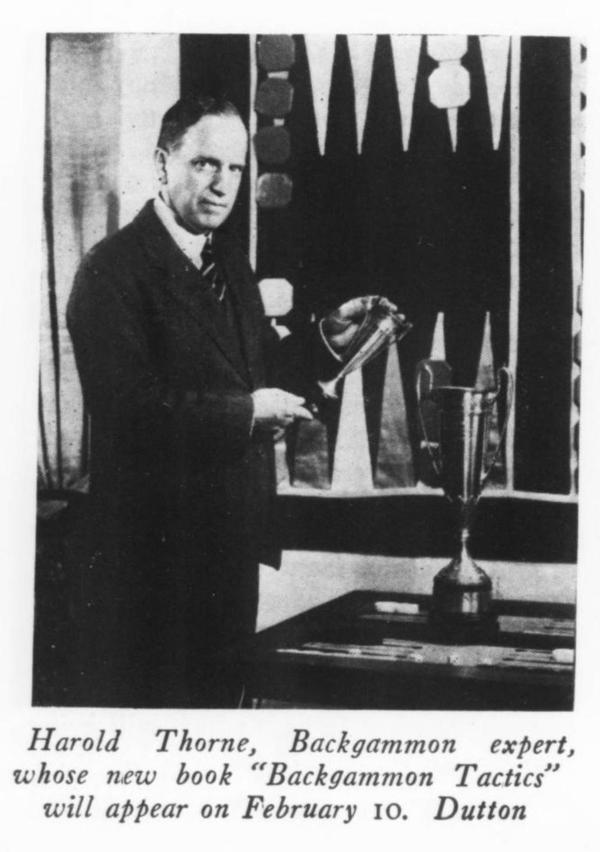

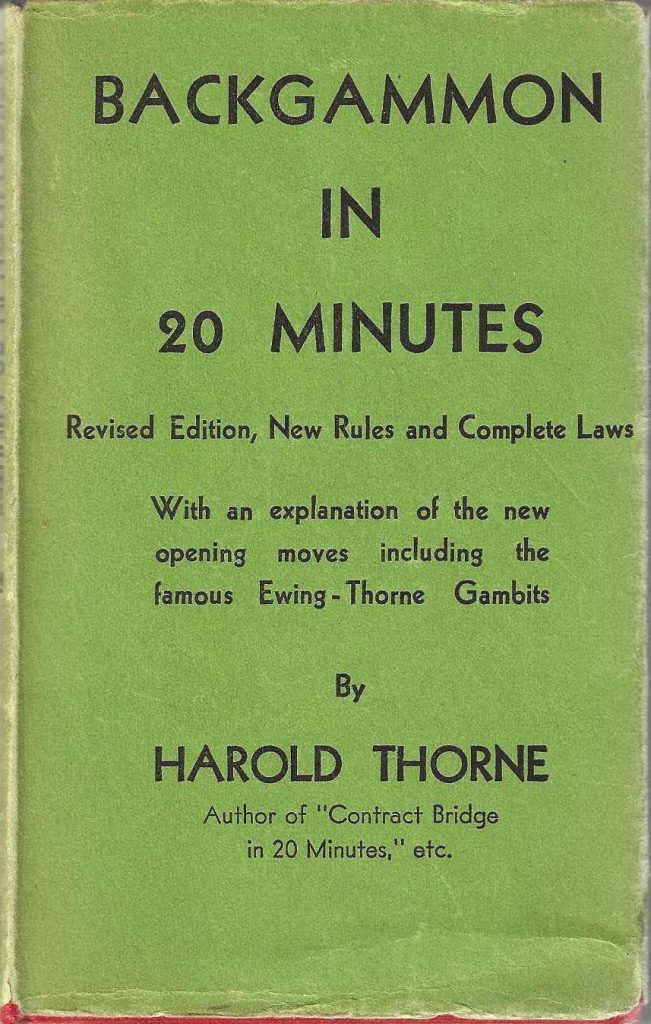

Backgammon in 20 Minutes (Aug. 22, 1930)

The Publisher’s Weekly, Jan. 31, 1931.

Rare copy of 7th printing (Nov. 1930), and the 3rd revision of the book in the space of four months. 8th and 9th printings appeared in December.

Harold Thorne’s handy little text must have sold like hotcakes — by Sept. 30th, just five weeks after publication it was on its 5th printing, and had already earned a “Revised” edition, and by November was in its 7th printing, including yet more revisions explaining the opening play “Ewing-Thorne Gambits,” which are mixture of splitting plays (21, 32, 43) and middle-eastern style “two up” plays (62, 63), and a radical 64 play making the deuce point — all of them quite unusual for the time. These innovative plays are featured in his newspaper column How to Play Backgammon published in Oct-Dec. of this year.

Thorne apparently had a good nose for the business side of publishing, marketing score pads for 25 cents a pop in a style where you needed a fresh sheet for every game. They include fanciful terms for members of the Captain’s crew in chouette: 1st Mate, Bo’sun, and . . . Cabin Boy. Oddly, the sheet indicates a backgammon costs a further double, rather than a triple score per the longstanding convention of the game (and his own chapter on scoring). There appears to have been a range of conventions around scoring backgammons at the time, from no extra penalty (encouraging back-gamers to hang in to the bitter end) to a brutal 4x penalty. Thorne also acknowledges “the Philadelphia method” of scoring in which players according to the number of checkers remaining on the board — in which case gammons and backgammons are not factored in (but doubles made in the course of the game are).

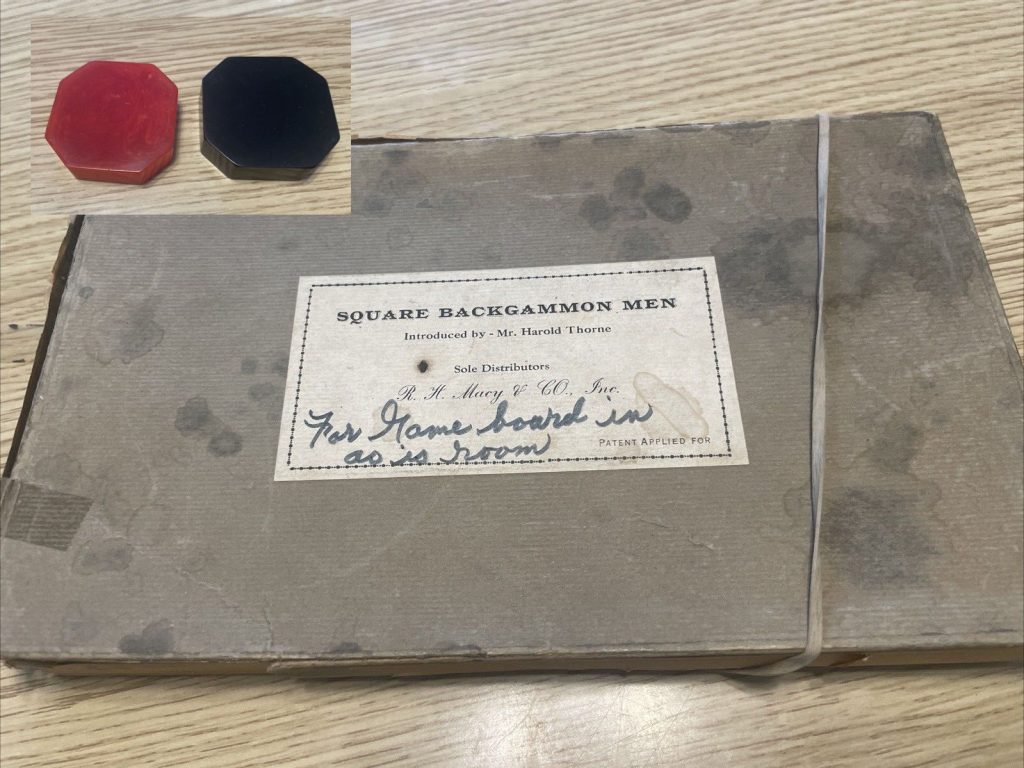

A more notable endeavor was his (apparently failed) attempt to patent “square” (actually octagonal) backgammon checkers, which he marketed through R. H. Macy, evidenced in this picture from an eBay auction. His novel checkers are also visible on the lecturing board in the photo at right. Although these checkers seem to have sold fairly well in the early 1930’s, they didn’t prove popular enough to endure beyond then — probably because they just aren’t as easy to pick up as round ones.

A rare boxed set of Thorne’s “square” checkers, “patent applied for” ca. 1930-31. (photo: ebay)

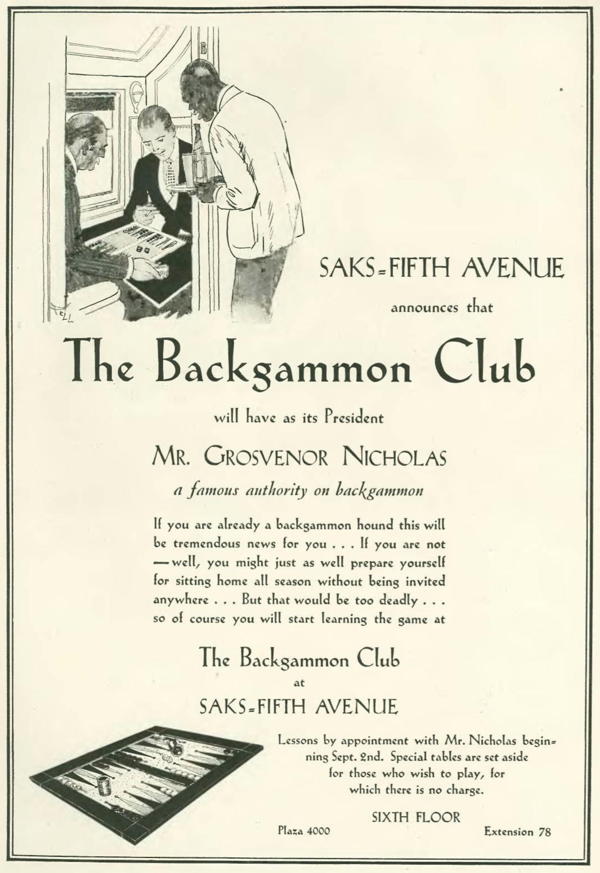

Saks-Fifth Avenue Backgammon Club (Aug. 1930)

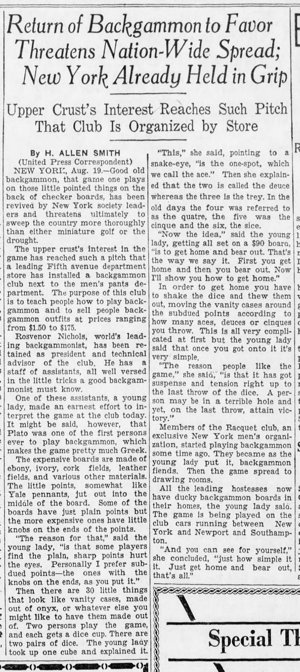

It seems that department store “clubs” were the closest thing to a public backgammon club in the jazz age, and not really what we would think of as a backgammon club in the 21st century. The idea appears to have been to devote a room in the store to backgammon, making tables available for players and shoppers to mingle and learn the game, enticing them to buy equipment. Adding the imprimatur of a known authority like Grosvenor Nicholas adds status to the endeavor, but we needn’t imagine him whiling away his afternoons there. As the article at right explains, he had “a staff of assistants all well versed in the little tricks a good backgammonist should know.” Similar department store “clubs” or lectures were offered around the country, including Carson Pirie, Scott in Chicago and Bullock’s in Los Angeles in the months to come.

The illustration of privileged backgammoners in the Saks ad may reflect the oft-mentioned popularity of backgammon on the New Haven line in and out of New York City.

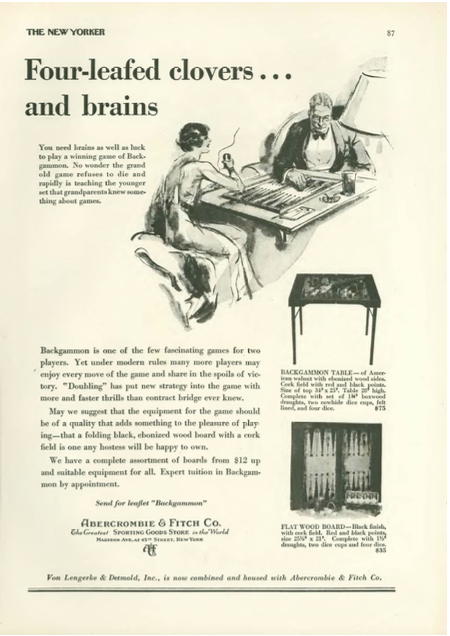

"Tric Trac, Clic Clac" (The New Yorker, Sept. 6, 1930)

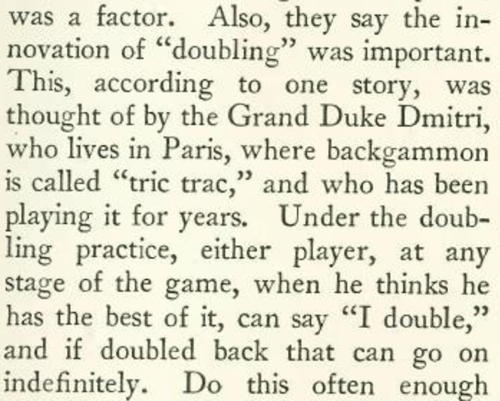

Included in the Talk of the Town section, this breezy take on the resurgence of enthusiasm for backgammon includes a few interesting historical comments regarding the cyclical interest in such games, the purported invention of doubling by the Grand Duke Dmitri of France, and a story, almost certainly apocryphal, of Grosvenor Nicholas winning thirty-five games in a row at the racquet Club in New York.

Included in the Talk of the Town section, this breezy take on the resurgence of enthusiasm for backgammon includes a few interesting historical comments regarding the cyclical interest in such games, the purported invention of doubling by the Grand Duke Dmitri of France, and a story, almost certainly apocryphal, of Grosvenor Nicholas winning thirty-five games in a row at the racquet Club in New York.

The article concludes by name-dropping a range of aristocratic devotees of the game, as well as two horses running at the time, Chouette and Backgammon.

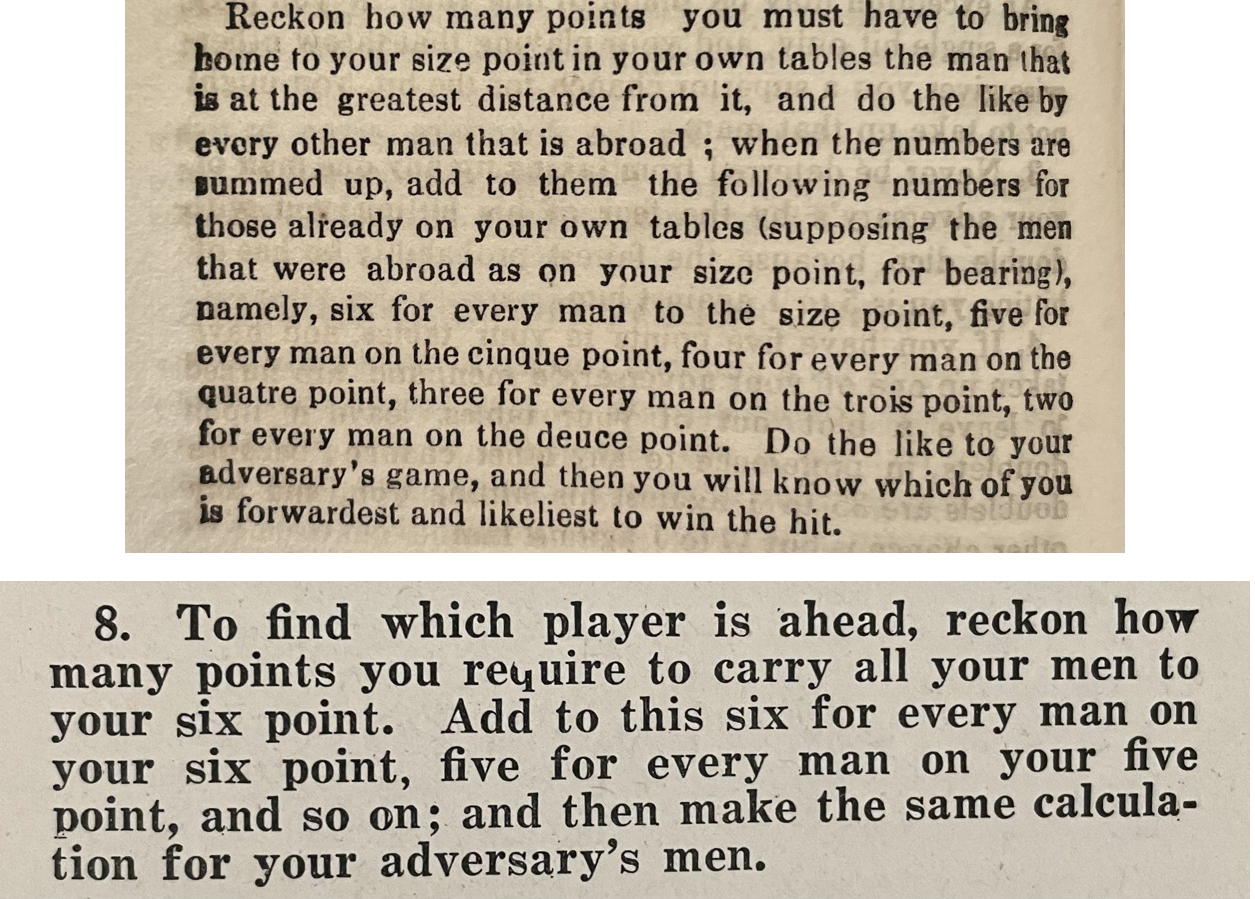

How to Play the New Backgammon (Sept. 12, 1930)

Leila Hattersley, seated at right, offers instruction. ca. early 1930’s.

Leila Hattersley’s How to Play the New Backgammon was easily the most readable and engaging book up to this point. Her writing shows a keen sensitivity to the way that new players experience and learn the game, and perhaps as a result she offers a lot of interesting detail for the backgammon historian. Hattersley writerly skills are no fluke: she was the daughter of author Kate Chopin, best known for the proto-feminist novel The Awakening (1899).

Leila Hattersley’s How to Play the New Backgammon was easily the most readable and engaging book up to this point. Her writing shows a keen sensitivity to the way that new players experience and learn the game, and perhaps as a result she offers a lot of interesting detail for the backgammon historian. Hattersley writerly skills are no fluke: she was the daughter of author Kate Chopin, best known for the proto-feminist novel The Awakening (1899).

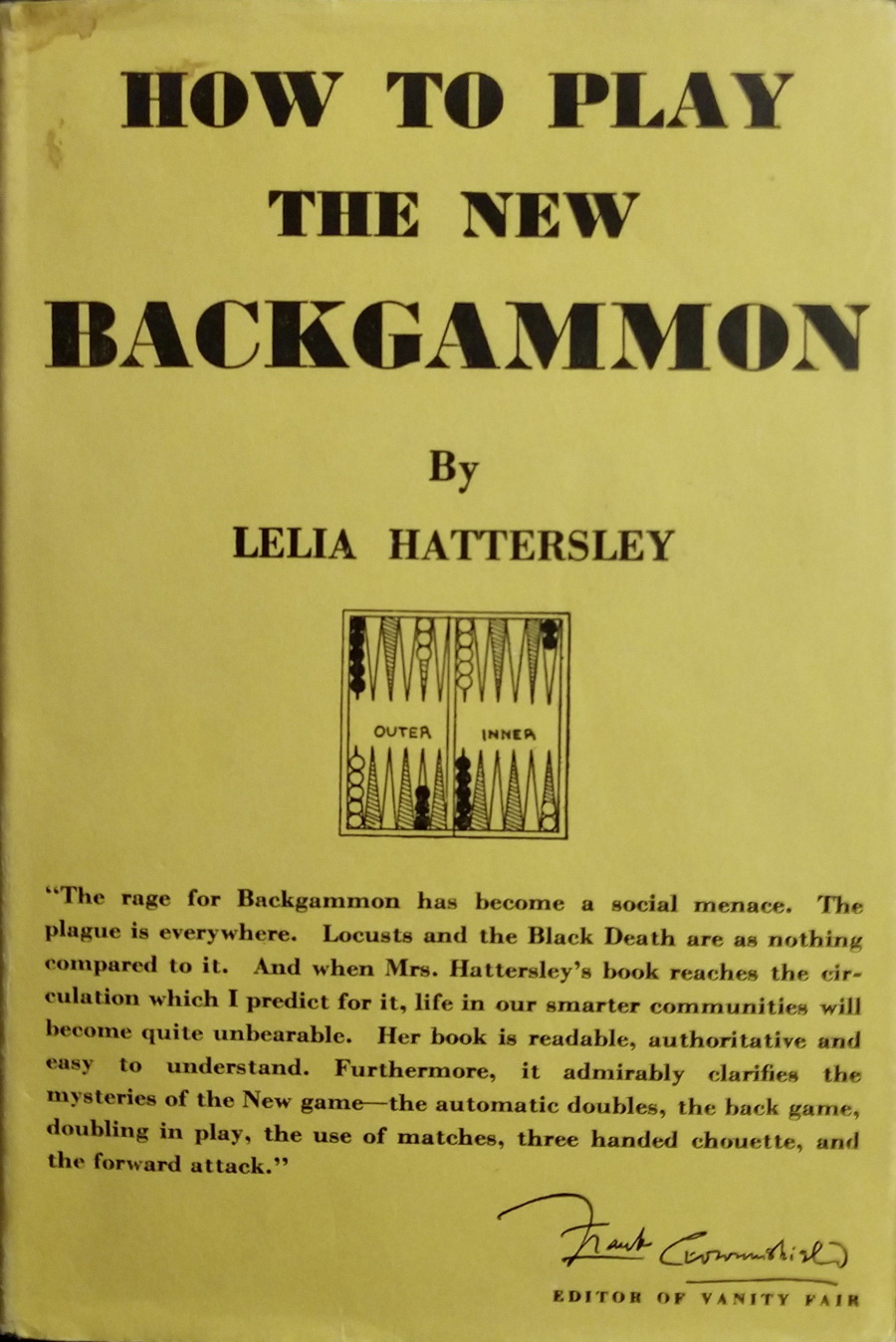

Hattersley includes a section on using a doubling cube, which she must have welcomed, given that she badly muddles her section on “Scoring with matches”. She also helpfully explains how a Captain in chouette must take over the equity of a crew member who dissents from a decision to accept a double offered by the Box (“taking an extra” in today’s terminology).

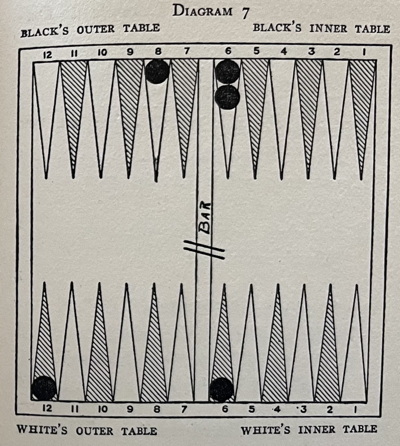

In a deft and colorful rhetorical strategy, she assigns military titles to the four groups of checkers in the starting position for ease of reference: Runners, Reserves, Musketeers, and Guardsmen (see diagram at lower left). Her opening play advice reflects some of the prevailing taste for slotting rather than splitting (though neither term had been invented yet).  Only 54 earns a grudging license to split, as a second-place option that is “dangerous but sporting.” Appetite for slotting the 5-point even with rolls such as 43 and 23 might be explained by the willingness of expert players to adopt an all-out Back Game when dice favored the opponent in the opening exchanges.

Only 54 earns a grudging license to split, as a second-place option that is “dangerous but sporting.” Appetite for slotting the 5-point even with rolls such as 43 and 23 might be explained by the willingness of expert players to adopt an all-out Back Game when dice favored the opponent in the opening exchanges.

Hattersley offers for the first time titled sections on the three “forward games” (Running, Blocking, Shut-out) acknowledged by Grosvenor Nicholas as well as a separate chapter devoted to the Back Game and Counter-Back game strategies. These essential game types have endured to the current day, though the strategic option of playing a high-anchor holding game when the forward strategies fail had not yet been explicitly formulated. The inherent value of what we call an “advanced anchor” seems not to have been so thoroughly appreciated — reflected in Hattersley’s aversion to splitting on the opener, shared by many of her peers as well.

A somewhat edited section of the book providing doubling tips appeared in The October issue of Vanity Fair under the title “The New Backgammon.”

How to Play Modern Backgammon (Sept. 20, 1930)

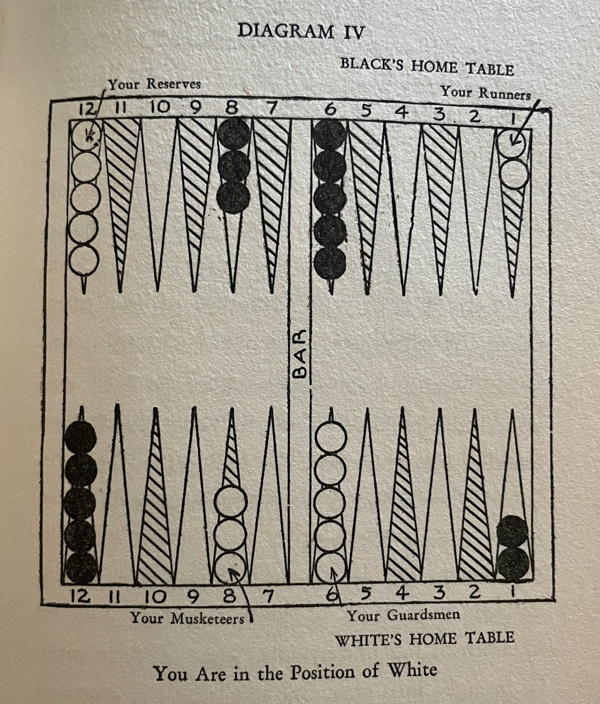

Two versions of the pip-count. From Hoyle’s Games, (1845), and a paraphrase by J.S. Ogilvie (1930)

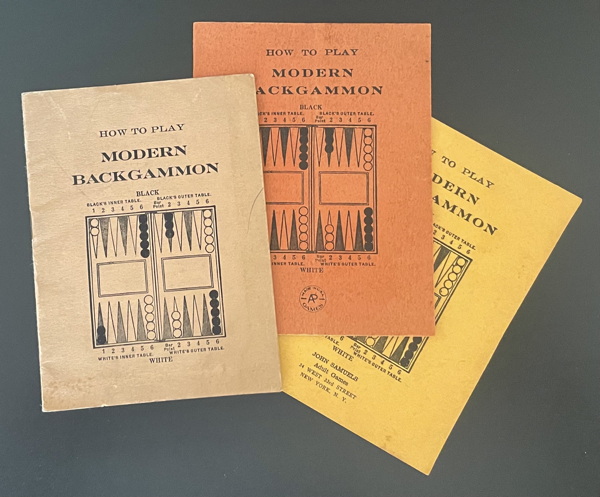

Original 1st printing and two subsequent printings by games distributors.

This 16-page booklet has no named author but was copyrighted by J.S. Ogilvie Publishing Company, New York. It is a peculiar amalgam of material cribbed from 19th-century Hoyle texts as well as more contemporary sources. For instance, while it includes the now obligatory explanations of optional doubling and chouette play, it employs the obsolete language of playing for a “hit” (a single game as opposed to a gammon), and includes a close paraphrase of Hoyle’s version of . . . the pip count! It’s a startling inclusion, as the pip-count seems to have gone dormant for the 1930’s, with authors referring only vaguely to evaluating “progress” by counting crossovers to bring checkers into the home board.

A hasty copyright acknowledgment added to the Abercrombie & Fitch printing (1930).

Another oddity of this pamphlet is that it includes “The Official Rules as adopted by the leading New York Clubs” two weeks before they would be published under fresh copyright by John Longacre and Grosvenor Nicholas in Backgammon of Today. This appropriation, whether nefarious or perhaps just a case of mistaken timing in the publication of the two texts, appears to have led to some manner of dispute as a version of the Ogilvie booklet printed under an Abercrombie & Fitch cover and including an equipment catalog section (see farther down this page), bears a hastily added acknowledgment on the ‘Rules’ page (at right).

The rights to the Ogilvie book were subsequently bought by Three Sirens Press, an odd holding for a small press with only about a dozen entries registered in the Library of Congress Copyright records at the time, mostly popular literary titles. Three Sirens appears to have managed printing of the booklet for inclusion in popular backgammon sets of the day marketed by AP Games and John Samuels Adult Games among others (see booklet imprints above). Copies of the booklet can occasionally be spotted in ebay auctions for vintage equipment.

The rights to the Ogilvie book were subsequently bought by Three Sirens Press, an odd holding for a small press with only about a dozen entries registered in the Library of Congress Copyright records at the time, mostly popular literary titles. Three Sirens appears to have managed printing of the booklet for inclusion in popular backgammon sets of the day marketed by AP Games and John Samuels Adult Games among others (see booklet imprints above). Copies of the booklet can occasionally be spotted in ebay auctions for vintage equipment.

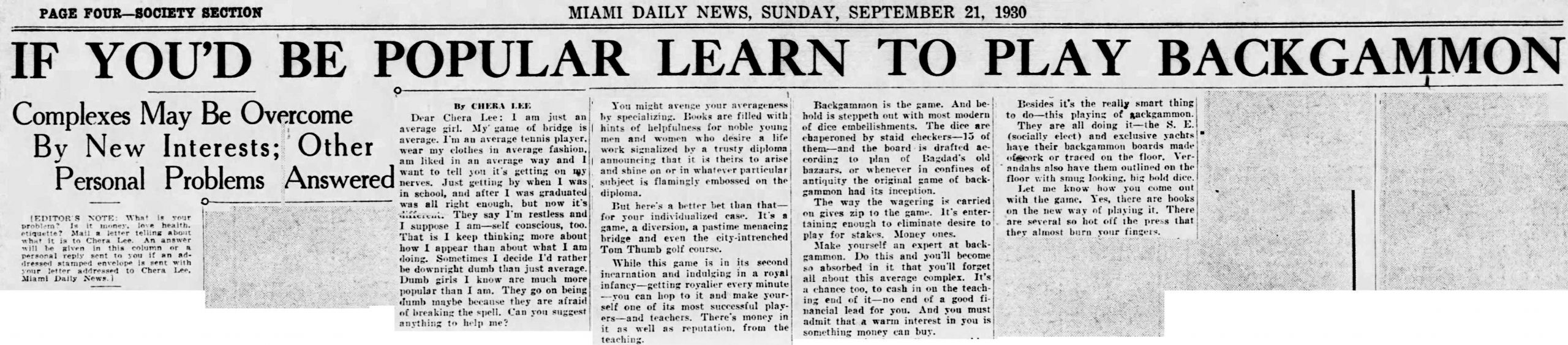

"If You'd Be Popular Learn to Play Backgammon" (Miami Daily News, Sept. 21, 1930)

Imagine a world where backgammon has so much social cachet that it might be offered as a solution to a young lady’s restless feeling of inadequacy. This brief advice column includes several telling details. The description of the dice being “chaperoned by staid checkers” is a nod to the potentially unseemly association of backgammon with rude gambling activities. (There was a running joke at the time about backgammon being essentially a game of craps with fancy rules.) Chera Lee’s prescription for our moping socialite is to become a local authority on the game, reflecting the broad dissemination of backgammon expertise through lectures and lessons predominantly attended by women. “Society” hostesses were eager to feature backgammon as part of their dinner parties or weekend gatherings, and proficiency at the game might afford an otherwise unremarkable girl a chance to shine — and to earn some pin money, or more, at the same time.

"Backgammon Returns With a Bang as Social Sport" (Indianapolis Times, Sept. 22, 1930)

First dated photograph of a doubling cube.

Syndicated articles such as this one from the NEA reporting on the vogue for backgammon in New York and Long Island could be picked up by papers across the country, alerting hostesses to the social cachet of the game: “Dragging out a backgammon board when a new young man calls is now considered not only a fine way to get a slant on his I.Q. but also to rate him socially.” The article also attests to the popularity of the game on commuter rail cars, something frequently alluded to in ads and articles of the time.

The photograph, supplied by A.G. Spalding, shows off an elegant table of the day and features the first dated photograph of a doubling cube. Spalding, well known for its sporting equipment, offered backgammon items for sale in The New Yorker for the 1930 holiday season. That they helpfully provided the photo for this feature might suggest that the board pictured is one of their creations. The article also goes into some detail describing a variety of expensive sets currently available, as well as related paraphernalia, from backgammon-themed linens and china to “smoking things” (humidors? ash trays?).

'How to Play Today's Backgammon' (Syndicated Column, Sept. - Oct., 1930)

Boyden describes the new-fangled doubling cube in the 11th installment of her series.

Elizabeth Clark Boyden didn’t just mail in excerpts of her July book for her 14-part syndicated newspaper column, but re-worked parts of it substantially, while also providing new updates on game developments such as the doubling cube (see passage at right), which hadn’t come into use by the time she submitted her final draft of The New backgammon for publication. A more committed historian may wish to compare all of her opening roll proscriptions to see whether they evolved over the intervening months, but the rest of us will find most intriguing the greater detail with which she describes doubling (article 11), chouette (article 12), scoring by matches or cube (article 13), and scoring by checkers (article 14).

The complete PDF file of the series at left is composed of the most legible scans of the articles, published in New York, Indiana and Florida from late September to mid-October.

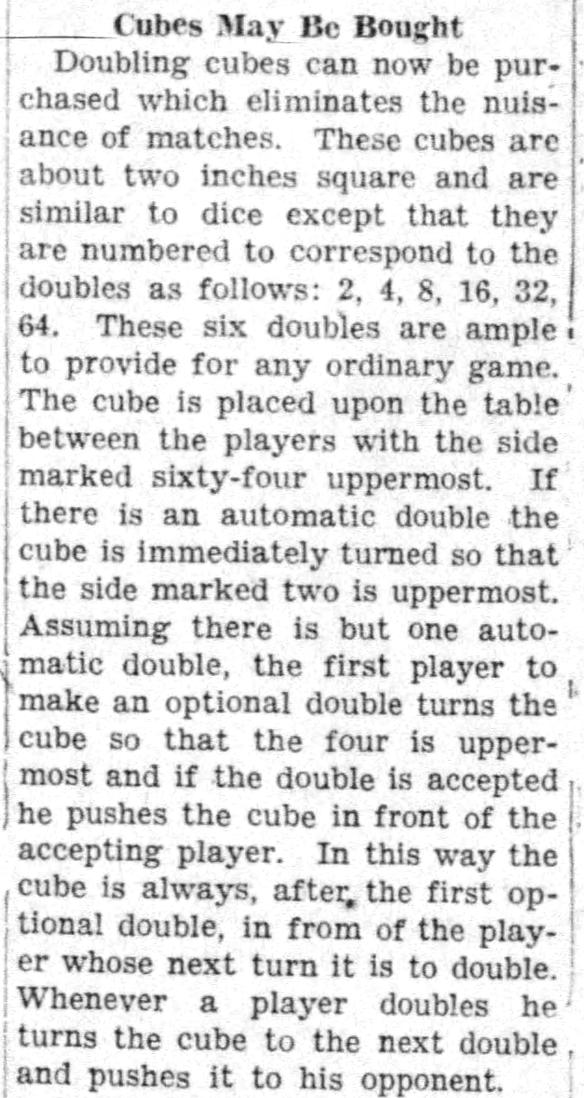

Beginner's Book of Modern Backgammon (Sept. 30, 1930)

This book is a substantially re-edited and extended version of Bond’s A Primer on Modern Backgammon, self-published just three months earlier in Chicago — this time from a New York publisher. In between there was also a pamphlet, “Backgammon as Played Today” sent to the Library of Congress for copyright on August 29th. The new Beginner’s Book includes more detail about the history, practice and strategy of the game, for example providing some rationales for the best opening plays rather than simply stating them.

This book is a substantially re-edited and extended version of Bond’s A Primer on Modern Backgammon, self-published just three months earlier in Chicago — this time from a New York publisher. In between there was also a pamphlet, “Backgammon as Played Today” sent to the Library of Congress for copyright on August 29th. The new Beginner’s Book includes more detail about the history, practice and strategy of the game, for example providing some rationales for the best opening plays rather than simply stating them.

Detail from Bond, Third Revised printing, Dec. 1930, courtesy Levy Collection.

Bond seems to have been particularly enthusiastic about the introduction of the doubling cube, listing it as a distinct, third modern innovation that has “done so much to popularize the modern phase of the game as it makes clear at a glance the stakes and the players standing in the game.” (p.10). He dismisses the use of matches as “antiquated” — noting that players have come to liken them to a “cord of wood” stacked on the bar in games with several doubles.

Bond would publish a third version of his book in December with substantial revisions including an updated illustration of the doubling cube featured in his July and September books. As detailed in the Early Doublers & Cube Evolution section, his new version adheres to the arrangement of numerals that appears to have been more or less standard in 1930.

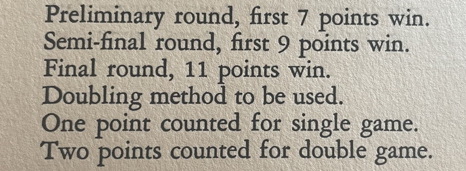

A further notable inclusion in the book comes on its final page, where Bond briefly specifies match lengths for tournament play, something not addressed in any other book of the year. It seems that progressive — and odd-numbered — match lengths have been a tournament practice for a very long time. It seems that for a time backgammons (triple games) fell out of use in competitive play.

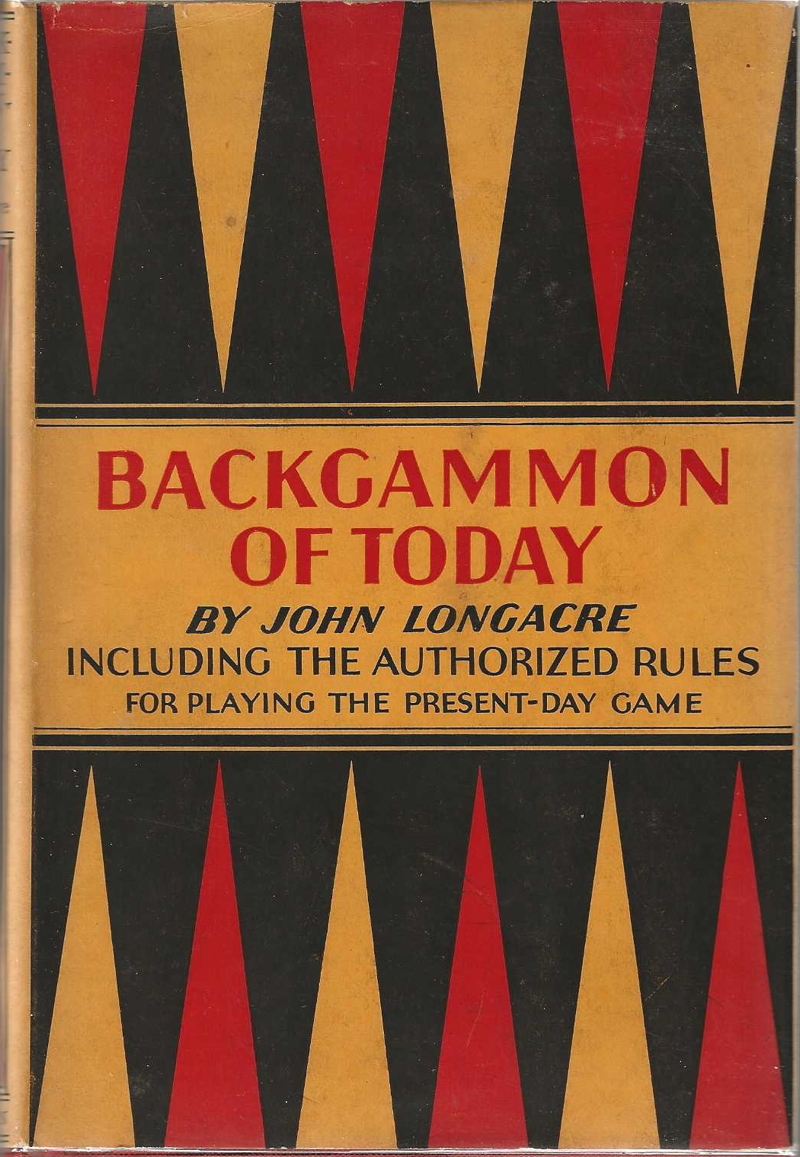

Backgammon of Today (Oct. 1, 1930)

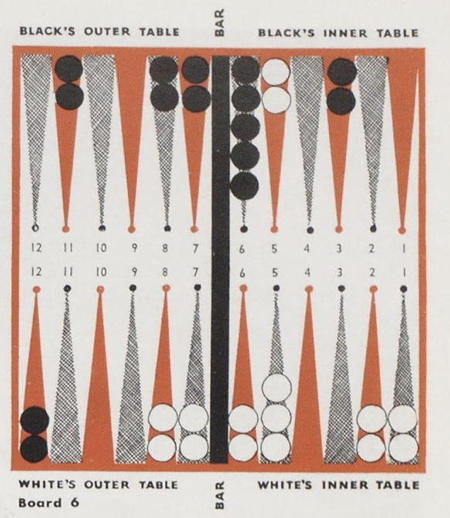

Backgammon of Today (p.93)

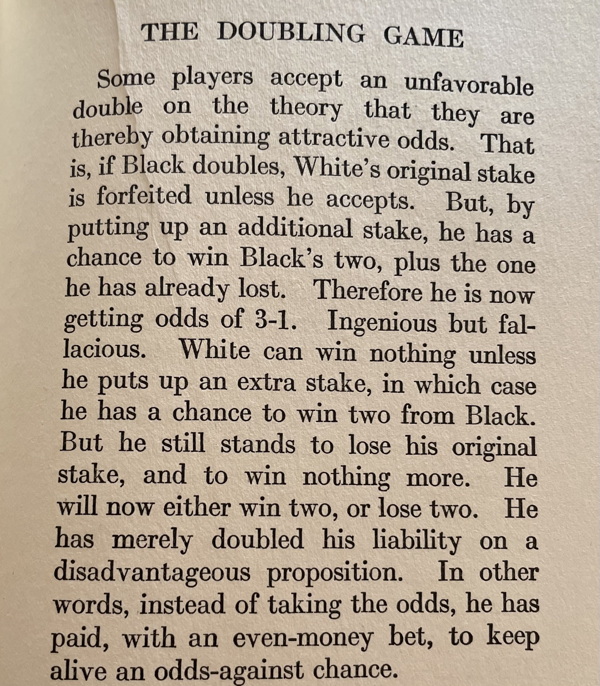

John Longacre’s Backgammon of Today is most notable for including an early attempt to codify the Rules of Backgammon by general agreement of “the clubs where the game has been longest played, and where the modern variations have been developed.” Longacre’s hope that a more deliberately vetted code might be developed and promulgated by a formal committee of club representatives would come to fruition a year later, in 1931.

John Longacre’s Backgammon of Today is most notable for including an early attempt to codify the Rules of Backgammon by general agreement of “the clubs where the game has been longest played, and where the modern variations have been developed.” Longacre’s hope that a more deliberately vetted code might be developed and promulgated by a formal committee of club representatives would come to fruition a year later, in 1931.

The book is rich in color regarding the contemporary wisdom of experts. In his treatment of the opening plays (which are intriguingly varied among the various books published that year) Longacre slots the 5 point less aggressively than Hattersley, but goes all out with 64, 63, and 62 — slotting the bar with all of them! In another departure from formula, he does not include the “Shut Out” as one of the basic game types, but offers “The Game of Position” instead — a sort of vaguely defined combination of offense and defense that may be a precursor to what we call a Holding Game.

In a passage that does Longacre least credit, he dismisses the notion current among “some players” that the taker of a double enjoys 3-1 odds on the proposition (see passage at right). This shows that a version of the “25% Rule” was in circulation at the time, but had not yet become settled backgammon wisdom.

In early 1931 Longacre published a syndicated newspaper series on backgammon, but unlike series by Boyden and Nicholas, it appears to have been simply excerpted directly from this book, and is therefore of little interest.

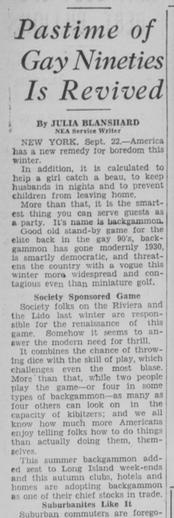

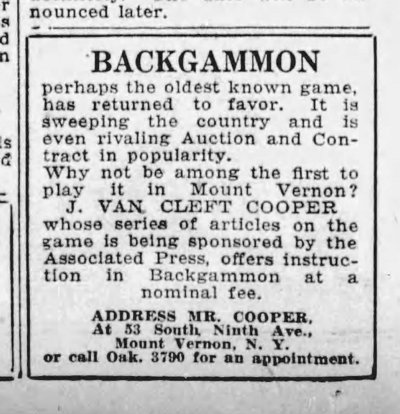

Learn Backgammon in 5 Minutes a Day (Oct. 1, 1930 . . . )

Mount Vernon Argus, Oct. 9, 1930

J. Van Cleft Cooper, a crossword compiler of some note, will be a new name for most backgammon scholars as he did not author a book on backgammon, but he did publish this 6-part introduction to the game. It was carried in various newspapers starting in early October in American city papers as far flung as the Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Of particular interest is the 4th installment, which provides a quite detailed account of the use of matches for scoring. In Van Cleft’s account, each match represents one point . . . but he quickly confuses himself miscounting matches and doubles, in the process showing why people must have been relieved when the doubling cube came along.

The six articles compiled in the PDF file at left were drawn from various papers in order to use the best quality scans for each piece, so the numbering scheme of the sections indicated in the columns themselves is inconsistent as some papers split or combined material in different ways.

Winning backgammon at Sight (Oct. 15, 1930)

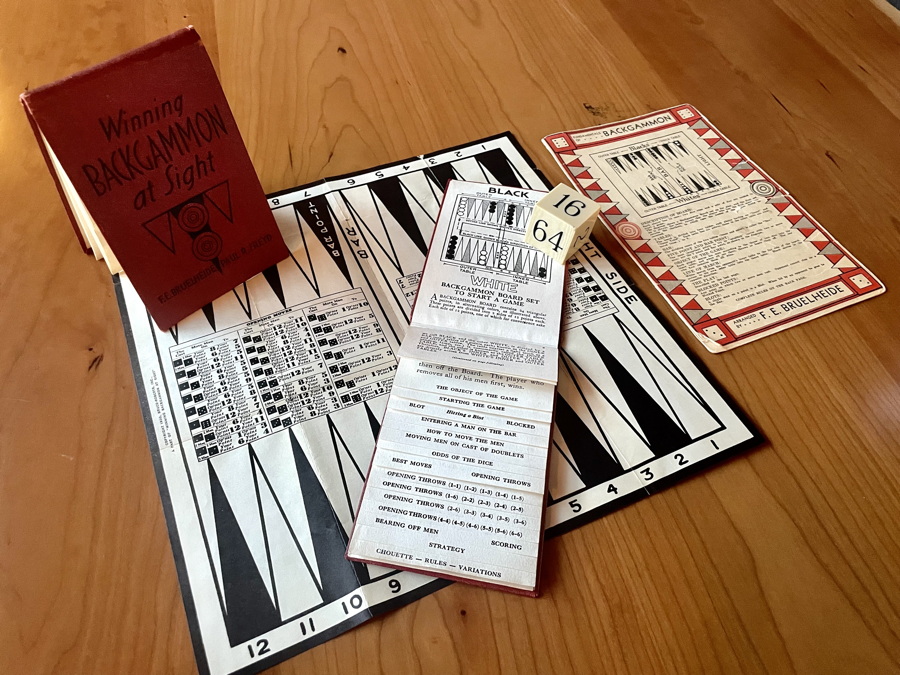

Two copies of of the booklet, along with separate Bruelheide “Fundamentals” pamphlet, and period doubling cube, all ca. 1930.

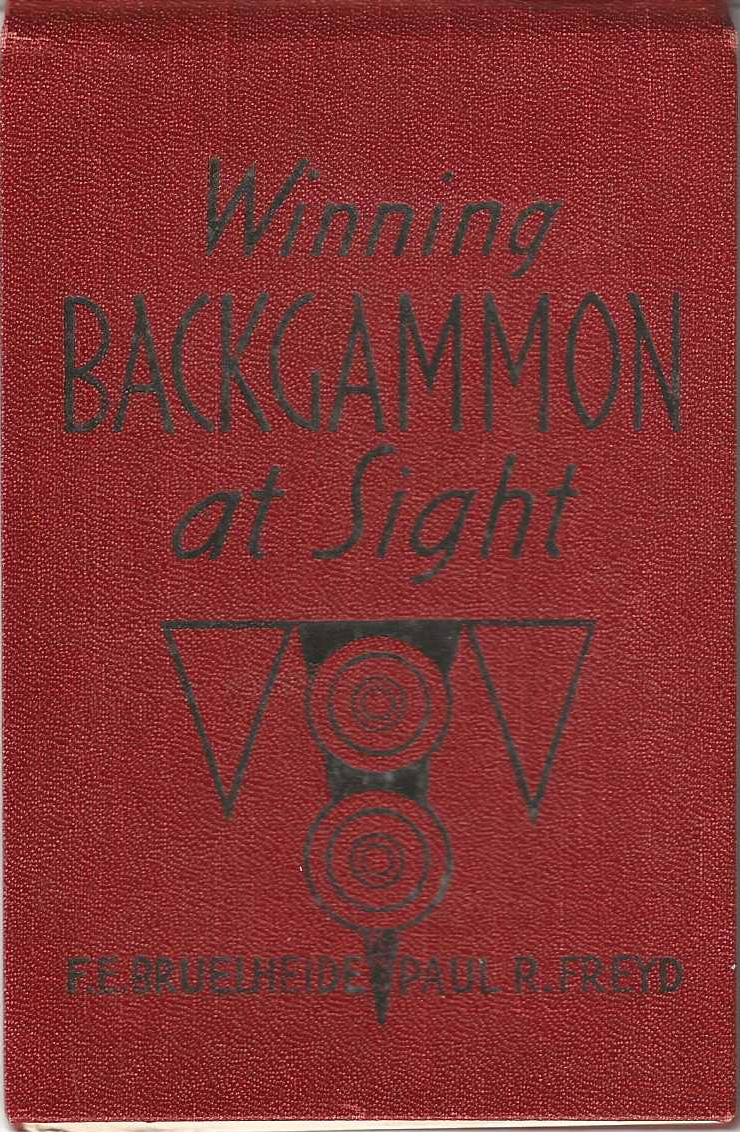

The “At Sight” book series might be viewed as the “. . . for Dummies” series of its day. After the success of “Contract bridge At Sight,” experts Buelheide and Freyd were sought out to lay out the principles of backgammon in an attractive flip-book format. Also included was a fold-out board chart with the opening moves laid out on the field for convenient study, but it seems you had to provide your own checkers.

The “At Sight” book series might be viewed as the “. . . for Dummies” series of its day. After the success of “Contract bridge At Sight,” experts Buelheide and Freyd were sought out to lay out the principles of backgammon in an attractive flip-book format. Also included was a fold-out board chart with the opening moves laid out on the field for convenient study, but it seems you had to provide your own checkers.

Frank Elmer Bruelheide, a prominent bridge expert, hailed from Minneapolis and gave some backgammon lectures at Woodward & Lothrop in Washington D.C. while Freyd offered talks at Marshall Field & Co. in Chicago, showing that while Abercrombie & Fitch in New York may have been the biggest name in 1930 backgammon, there was plenty of professional expertise farther afield.

F.E. Bruelheide also published a tall-format 4-page pamphlet, “Fundamentals of Backgammon,” included in the picture at right, that has been reprinted for use in backgammon sets as late as 1978.

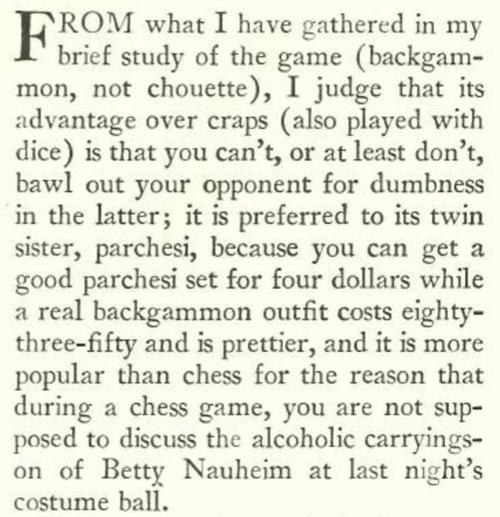

"Tables for Two" (The New Yorker, Oct. 18, 1930)

In “Table for Two,” satirical columnist Ring Lardner turns his gimlet eye on backgammon in an amusing piece that lends detail to our sense of the game’s appeal at the time. The “randomly” selected book that he gently ridicules is The New Backgammon by Elizabeth Clark Boyden. Humorous pieces like this one attest to the very broad awareness the game enjoyed at the time (at least amongst the New Yorker‘s readership) and provide some vivid clues as to the intensity of those early chouettes:

In “Table for Two,” satirical columnist Ring Lardner turns his gimlet eye on backgammon in an amusing piece that lends detail to our sense of the game’s appeal at the time. The “randomly” selected book that he gently ridicules is The New Backgammon by Elizabeth Clark Boyden. Humorous pieces like this one attest to the very broad awareness the game enjoyed at the time (at least amongst the New Yorker‘s readership) and provide some vivid clues as to the intensity of those early chouettes:

When you consider the lack of physical activity and the enormous mental strain that are part of an evening of tric trac, little battle, tables, or whatever you wish to call it, do you wonder that an addict wakes up in the morning so irritable that when her husband mentions his golf date, she barks like a dog?

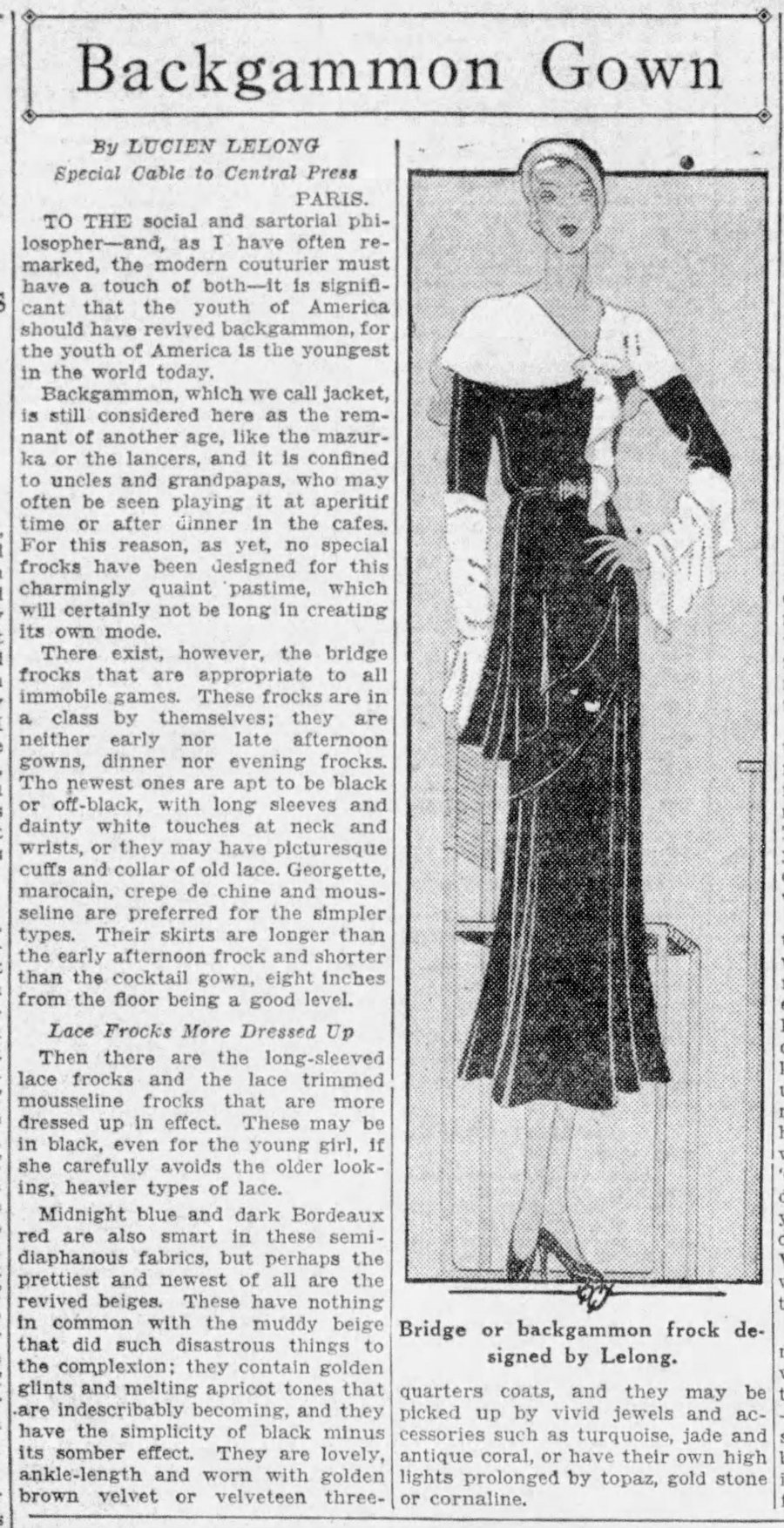

Backgammon Fashions (Oct. 1930 - Feb. 1931)

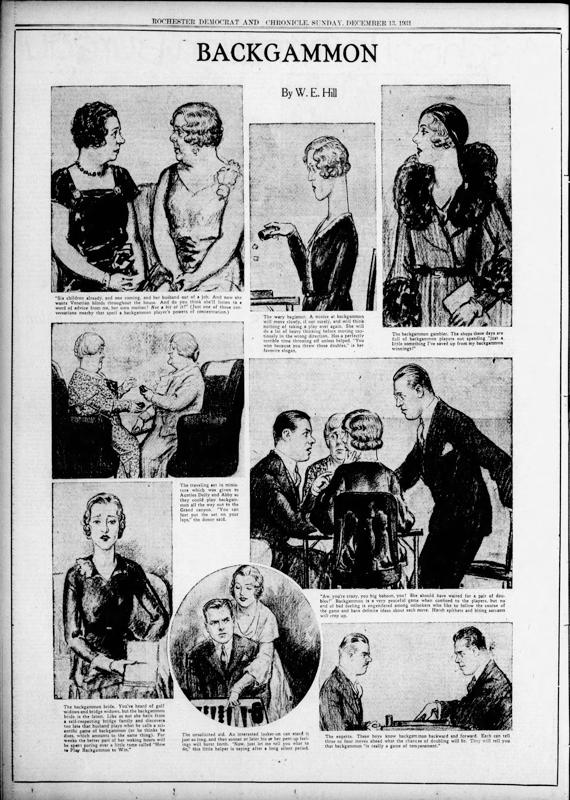

The Belleville News-Democrat, Dec. 13, 1930.

Carson Pirie Scott advertisement, Chicago Tribune, Dec. 13, 1930.

The “backgammon frock” wasn’t a new type of garment, but for about four months overlapping the holiday season of 1930, advertisers renamed their informal party dresses for the game of the moment. Parisian couturier Lucien Lelong credits the revival of backgammon to American youth and notes that the old game has not been revitalized in France — an interesting comment, given that the doubling game and chouette were reportedly originated in French seaside resorts a few years earlier.

The May Company, Los Angeles Evening Express, Feb. 10, 1931.

Some fashion ads of 1930 refer to “backgammon colors” in their descriptions of garments, hats, or handbags, which are sometimes specified as black, red, and white, which would seem to imply those were the dominant checker / board schemes of the time.

Some designers even began working backgammon motifs into their creations, with the iconic triangular board points, circular checkers, and square dice providing plenty of shapes to work with. Backgammon stockings, backgammon purses, and even backgammon pajamas made appearances under Christmas trees in 1930.

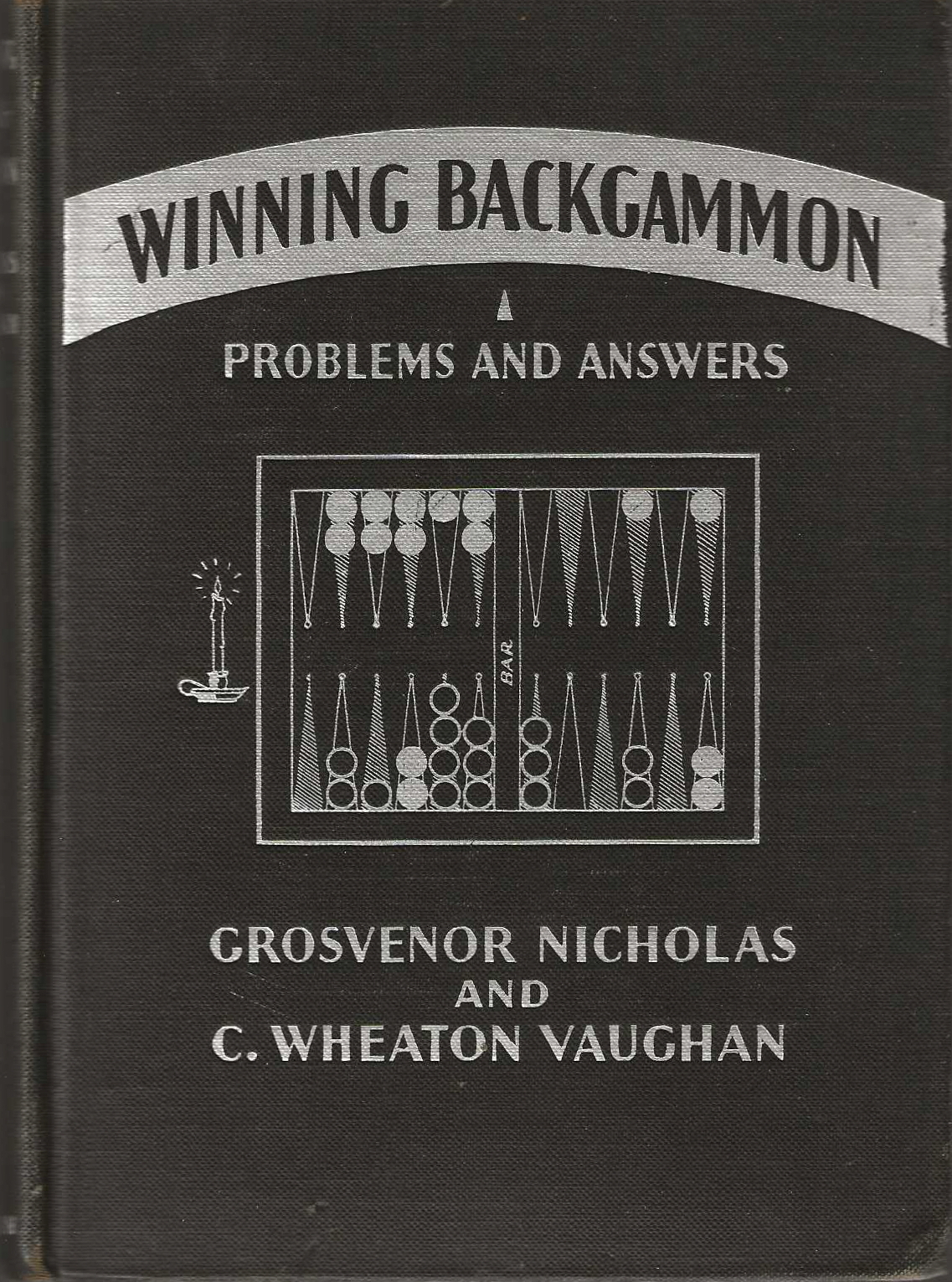

Winning Backgammon (Oct. 29, 1930)

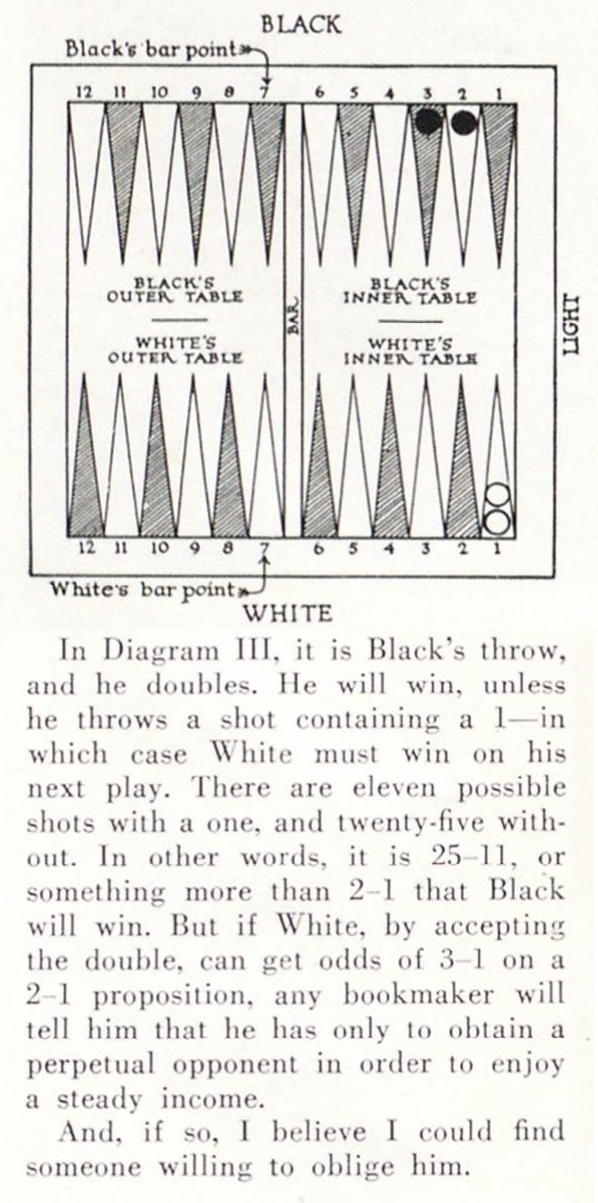

In the midst of a publishing frenzy amongst backgammon experts, Grosvenor Nicholas returns with his second work, in partnership with C. Wheaton Vaughan, and this time achieves another “first”: a book of problems for those already very familiar with the rules and terminology of the game. Each of 23 chapters present a game scenario designed to exemplify sharply defined concepts (bearing off for safety, filling gaps . . . ). While such books have been commonplace since Joe Dwek’s Backgammon for Profit (1975), none has taken Winning Backgammon‘s approach of offering multi-roll sequences to illustrate its concepts. Each “problem” specifies 5-9 rolls for the reader to play out properly, and then offers commentary on the entire exchange, showing the possible consequences of improper play. It’s a very effective approach that should help students familiarize themselves with patterns of play that recur frequently over the table.

In the midst of a publishing frenzy amongst backgammon experts, Grosvenor Nicholas returns with his second work, in partnership with C. Wheaton Vaughan, and this time achieves another “first”: a book of problems for those already very familiar with the rules and terminology of the game. Each of 23 chapters present a game scenario designed to exemplify sharply defined concepts (bearing off for safety, filling gaps . . . ). While such books have been commonplace since Joe Dwek’s Backgammon for Profit (1975), none has taken Winning Backgammon‘s approach of offering multi-roll sequences to illustrate its concepts. Each “problem” specifies 5-9 rolls for the reader to play out properly, and then offers commentary on the entire exchange, showing the possible consequences of improper play. It’s a very effective approach that should help students familiarize themselves with patterns of play that recur frequently over the table.

The book ends with a REVISED version of “The Authorized Rules for Modern Backgammon,” which one might have expected to be the same as the “approved” rule set published in John Longacre’s Backgammon of Today just four weeks prior with a shared copyright between Longacre and Nicholas. But the two rule sets, while not really conflicting on any points of substance, are differently arranged and cover some different ground. (Longacre omits the rule for Doubling, while Nicholas omits any reference to Chouette).

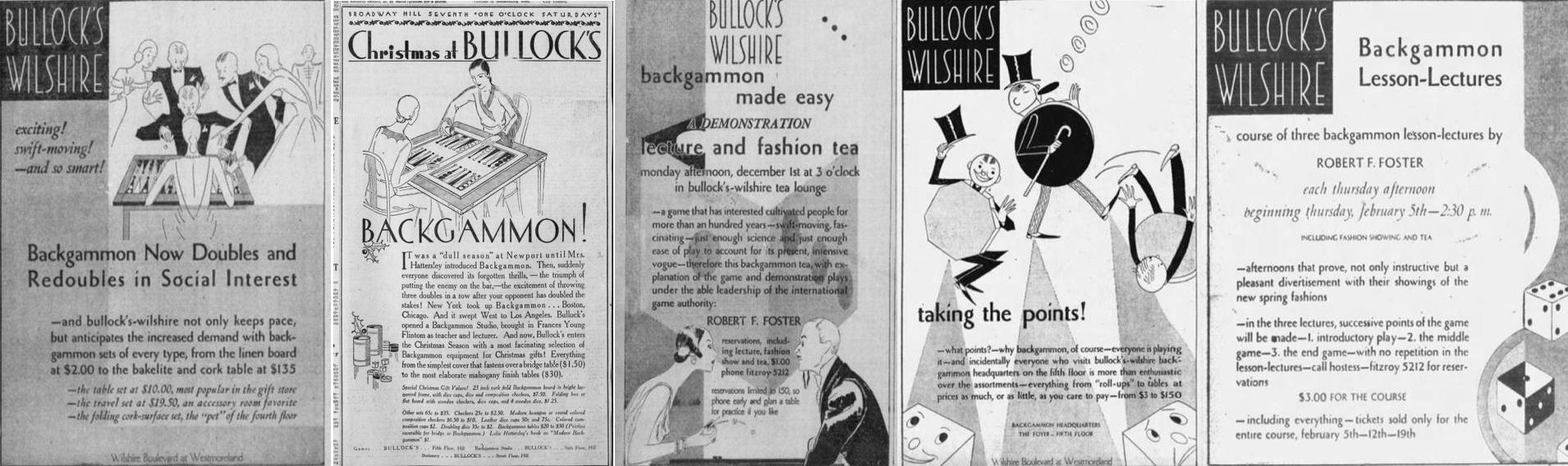

Bullock's Wilshire Advertisements (Nov. 3, 1930 - Feb. 2, 1931)

Bullock’s Wilshire, a magnificent art-deco department store, opened in Los Angeles in 1929 and a year later was promoting its backgammon offerings with a series of richly detailed newspaper ads and expert lectures. Robert F. Foster, not a familiar backgammon name, was a prominent gamesman who wrote a popular edition of Hoyle in 1897 and a variety of gaming books, particularly on bridge. He was also an expert in memory training. There is no reference to his having lived in California in his Wikipedia biography, but he gave lectures at Bullocks in both late 1930 and early 1931, and he is credited in the Catalogue of Copyright entries with having published a pamphlet titled “Backgammon Made Easy” in Hollywood right around this time (see listing at right). Further ads in early 1931 publicize lectures by Frances Young Flintom (featured in the Beachside Backgammon section below) and F. E. Bruelhide, author of Winning backgammon at Sight.

Bullock’s Wilshire, a magnificent art-deco department store, opened in Los Angeles in 1929 and a year later was promoting its backgammon offerings with a series of richly detailed newspaper ads and expert lectures. Robert F. Foster, not a familiar backgammon name, was a prominent gamesman who wrote a popular edition of Hoyle in 1897 and a variety of gaming books, particularly on bridge. He was also an expert in memory training. There is no reference to his having lived in California in his Wikipedia biography, but he gave lectures at Bullocks in both late 1930 and early 1931, and he is credited in the Catalogue of Copyright entries with having published a pamphlet titled “Backgammon Made Easy” in Hollywood right around this time (see listing at right). Further ads in early 1931 publicize lectures by Frances Young Flintom (featured in the Beachside Backgammon section below) and F. E. Bruelhide, author of Winning backgammon at Sight.

The five Bullock’s Wilshire print ads below offer much to interest the backgammon historian: an amusing depiction of a chouette that captures the excitement and drama of the multi-player game, prices on a variety of backgammon boards, a visual reference to the octagonal checkers available at the time, doubling dice priced from $.35 to $2, and an example of the department-store lecture series offered across the country in the years 1930-31. The second ad includes some particulars on backgammon’s spread westward, crediting Leila Hattersley for introducing the game to Newport society, and celebrating Bullock’s hiring of Frances Young Flintom as resident teacher and lecturer.

Bullock’s Wilshire ads from The Los Angeles Times: Nov. 6, Nov. 11, Nov. 27, and Dec. 18, 1930; Feb.2, 1931. Click for a full-size PDF of file of all five ads.

"Backgammon Is the Rage Here" (St. Lous Post-Dispatch, Nov. 17, 1930)

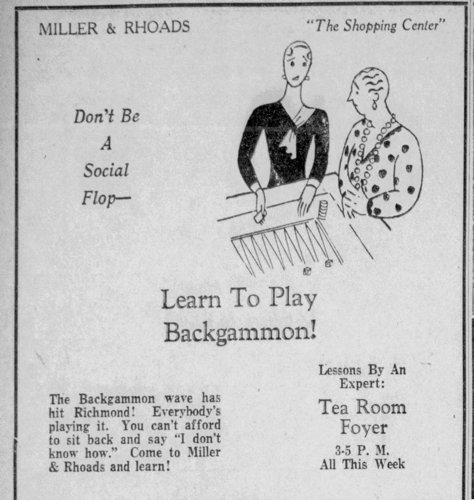

Richmond Times-Dispatch, Dec 10, 1930.

The Social Pages of major cities all around the country are peppered with references to backgammon parties, backgammon lessons, and backgammon fashions. This wonderful extended feature in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch captures the spread of the game from east to west, and conveys something of the stir it caused in traditional gaming behavior in the upper class social circles, where bridge generally reigned supreme. The delightful illustration contrasts a staid elder generation in florid antebellum dress with the jazz-age styles of the younger “smart set” engaged in the raucous give-and-take of a chouette. (Nevermind the illustrator didn’t put enough checkers on the board, or make clear it’s one against five — just look at how well he captures the postures, gestures and expressions of a multi-handed game!)

Playing a competent game of backgammon in 1930 became a fashionable social skill, and the references to backgammon lessons and lectures in this article and in the many newspaper advertisements of the time, such as the one at right, may have been for many something akin to dance lessons: don’t be a backgammon wallflower!

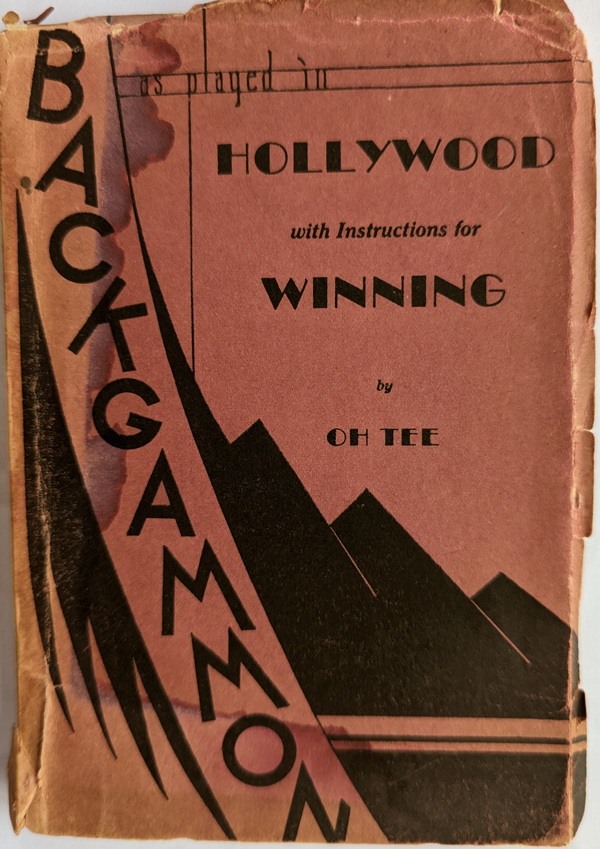

Backgammon As Played in Hollywood (Nov. 20, 1930)

Image: Levy Collection

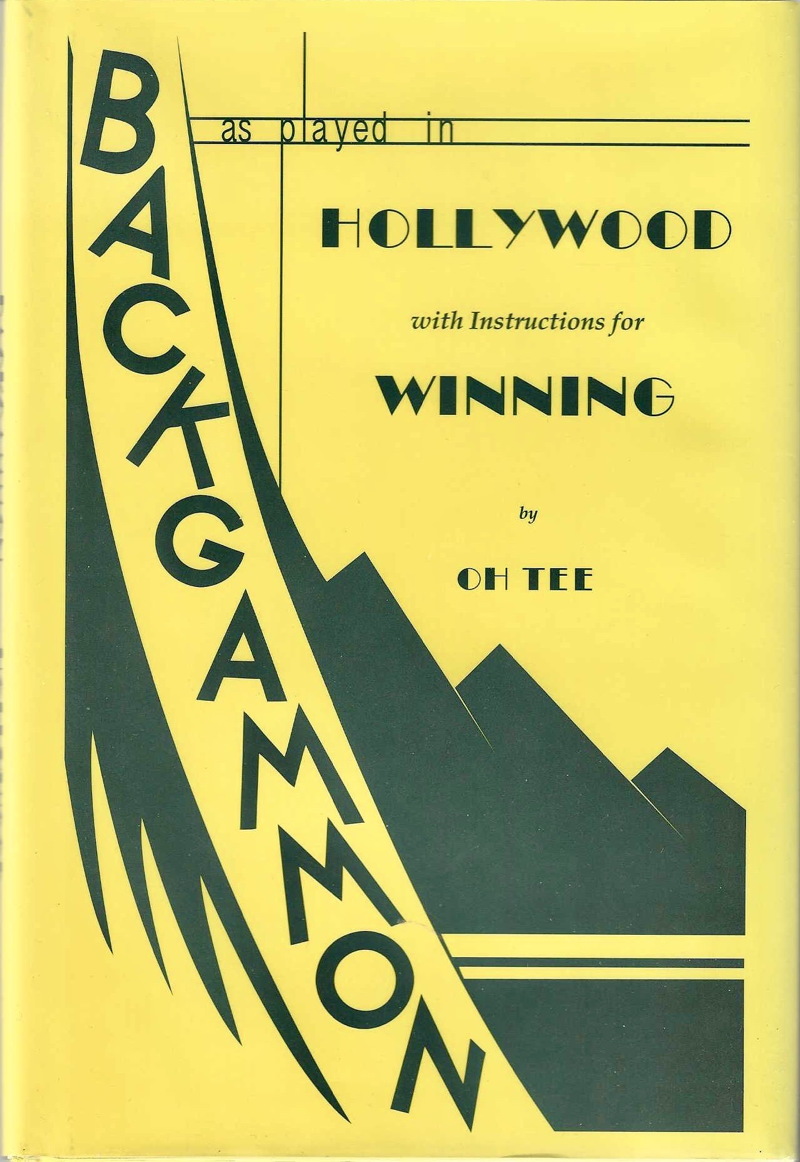

That copies of this obscure backgammon text are available to us is thanks to the initiative of Michigan collector Maurice Barie, who located a microfilm copy of the original at the Library of Congress and re-issued it in a handsome hardcover facsimile edition of 250 copies in 2015 (below right). Only recently has an original copy been discovered in the collection of David Levy, a bibliophile specializing in 18th -19th century gaming literature.

That copies of this obscure backgammon text are available to us is thanks to the initiative of Michigan collector Maurice Barie, who located a microfilm copy of the original at the Library of Congress and re-issued it in a handsome hardcover facsimile edition of 250 copies in 2015 (below right). Only recently has an original copy been discovered in the collection of David Levy, a bibliophile specializing in 18th -19th century gaming literature.

Perhaps the most distinctive aspect of the book is that it is a west-coast production, while all the other backgammon books of the day arose from the east coast or Chicago milieus. It is published under a whimsical pseudonym, “Oh Tee,” which seems likely to suggest the initials “O.T.” despite the overwrought protestation of the publisher’s note at above right.

2015 Facsimile edition.

If there is a “west-coast style” that emerges in the book it is perhaps that “scoring by checkers,” where the damage is figured by the quantity and position of the loser’s remaining checkers, was popular, along with very liberal automatic doubling and scoring options. For instance, any time three sets of doubles in a row emerged during play, the cube level was increased. And when it came to scoring by checkers, each quadrant doubled the point value: 1/2/4/8 rather than 1/2/3/4 points per checker. Backgammon variants such as “deuces wild” also seem to have been popular there, perhaps suggesting a less bookish, more chaotic style of play.

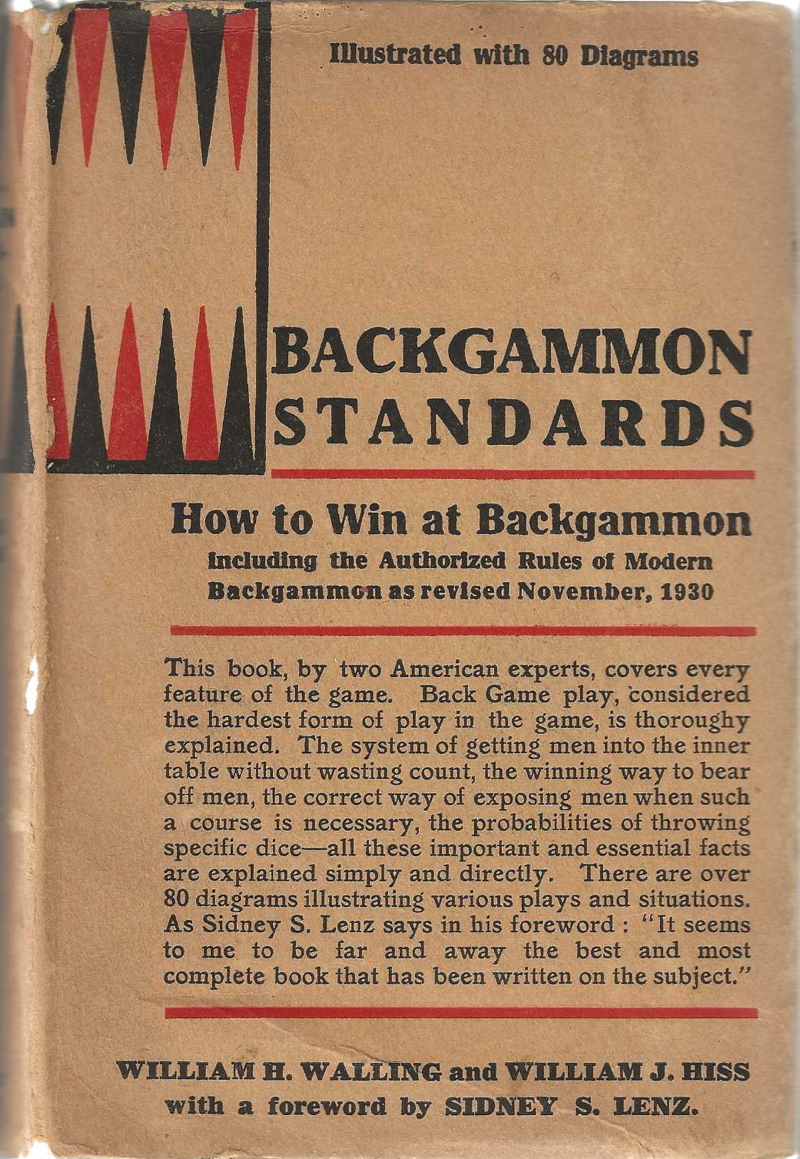

Backgammon Standards (Nov. 26, 1930)

A London printing of the book, 1931.

In a somewhat over-dramatized yarn, the foreword of this book suggests that the co-authors had submitted separate books to the same publisher, who decided to award publication to the winner of a marathon backgammon session lasting several evenings. When the result was a tie, they decided to merge the two efforts into a single book. The truth seems a bit less sensational, as the two writers apparently converged on Simon & Schuster at an opportune time, played some backgammon over lunch and agreed to knock out this book together. A detailed account of this collaboration appears in the publisher’s Inner Sanctum column in Publishers Weekly, at right.

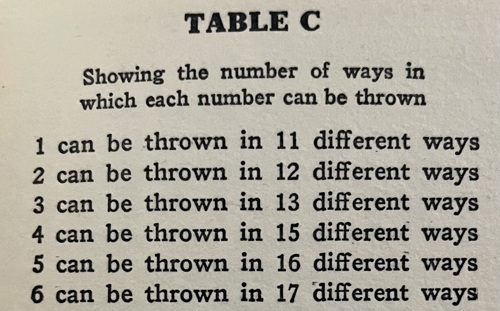

The account gives an impression of haste. The prominent publishing house perhaps felt an opportunity passing them by with so many other imprints cashing in on backgammon books. The arrangement of concepts in some broadly-themed chapters (“General Theory of Play,” “Advanced Strategy,” “Losing Plays”) is haphazard, and it seems no competent player reviewed the table of odds for hitting checkers at different distances — two of the figures in ‘Table C’ are wrong.

A few of the Williams’ wordings are notable. In commentary on Diagram 42, they may be the first to use the term “split” in describing back men on separate points: “The 5 point in the opponent’s table is very valuable and it is frequently wise for the player to break his men in the adversary’s inner table, as when they are split the possibility of making this 5 point is greatly enhanced.” And on the previous page they share a quaint bit of lost terminology that would be fun to bring back, if only facetiously: “One of the least valuable points on the board is the adversary’s bar point, which is frequently referred to as the booby point. It is a hard point from which to escape under usual circumstances.”

Easily the most intriguing part of the book is their treatment of the Back Game, because after offering some a general strategic advice they offer several specific examples followed by a transcription of an entire sample game. It’s a rather stolid 1-2 backgame with no recirculation of checkers, but does reveal some telling blind spots of the day. Here is a transcription of the game that you can drop into XG to review, or play out by hand.

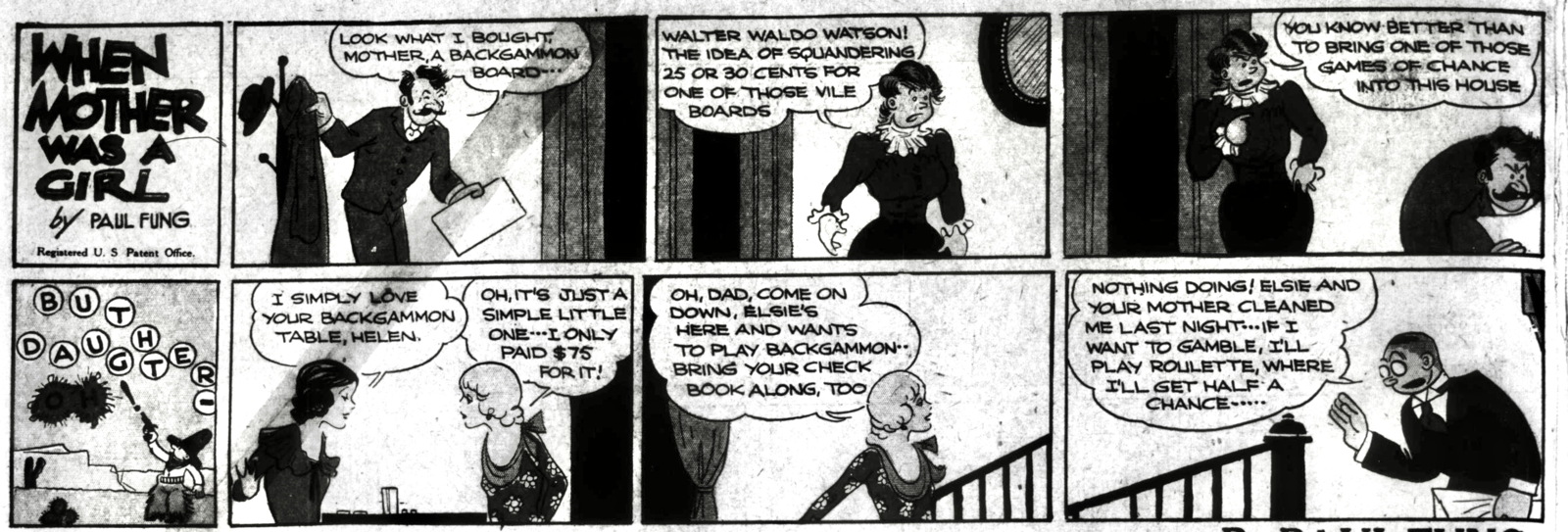

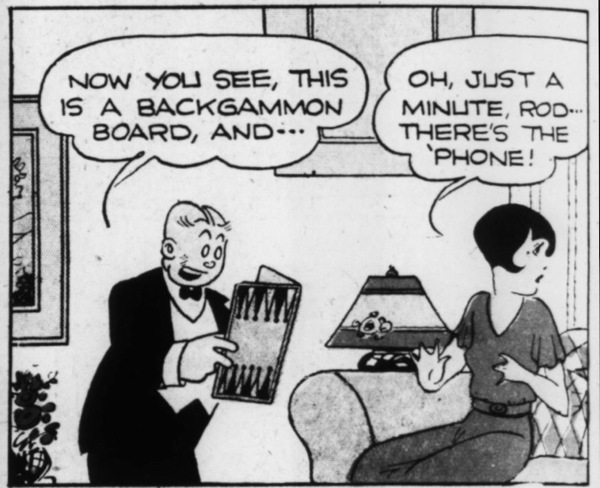

When Mother Was a Girl (Nov. 30, 1930)

The premise of this strip was to contrast the staid and proper habits of the older generation with the reckless independence of women in the roaring 20’s. The bottom left panel always reads “But Daughter — Oh!” (difficult to discern here). The extravagant cost of modern backgammon tables, instruction, and of course losing was a frequent topic in humorous treatments of the day. Cartoonish Paul Fung returns to backgammon in his other popular strip Dumb Dora, the following spring.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 30, 1930.

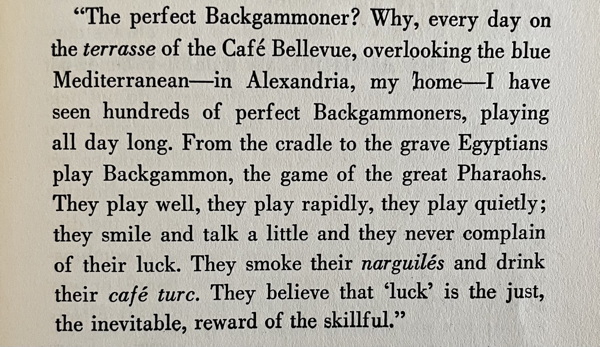

"The Perfect Backgammoner" (Vanity Fair, Nov. 1930)

Julian Jerome quotes Georges Mabardi in this passage a month before Mabardi’s book hit the shops.

It’s time that Julian Jerome got credit for this delightful article, which was promptly re-printed under Clair Boothe Brokaw’s name at the end of Georges Mabardi’s Vanity Fair’s Book of Backgammon just a month later, and again when the book was re-issued in 1974. Taking etiquette as his subject, Jerome offers a colorful gallery of “backgammon nuisances” plaguing the drawing rooms of the day: the lazy player, slow player, cup rattler, fast shooter, school-teacher, point-counter, cock-dice thrower; the grouser, the chortler, the coaxer — the obnoxious doublers and the kibitzers. Similar characters would be satirized in various publications of the 1970’s-80’s, but it’s great fun to see these familiar and timeless types expressed in the style of the 1930’s.

After all the hilarity, though, the piece closes with an atmospheric celebration of backgammon cool, expressed by Georges Mabardi in Hemingway-inflected prose.

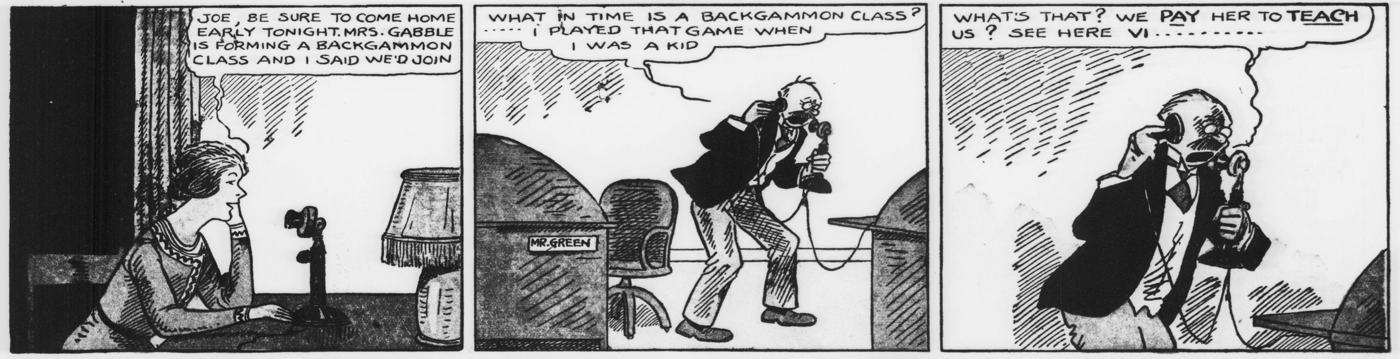

Mr. and Mrs -- (Nov. 30, 1930)

A nebbishy, aging gentleman suffering the indignities of a spouse’s blithe demands was a popular comic trope of the day. In their role as social hostesses, women were major drivers of the backgammon boom, and wifely enthusiasm for backgammon is a recurring gag in period humor such as this full-page installment of Mr. and Mrs–. Click on the comic strip below to view the entire page!

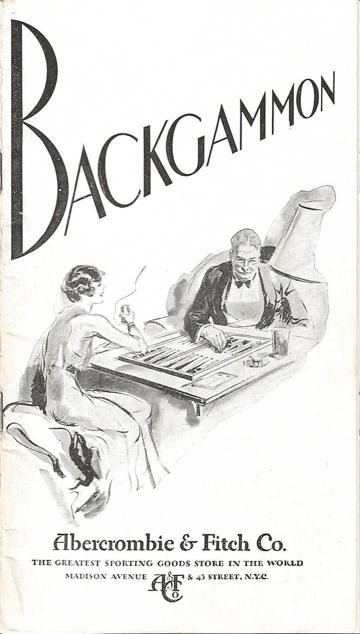

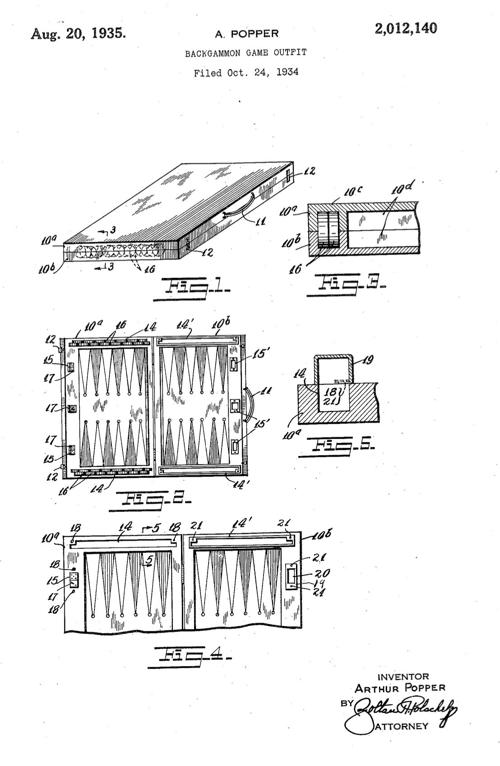

Abercrombie & Fitch Catalogue (ca. Dec. 1930)

This pamphlet begins with the J.S. Ogilve ‘How to Play Modern Backgammon’ material described above, and then provides 4 pages of Abercrombie & Fitch backgammon equipment. A&F magazine ads for similar items appeared in September-November of 1930 with no mention of doubling cubes, while the final page of this pamphlet includes a notable photo of one. (A photo of the actual A&F cube can be seen here).

It is interesting to note that all of the checkers in the catalogue appear to be wooden. Bakelite checkers perhaps appeared the following year.

The illustration on the cover had appeared on September 19th in a full-page New Yorker advertisement (at right), and conveys the idea that backgammon is being taken up by a new, youthful generation as well as the older set. Note that while the ad celebrates doubling, it does not advertise a cube for sale, and neither did another one in the November issue of Vanity Fair. In the December 13, 1930 issue of The New Yorker, a notice of a set whose “counter, dice, and doubling block fit into a long leather tube,” with dice cups that fit over the ends “so they won’t rattle about.” This would appear to match the picture of a set featured in these other ads, but without the cube.

"The Official Laws of Backgammon" (Vanity Fair, Dec. 1930)

There are notable omissions in Jerome’s list of support for his proposed rules.

It is remarkable how many different “Official” sets of rules were published in 1930. Each one cites for authority some assortment of the same named private clubs and published authors on the game — yet no two sets is the same. This article is unique among them as it presents the laws as in a state of negotiation, though “substantially in force at many fashionable clubs whose members play according to the rules in this article.” The near-dozen clubs Julian Jerome mentions does not include the influential Racquet and Tennis Club of New York City, which would take leadership in codifying and publishing the Laws of Backgammon the following year with Charles Scribner’s Sons (1931). Neither does the article make any reference to John Longacre, whose “Authorized” Rules of Backgammon were already in wide circulation (see publications earlier in the timeline, above). Jerome names Thorne, Hattersley, Boyden, Bond, and Mabardi as approving the Vanity Fair rules — an impressive cadre of published writers, but notably lacking backgammon heavyweight Grosvenor Nicholas as well as Longacre. Both, along with Nicholas’ writing partner C. Wheaton Vaughan, would serve on the New York Committee establishing the 1931 Laws.

Jerome’s article is valuable because it discusses some of the points of contention among authorities, even acknowledging disagreement within the Vanity Fair camp. While many competing rules address external protocols or proprieties of play, Jerome’s list includes a major variation in backgammon itself: 12. In bearing off, the higher number of the throw must be played first. Jerome names Georges Mabardi as the chief proponent of this standard, as well as of a more exacting rule governing checker play: “A man touched must be played, if possible.” It seems Mabardi lacked support for these measures, as neither would be included in his own set of “Authorized laws of 1931” published the very same month in Vanity Fair’s Backgammon to Win. Jerome allows such a rule might elevate the formality of backgammon, but cites the “enormous and obvious difficulty in enforcing it . . . [and which] by being constantly broken, would bring all the other laws of Backgammon into disrepute.”

Jerome includes a few other rules that would be subsequently nixed, including a clearly stated “Legal Moves” policy: 10: “If a player [makes an illegal play] his opponent must require the move to be corrected before another throw of the dice is made; otherwise the error stands…”. The corresponding passage in Mabardi would read “. . . the opponent may, at his option, and before he has thrown, demand that the error be corrected.” Also soon rejected was 14: If at any time after the game has begun, it is discovered that the men have been incorrectly set up, play ceases, and that game is declared void.

Competitive play in 1930 was a largely insular, “intramural” activity where the contest for a Club Champion in New York needn’t agree with a corresponding contest in Boston, and the occasional inter-club competitions might simply follow “home court rules.” But there was clearly a desire for more uniformity, at least partly in the interest of elevating the stature and seriousness of backgammon, which remained in the shadow of bridge and chess in terms of public respect. As Jerome mentions, many players of the day regarded backgammon as just “for fun.”

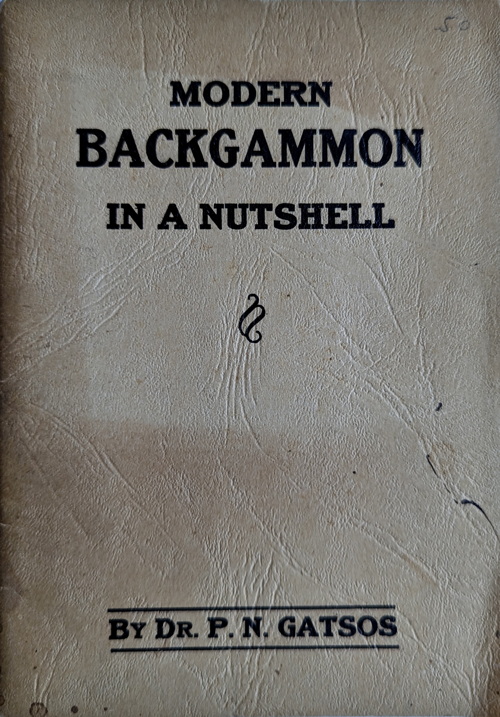

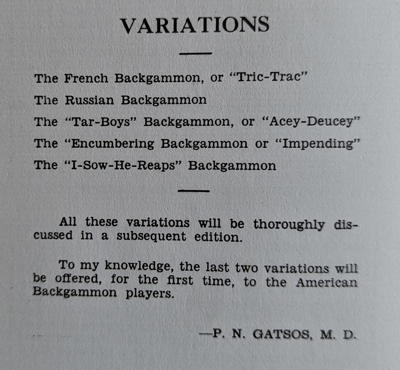

Backgammon In a Nutshell (Dec. 10, 1930)

Image: Levy Collection

Image: Levy Collection

Another self-published treatise on the game, written by a Greek player in Cleveland. This book’s extreme rarity is probably explained by its being circulated in the very small quantities typical of a vanity press. It’s an idiosyncratic book, mixing its titular nutshell metaphor with the subtitle “Backgammon as a Military Conflict.” Gatsos takes Leila Hattersley’s playful martial descriptions of the fifteen checkers to a tedious extreme. Players are “Captains” of their four uniformed squads of checkers; the bar is a hospital to which “wounded men” repair when hit; the entire point of the game is to “obtain information” about the enemy position and bring it safely home; each Captain “also has in his possession a gun with two bullets” — yes, the dice. Like Georges Mabardi, Gatsos numbers the points of the board in the reverse manner to how we do it today, which he identifies as the “only correct method,” used in Europe and the Orient.

Perhaps most tantalizing is a list of backgammon variations printed on the final page to be addressed in a subsequent volume that never seems to have materialized. We can only guess how one might have played “I-Sow-He-Reaps” backgammon.

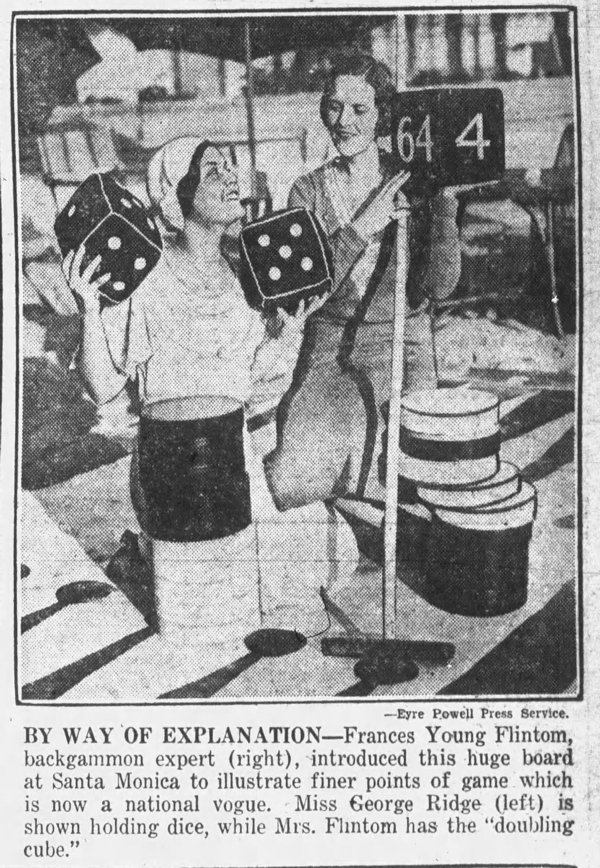

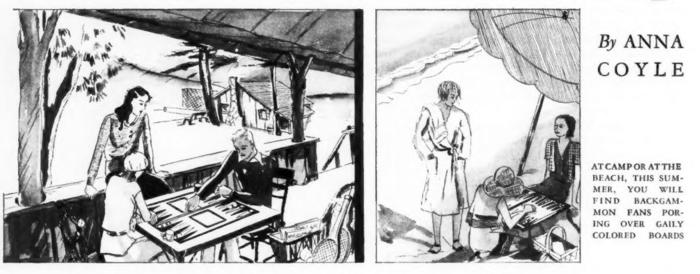

Beachside Backgammon (Dec. 12, 1930)

“The revival of backgammon leads members of the Miramar Club in Santa Monica, California, to invent a beachside version of the game.” New York Journal American, Dec. 12, 1930.

California Daily News, Dec. 17, 1930

Larger-than-life ‘beachside backgammon sets were all the rage at exclusive resorts in Florida, Long Island, and California in late 1930 and early 1931. The sets featured pillowy cushions for checkers and dice, big croupier sticks for moving them around from the perimeter, and what may stand as the largest doubling cube on record! Five further photographs of the Miramar scene at right can be found on the Huntington Library website.

These oversized tables were also ideally suited for instruction, and used for this purpose by Frances Young Flintom, a reputed east coast player who seems to have gotten around the country spreading the backgammon gospel to hostesses desperate to learn the year’s essential new party game: “Mrs. Flintom is given credit for the revival of and intense interest in this game on the west coast, having introduced it in a series of social lectures in Hollywood and los Angeles.” (from Long Beach Press article at right). The Huntington Library photos as well as the published photo at upper right all star Mrs. Flintom holding court during the events publicized in that article.

While the proud history of men-only “club” backgammon has been handsomely celebrated in the Union Club’s Dice Cubes, and Gentlemen (2018), the enormous influence and avid participation of women in popularizing backgammon in the century’s first boom has largely escaped notice. Many of the all-female audience in attendance at these events were women eager to learn the game so that they could host fashionable backgammon parties, which in turn motivated partygoers to achieve a decent mastery of the game.

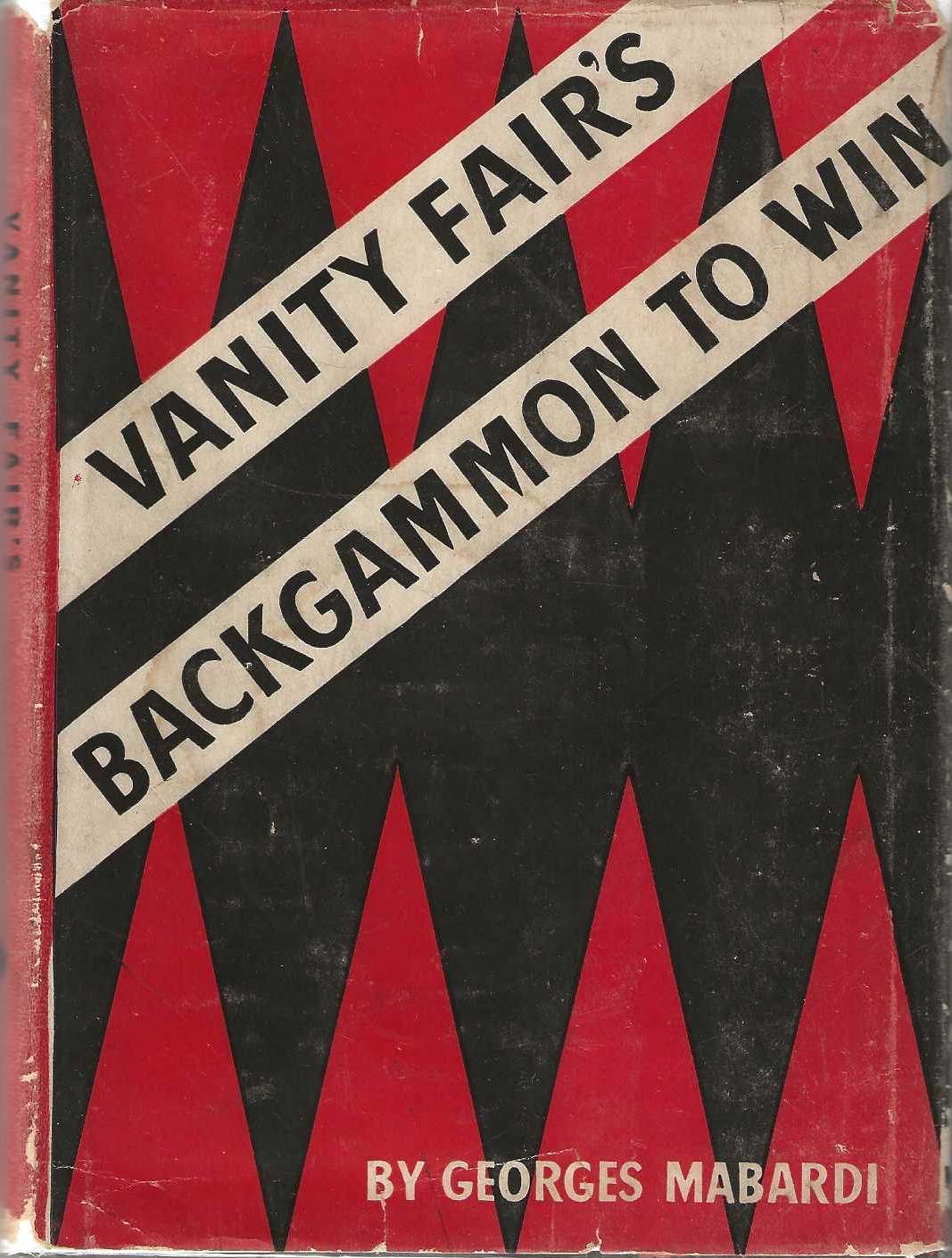

The Vanity Fair Book of Backgammon (Dec. 12, 1930)

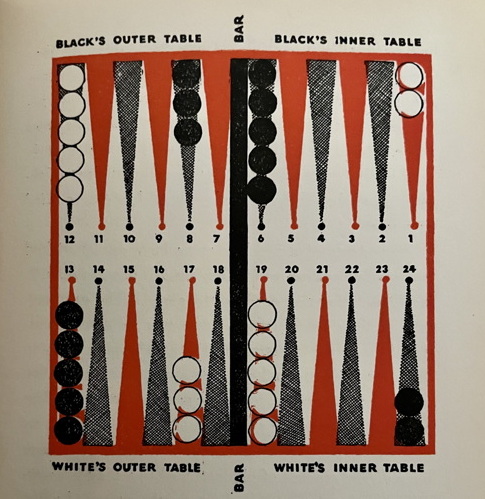

Mabardi numbers the points in the reverse of our usual order, illustrating the unacceptable risk of slotting your 5-point: 20 points of progress. (p. 113)

Although Vanity Fair‘s brand was all about modern life and style, this book reads as a manifesto against the “Modern” inception of the game. Georges Mabardi, Egyptian by birth, held that the ancient game of backgammon had been completely mastered long before 1930 and that neither the Chouette nor the new mania for Doubling had contributed anything new or useful to the game, but had rather corrupted it for reckless thrills.

Although Vanity Fair‘s brand was all about modern life and style, this book reads as a manifesto against the “Modern” inception of the game. Georges Mabardi, Egyptian by birth, held that the ancient game of backgammon had been completely mastered long before 1930 and that neither the Chouette nor the new mania for Doubling had contributed anything new or useful to the game, but had rather corrupted it for reckless thrills.

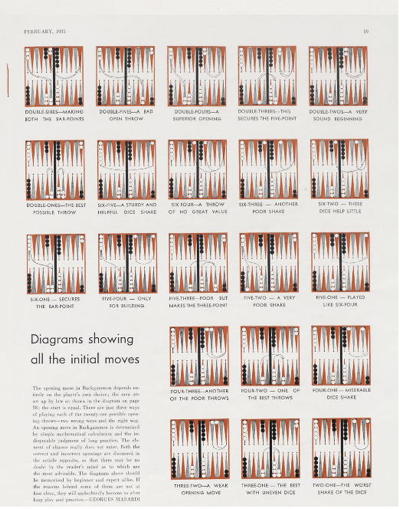

Mabardi’s conception of the game is fascinating and conveyed with style, clarity, and most of all, complete conviction. (Perhaps only Bruce Becker has written with such dismissive certainty.) He presents the player as a military commander withdrawing his troops from the field: “backgammon is always a game of retreat, never of advance” (p.31). Accordingly he stresses the primacy of getting the stragglers (for him, the forwardmost) checkers moving first, and the foolishness of exposing the checkers to risk when they are close to home. Alone among writers in 1930, he absolutely eschews slotting the 5-point on the opening roll, and advances both back men with a host of rolls (64, 63, 62, 43, 41, 32). It is a distinctly Middle-Eastern style that must have seemed exotic to American competitors trained on earlier books of the day. Mabardi views reckless play in the opening as leading modern players to pursue too many back games, which he strongly abjures when playing a skilled opponent who knows how to counter it, a view that would be vindicated over time. Vanity Fair published Mabardi’s “Backgammon Openings” in the February 1931 issue, with a nice 1-page illustration of his preferred moves and some variations in his discussion of them.

Like Longacre before him, Mabardi betrays an imperfect understanding of the risk-reward proposition of doubling: “If two absolutely perfect players engaged in a match, there would never be an accepted double. . . . The author’s chief objection to the double is precisely this — its only raison d’etre is the incompetent play of those who use it.” (p.121) One gets the sense Mabardi may have been no fun at backgammon parties.

The book includes a delightful chapter on “The Etiquette of Backgammon,” unfairly credited to Clare Boothe Brokaw (later Luce, the noted ambassador to Italy) when it is merely a reprint of the Julian Jerome article, “The Perfect Backgammoner,” published the previous month (see above). It seems that, if anything, Brokaw might only have been responsible for the amusing list of “Axioms for Backgammoners to Grind” on the final page.

Also of interest for the backgammon historian is yet another set of “Authorized Rules for 1931” apparently derived from the same drafts that yielded Longacre’s copyrighted set but here explicitly approved by five prominent clubs across the country including the Racquet and Tennis Club of New York. We see that Mabardi conceded his personal preference on several rules conveyed in the Julian Jerome article in the Vanity Fair‘s December issue. Mabardi offers useful commentary on some of the rule variations, and rationales for their adoption. His exposition of chouette and tournament formats is also rich in detail.

Also of interest for the backgammon historian is yet another set of “Authorized Rules for 1931” apparently derived from the same drafts that yielded Longacre’s copyrighted set but here explicitly approved by five prominent clubs across the country including the Racquet and Tennis Club of New York. We see that Mabardi conceded his personal preference on several rules conveyed in the Julian Jerome article in the Vanity Fair‘s December issue. Mabardi offers useful commentary on some of the rule variations, and rationales for their adoption. His exposition of chouette and tournament formats is also rich in detail.

The graphic design of Backgammon to Win makes it the most attractive book of the period. As a Condé Nast project, it exudes fashion-magazine glamor, featuring a bold cover and end-paper scheme, artful board diagrams, and charming illustrations of backgammon accessories: martinis, cigarettes, canapés.

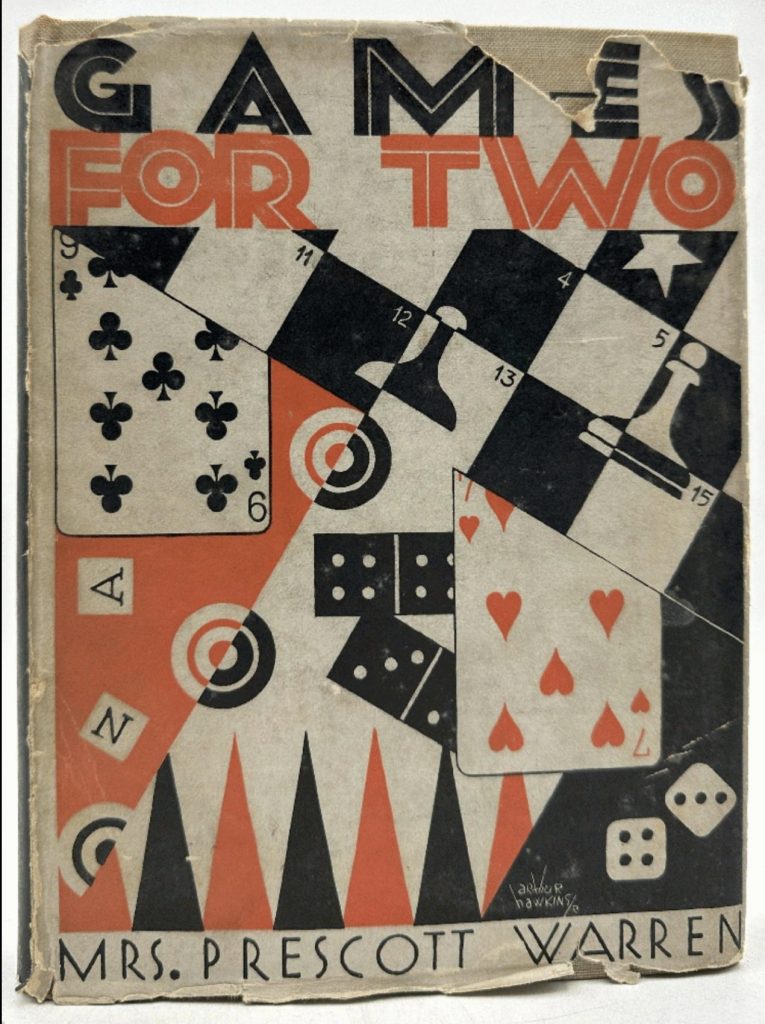

Games for Two (Dec. 18, 1930)

Image: internet

Emily Stanley Warren, or “Mrs. Prescott Warren” as she styled her name for her several publications, was another bridge expert who diverted her attention to other games such as Mahjong and, here, fifteen games to be enjoyed by pairs of players. The twenty-five pages she devotes to backgammon include some interesting reflections on the game’s appeal (“a marvelous opportunity for polite gambling”), while affirming that it serves only as a distraction from “that game of all games, Bridge.”

In a passage about doubling, Warren mentions that in order to keep track of the stakes, “Backgammonists use two-inch cubes which indicate these doubles,” which while not strictly accurate (cubes of the day generally fell between 1.25-1.5″), does convey the generous dimensions of these early cubes compared to the smaller .75-1″ size cubes that would become more common in the ensuing decades.

Warren provides the obligatory chart listing the odds of hitting blots at various distances, and like others she errs in counting — in this case, suggesting only one way of hitting a checker 12 pips away rather than 3.

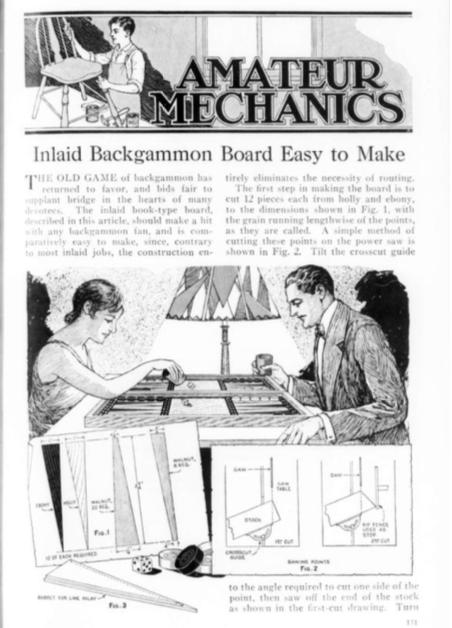

"Inlaid Backgammon Board Easy To Make" (Popular Mechanics, Jan. 1931)

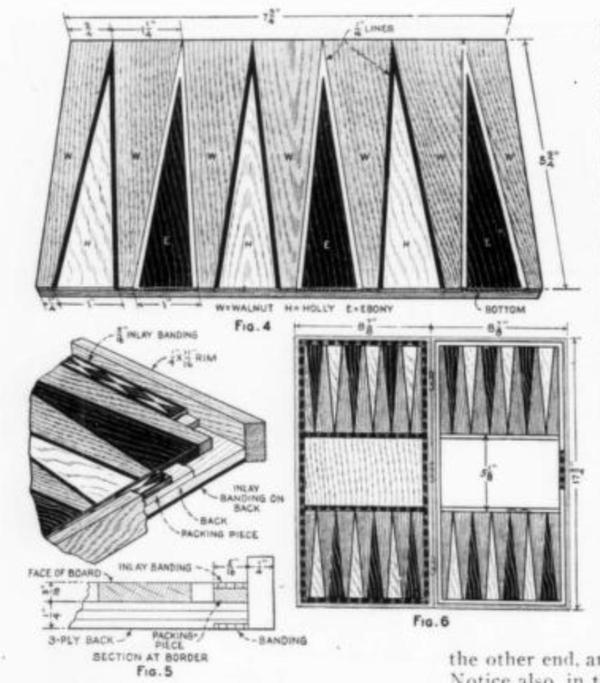

From Popular Mechanics, Jan. 1931

Even Popular Mechanics magazine got in on the backgammon craze with this detailed article on how to construct an inlaid backgammon table out of walnut, holly, and ebony woods. The piece is accompanied by a charming illustration of a couple at play, ignoring the tradition of bearing off toward the light.

Human Backgammon (Jan. 1931)

Los Angeles Daily News, Feb. 2, 1931

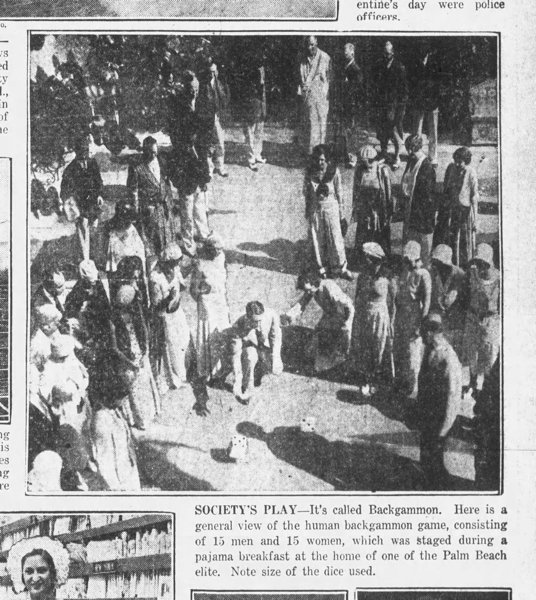

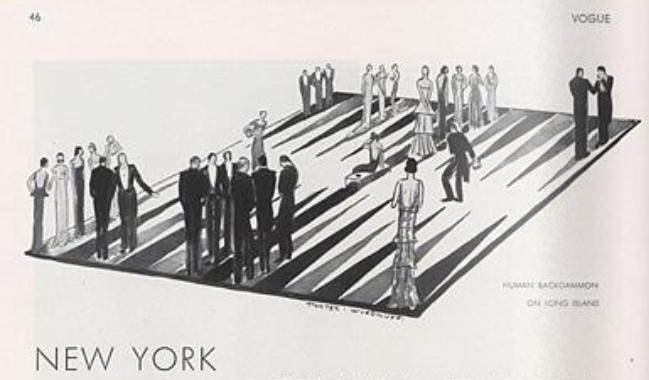

Not to be confused with the “giant backgammon” popular at beachside resorts, “human backgammon” was a party novelty where guests themselves became checkers. the January 1931 issue of Vogue included the illustration at right, along with an account of an “Animated backgammon party” given by Mrs. William Randolph Hearst at a Long island Party, presumably sometime in November of 1930 given the timeline for preparing and publishing magazines. Differentiating the two sides of men and women in a human backgammon game would have been made easier by the men’s uniformly black dinner jackets.

Not to be confused with the “giant backgammon” popular at beachside resorts, “human backgammon” was a party novelty where guests themselves became checkers. the January 1931 issue of Vogue included the illustration at right, along with an account of an “Animated backgammon party” given by Mrs. William Randolph Hearst at a Long island Party, presumably sometime in November of 1930 given the timeline for preparing and publishing magazines. Differentiating the two sides of men and women in a human backgammon game would have been made easier by the men’s uniformly black dinner jackets.

Accounts of a similar party being thrown by Chicago/Detroit socialites Mr. and Mrs. Charles M. Hall at their villa in Palm Beach, Florida on January 31st were splashed across Society pages of newspapers across the country.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Feb. 7 (left) Feb. 2 (middle), Jan. 30 (right), 1931

"In New York" with Gilbert Swan (The Peninsula Times Tribune, Feb. 4, 1931)

Gilbert Swan returns to backgammon in early 1931, reflecting on the state of the fad and another up-and-coming board game, Camelot. Midway through he makes an interesting comment about the scope of backgammon’s popularity: “Backgammon has been taken up particularly by the society folk, being more fashionable — at least to date — than universally popular. It is being “done” almost everywhere among the “who’s who,” gradually gaining fans among the great ‘general public.’ This observation is in keeping with the tone and content of virtually every book, article, and illustration included on this web-page chronicling the 1930’s boom.

Gilbert Swan returns to backgammon in early 1931, reflecting on the state of the fad and another up-and-coming board game, Camelot. Midway through he makes an interesting comment about the scope of backgammon’s popularity: “Backgammon has been taken up particularly by the society folk, being more fashionable — at least to date — than universally popular. It is being “done” almost everywhere among the “who’s who,” gradually gaining fans among the great ‘general public.’ This observation is in keeping with the tone and content of virtually every book, article, and illustration included on this web-page chronicling the 1930’s boom.

None of this is to say backgammon didn’t enjoy increased popularity among the general public at the time, but the lack of evidence outside the “society pages” and elite publications does suggest the real mania for the game occurred mostly among the very wealthy.

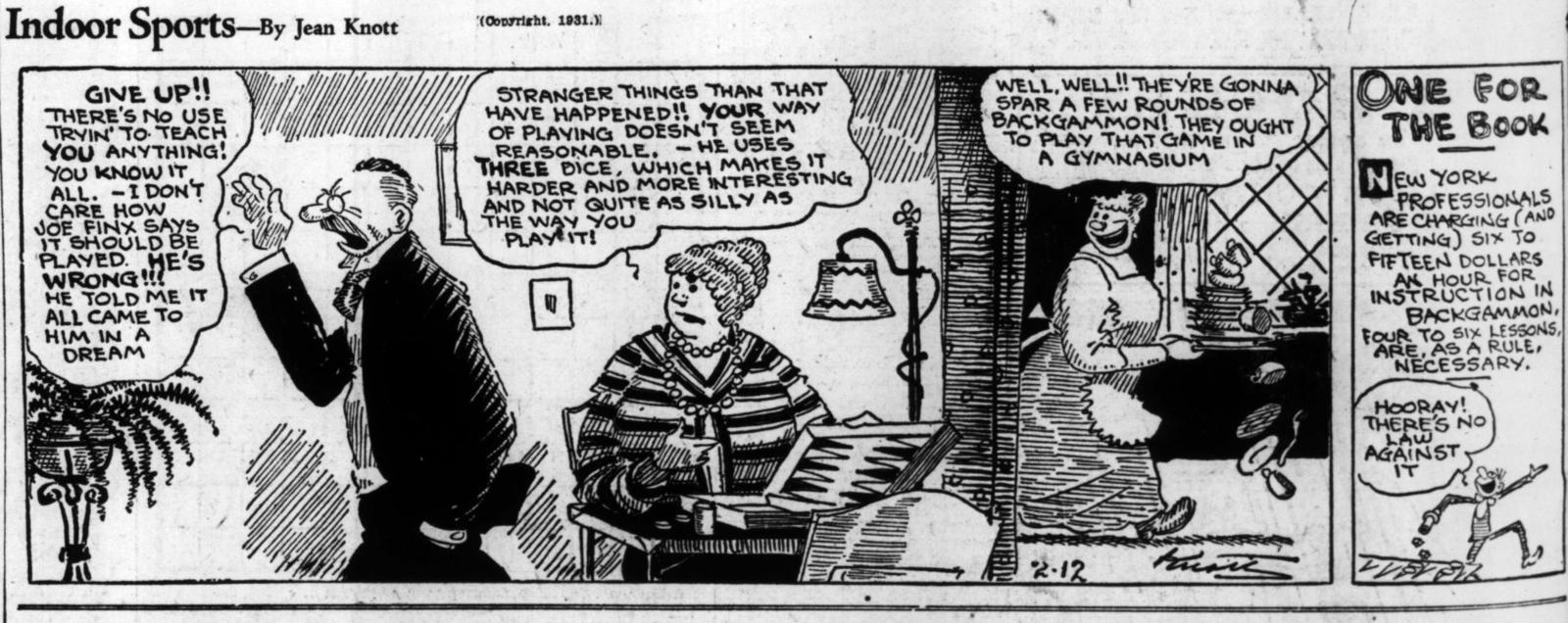

Indoor Sports (Feb. 12, 1931)

If the last frame of this cartoon can be taken at face value, the New York teaching rate was somewhere in the $100 – $300 per hour in 2023 dollars.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 12, 1931.

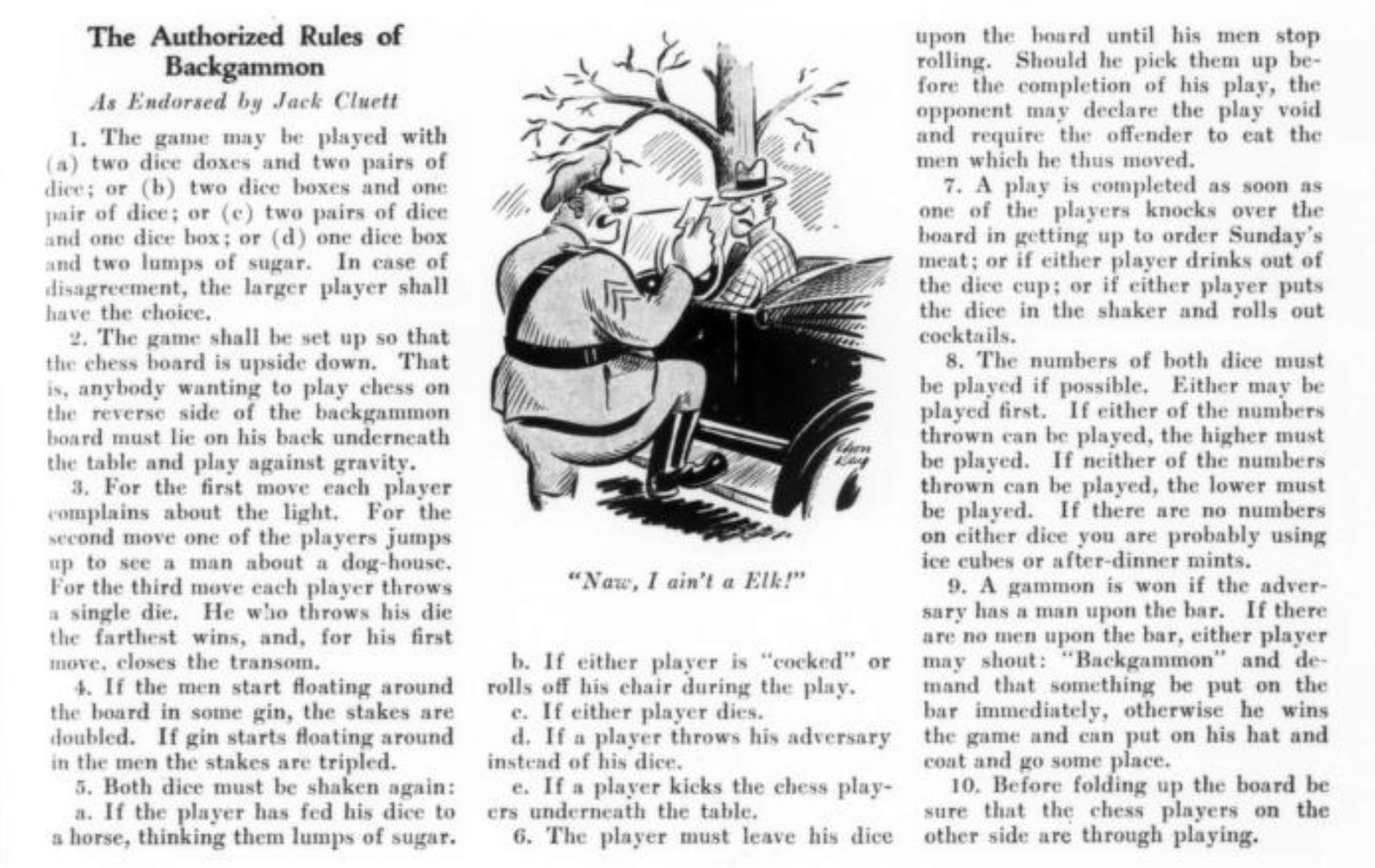

"The Authorized Rules of Backgammon" [Parody] (Feb. 14, 1931)

Jack Cluett contributed humorous pieces to backgammon-savvy magazines Vanity Fair and The New Yorker, but this satiric take on the many “authorized” rules sets promulgated at the time was found in the cartoon / humor magazine Judge. The humor comes across best if imagined in the voice of Groucho Marx.

Judge, Feb. 14, 1931

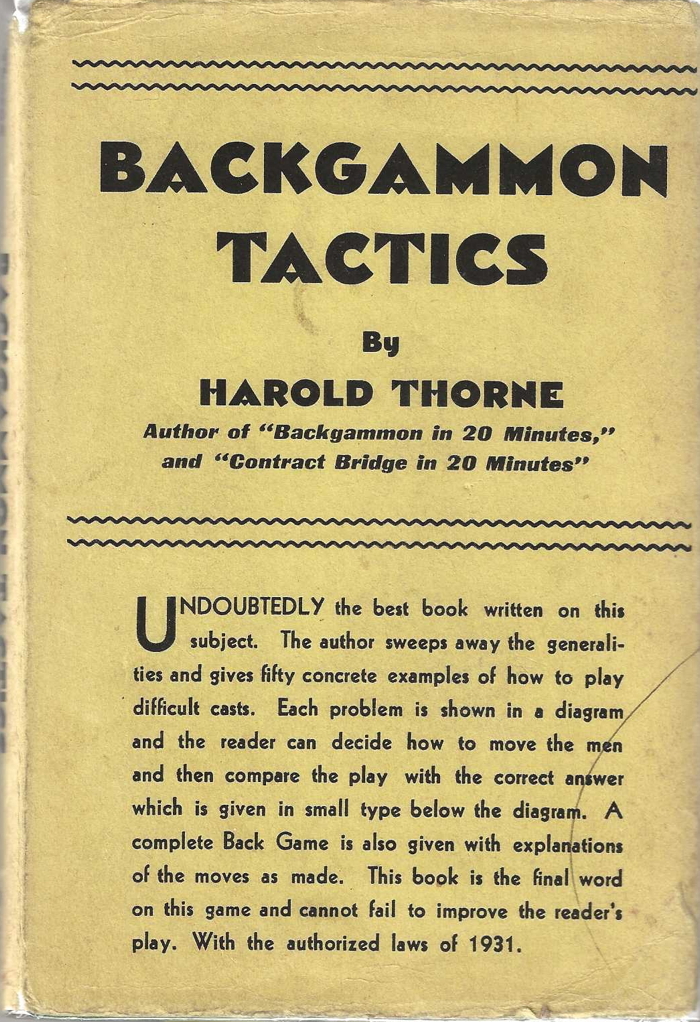

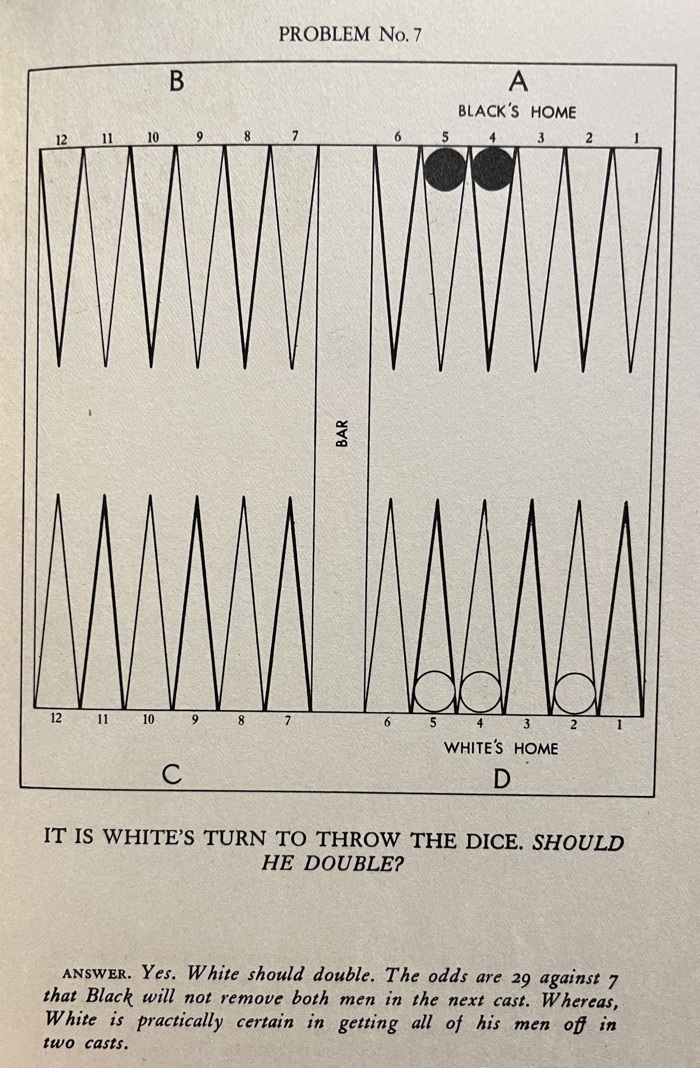

Backgammon Tactics (Feb. 17, 1931)

Harold Thorne returns to the field, following up Backgammon in 20 Minutes from the previous summer with this book of 50 problems. As with the previous year’s problem book, Winning Backgammon, it is the omissions that provide the most insight into the state of expert play at the time. A broad omission in approach is that the solutions are explained without any attempt to articulate a memorable principle that could be used in similar situations. Very frequently, the most interesting aspect of a position goes unmentioned.

Harold Thorne returns to the field, following up Backgammon in 20 Minutes from the previous summer with this book of 50 problems. As with the previous year’s problem book, Winning Backgammon, it is the omissions that provide the most insight into the state of expert play at the time. A broad omission in approach is that the solutions are explained without any attempt to articulate a memorable principle that could be used in similar situations. Very frequently, the most interesting aspect of a position goes unmentioned.

For instance, Position #7 (at right) has the distinction of being the very first cube action problem ever published. However, only the offer is in question; the more difficult take/drop decision isn’t even acknowledged. Thorne calculates Black’s chances of bearing off on his turn in order to affirm White should double, but gets the count of Black’s good rolls wrong, finding only 7 rather than 10 successful numbers in 36. At times you wonder whether playing a mean game of bridge really qualified people to be authorities in backgammon.

Perhaps the most vivid omission in the book comes on Problem #9, which is a post-contact race position. White, on roll, leads 69-83 in the race, a whopping 25% lead (though with some wastage). Thorne offers only a rough method of eyeballing the race to reach the conclusion to double (again, no mention of whether Black should take or drop), so this problem strongly suggests that the art of the pip-count had been lost somewhere between the days of Hoyle in the 1800’s, when a valid method of pip-counting was in circulation, and the 1930’s. Of course, it’s not clear what players of the day would have done with a pip-count once they had it, but given the penchant for odds-tables and talk of “mathematical certainties” in many of these books, it seems that these gaming authorities would have been proud to expound on such a tool if they used it.

Like Walling & Hiss, Thorne includes a transcription of a complete back game, but this one is more interesting, with plenty of checker-recirculation. As expected, Thorne is too willing to commit to the all-out back game (simple holding games seem to have been severely undervalued at the time). But the big surprise is that once he achieves a well-timed game and forms the solid 6-5-4 points in his home board, rather than building the prime from the rear, he pops spares up onto the existing prime and seizes his ace-point when the opportunity arises. It’s quite surprising that the preparation / containment phase of the back game would have been so poorly understood, even at the time. You may download a transcription of the game here.

Thorne gets about half of his problems wrong. In many positions offering a choice between a completely safe play and a somewhat risky one, the safe play is generally, and often wrongly favored — without any acknowledgment of the potential benefit of the risky play. The cost of being hit by a joker is often over-weighted, and the necessity of taking a smallish risk to virtually extinguish the opponent’s chances is rarely appreciated. The role of doubling privilege (“cube ownership”) never enters the picture, a step backwards from the Nicholas & Wheaton book, where the privilege was at least specified. One wonders what the other experts of the day thought of these 50 problems, and how far Thorne’s blind spots were shared by the wider competitive community.

Thorne’s “Authorized Rules for 1931” are the ones supplied by Mabardi at the end of 1930, not the Laws that would be published a few weeks later by the New York Racquet and Tennis Club.

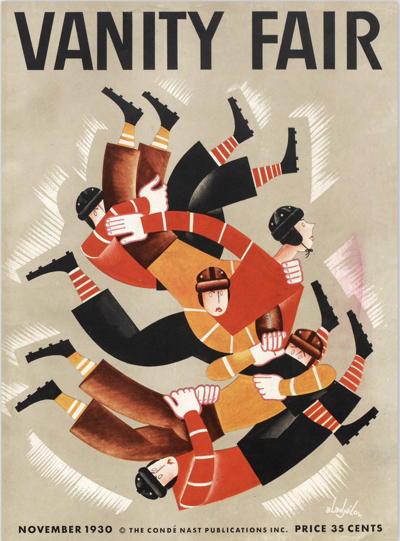

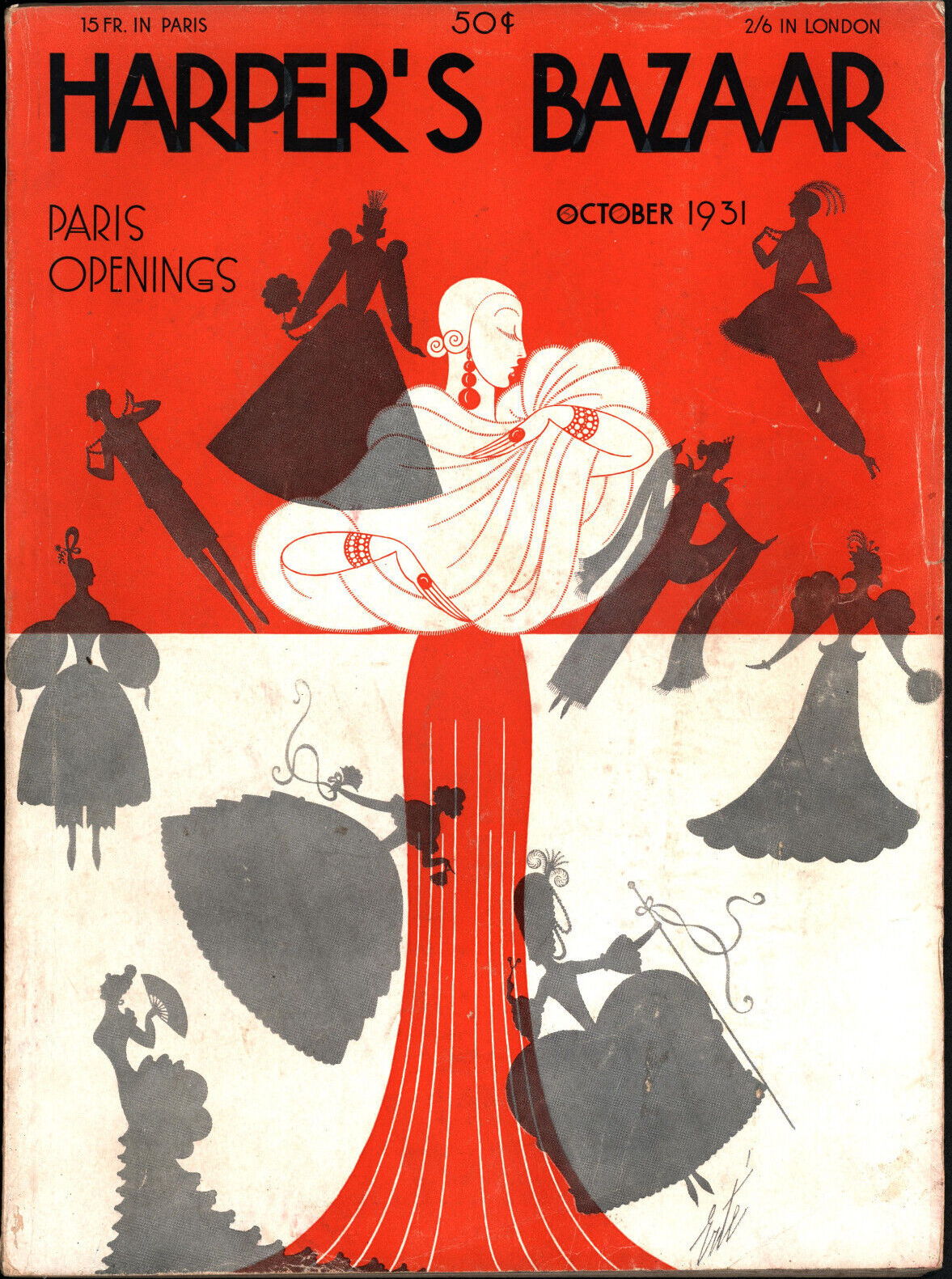

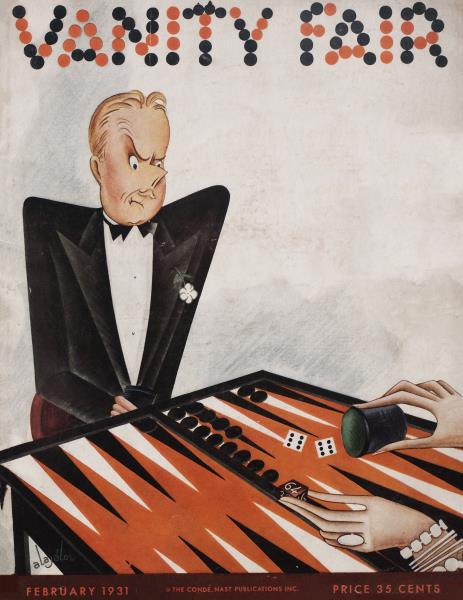

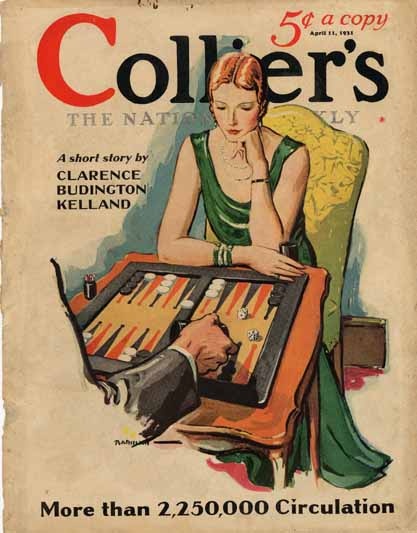

Major Cover Illustrations - (February & April 1931)

Vanity Fair, Feb. 1931

Collier’s Magazine, April 11th, 1931

This pair of vibrant cover illustrations in major publications of the day attest in delightful manner to the raging popularity of backgammon among their readership in early 1931. The February Vanity Fair cover by noted illustrator Constantin Alajalov takes a humorous approach, capturing the buttoned-up annoyance of a club man being bested by his impertinent female opponent in her jazz-age bangles. The cover illustration for Collier’s two months later, by Jay Hyde Barnum seems as though it might have been painted in reply. The perspective is reversed and the man is now rolling, but most strikingly, it’s the tone that has changed, with the female player depicted in the thoughtful pose of an expert. Both are prized issues for backgammon aficionados, and often framed for display.

Both covers also feature doubling devices of recent invention, as discussed on the Early Doublers page elsewhere on this site.

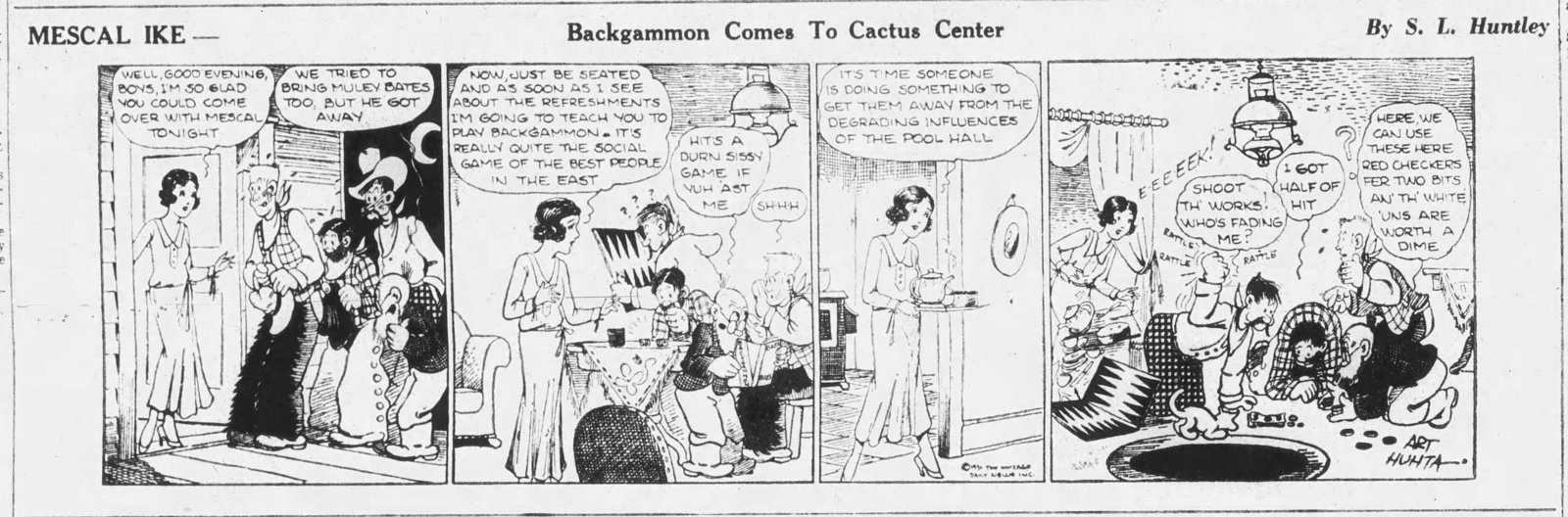

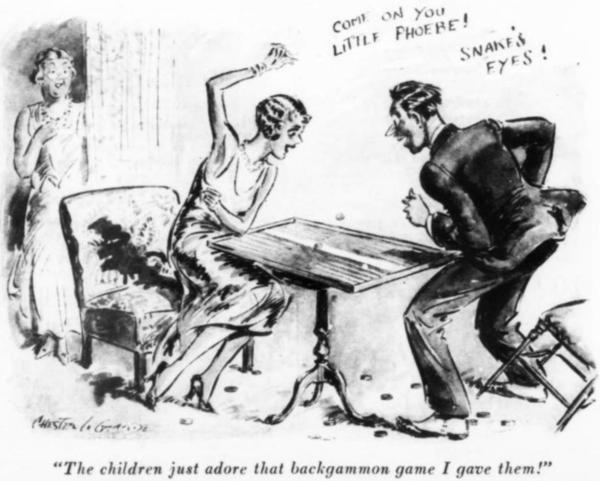

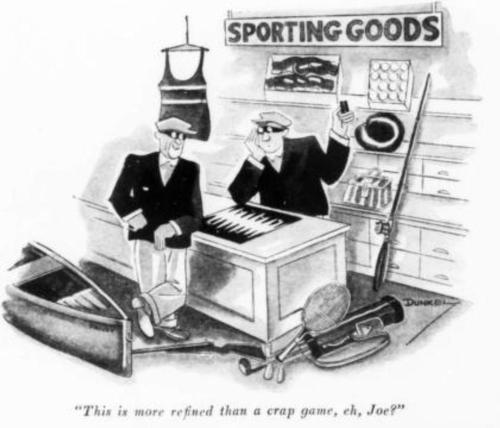

Backgammon & Craps in the Comics - (1930-31)

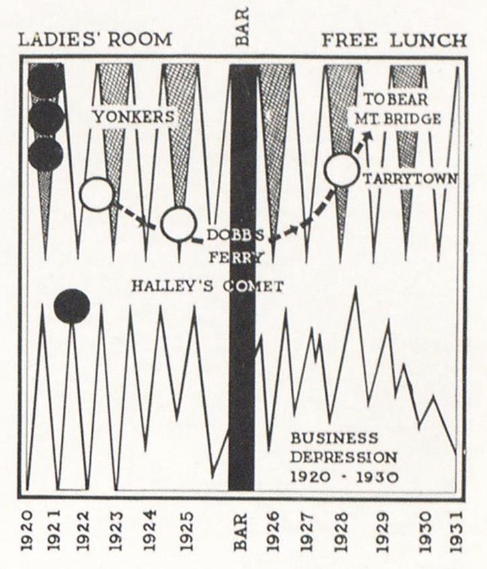

The Herald Statesman, Yonkers, Feb 18, 1931.

Judge, Nov. 29, 1930.

Mescal Ike had a long run from 1926 to 1940, but has long since faded into obscurity. This installment plays on two recurring digs at the backgammon scene. First, the snobby class association with “the best people in the east” and secondly, the somewhat justifiable suspicion that backgammon is really just a glorified game of craps. The cartoon at right plays on the same themes in the opposite direction: the aspiring hostess in Mescal Ike fails to elevate her guests by introducing them to backgammon, while here the elderly matron inadvertently unlocks a gambling fever in her children by introducing them to the game. At bottom left a pair of retail burglars try on society life for size.

Judge, Sept. 19, 1931.

That high-society, big-money backgammon appears not to have attracted police scrutiny while working-class gamblers playing at “street craps” were subject to arrest is the topic of a fourth cartoon on this theme (also from Judge magazine, in the Nov. 1, 1930 issue). Here a group of African-Americans playing craps (a common stereotype of the day) hope to appease a policeman by protesting they’re only playing backgammon — but forgot the board. Although the depiction is far from the cruelest caricatures of the time, I’ve chosen to link to the image here so that viewing it may be the reader’s choice.

The association between backgammon and gambling will continue to be problematic for the game, through the hustling 1970’s and into the 21st century.

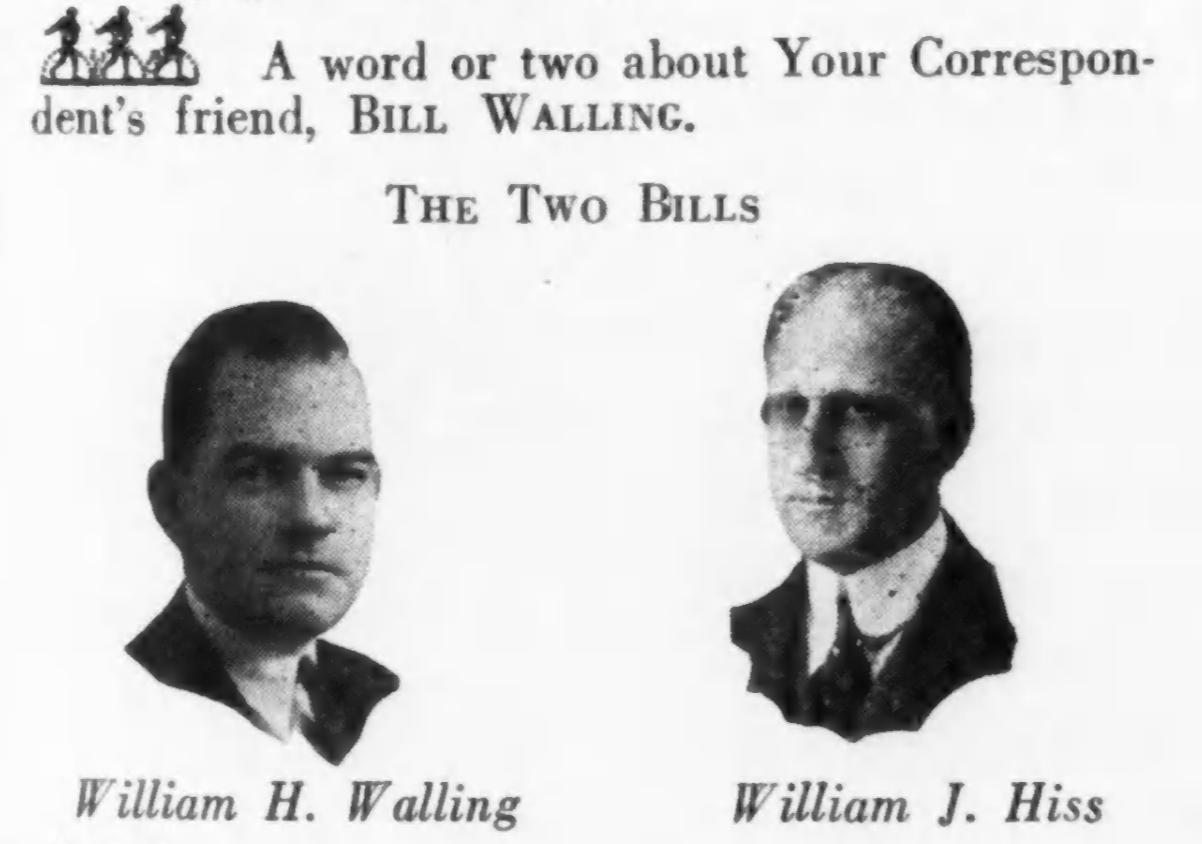

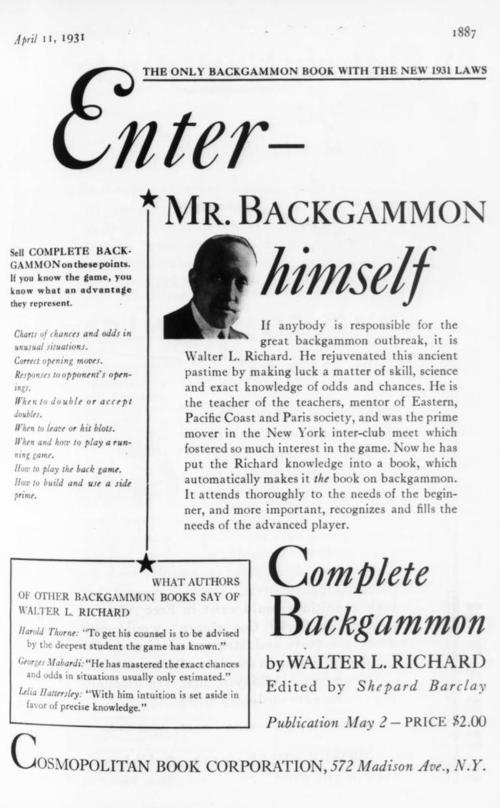

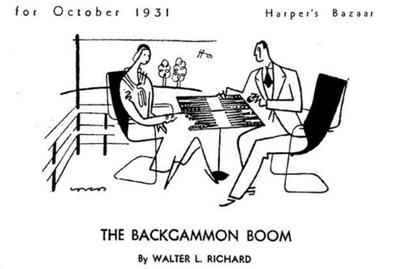

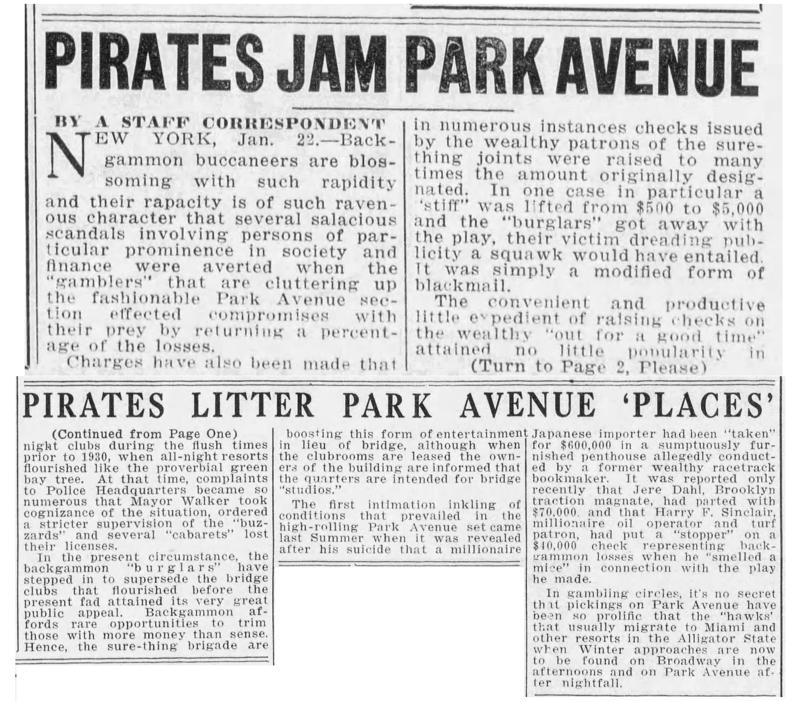

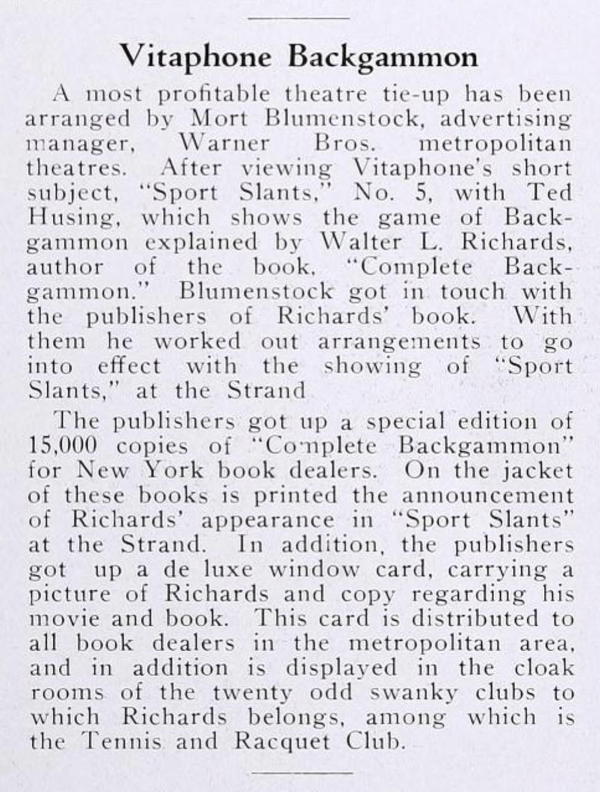

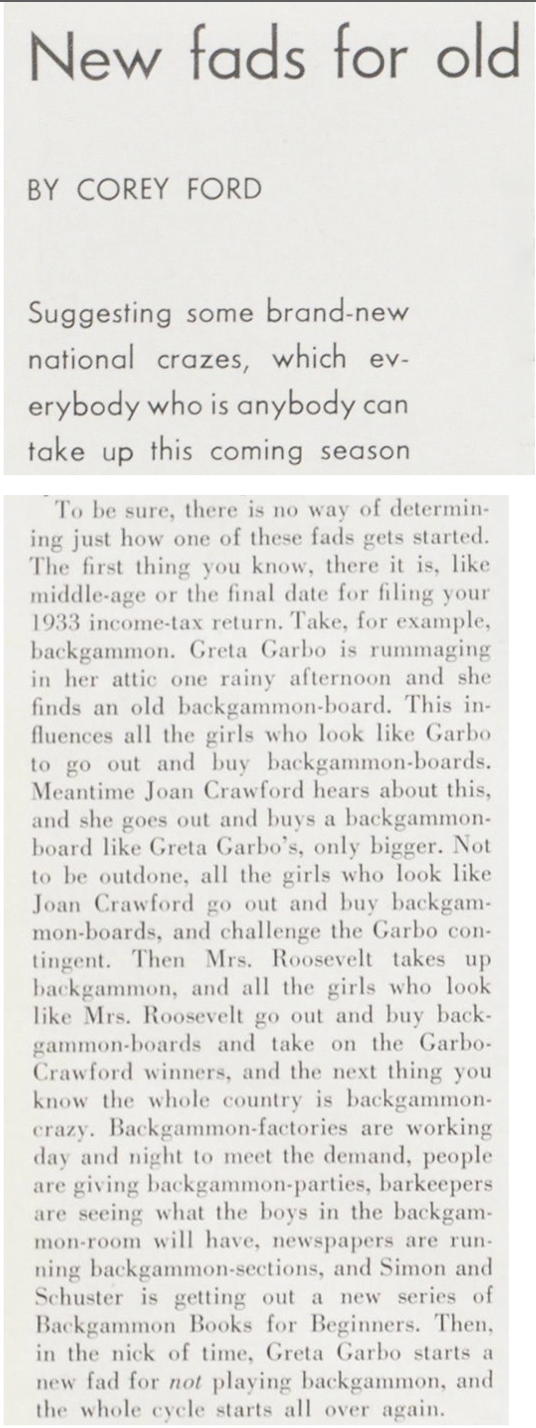

"Backgammon to Lose" (Vanity Fair, Mar. 1931)